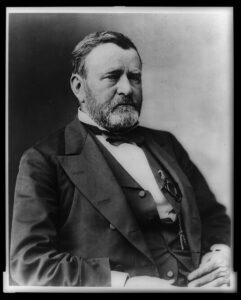

PROVINCETOWN — Preident Ulysses S. Grant’s visit to Cape Cod and the Islands in late August 1874 was more than a mere celebration.

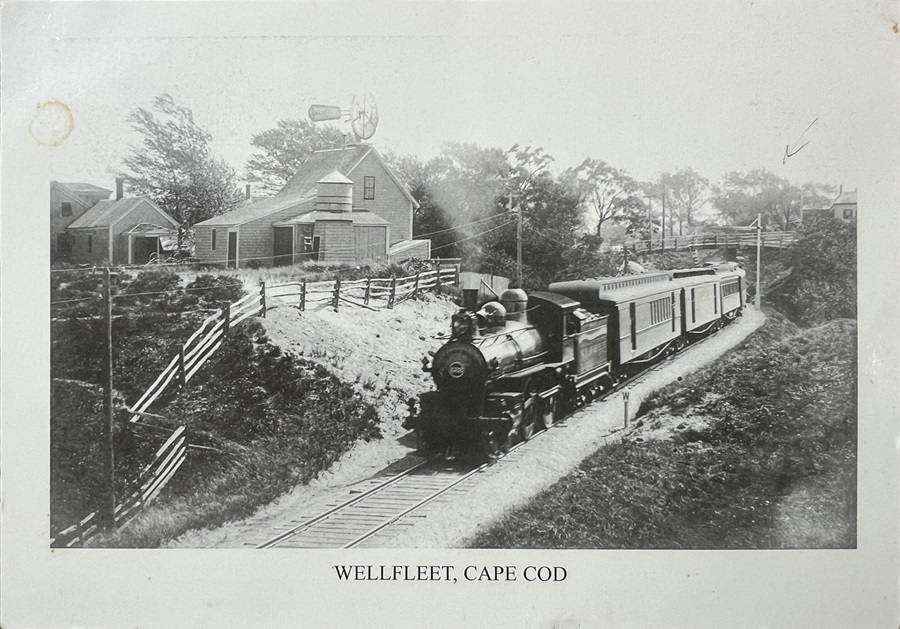

Ostensibly, Grant was here to commemorate the 1873 completion of the Old Colony Railroad line to Provincetown, a milestone that marked the final connection of the Cape to the rest of Massachusetts by rail. But the visit, which was the Cape’s first from a sitting U.S. president, also represented a convergence of Grant’s personal and strategic priorities.

“He was meeting with religious leaders,” said Ryan Semmes, research director of the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library. “He was meeting with business leaders. He was thinking about the economy. He was thinking about America’s place in the world militarily. And he was thinking about the domestic violence occurring in the South during the Reconstruction process.”

Semmes told the Independent that one of Grant’s goals in taking the train to Provincetown was to make a statement about the broader economic challenges facing the nation in 1874.

The Panic of 1873, which was prompted by a stock market crash in Europe and the ensuing mass sale of railroad bonds, had plunged the domestic and European economies into a depression. The New York banking firm and key railroad investor Jay Cooke & Company had gone bankrupt, and soon more than 20 percent of U.S. railroad companies would also declare bankruptcy. But Grant, a firm believer in the transformative power of infrastructure development, saw the expansion of the railroad as a key to recovery, said Semmes.

“He loved the building of railroads,” said Semmes. “He thought that the more connected towns and cities are, the better the economy would be and the quicker the economy could bounce back from the depression.”

Grant had arrived in Martha’s Vineyard on Aug. 27, 1874 to attend the Methodist Camp Meeting. With its blend of outdoor preaching, hymn singing, and communal fellowship it suited Grant’s own nondenominational leanings. Semmes said the meeting imbued the rest of Grant’s visit with a reflective current.

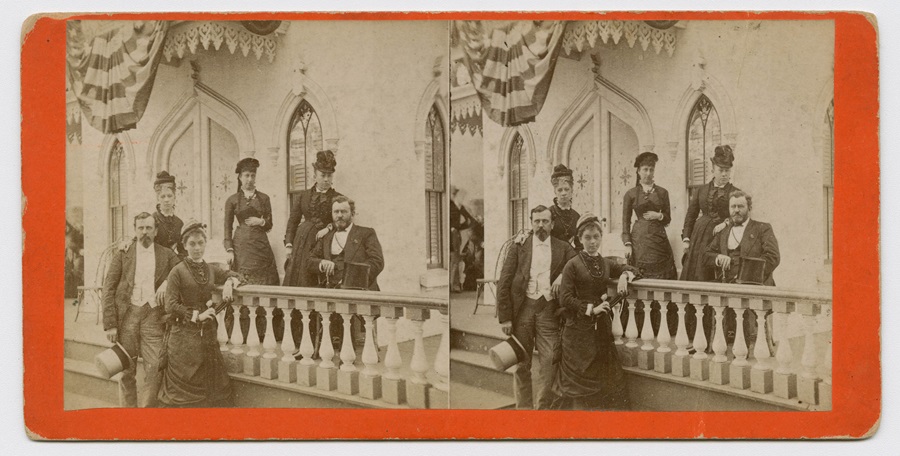

The next day, Grant, his wife, Julia, and a retinue of politicians, captains of industry, military officials, and their families departed Martha’s Vineyard aboard the River Queen. The steamer, which had been a dispatch boat used by Grant during the Civil War, ferried the party on a day trip to Nantucket and then Hyannis, where it arrived around 2 p.m.

From there, they continued by train to the Outer Cape, stopping in Yarmouth, South Dennis, and Harwich and picking up local politicians and businessmen along the way. The president was cheered at each stop. When the entourage arrived in Wellfleet, 400 schoolchildren lined the streets to wave. That stop was “the most successful and happiest of the trip,” according to an article published on Sept. 1, 1874 in the Barnstable Patriot. (The Provincetown Advocate reprinted the Patriot’s story the next day.)

Thomas Newcomb Stone, a local poet, doctor, and state senator, delivered remarks that show how Grant’s Civil War service had become almost mythologized: “We wish only to assure you that, by your service to our country in her hour of need you have endeared your name to the hearts that now beat around you,” the Patriot quoted Stone. “They gladly greet, today, him as President, whom in imagination they have followed from Donelson to Vicksburg, through the Wilderness to Richmond.

“The hardy man of the ocean,” Stone continued, “will oft tell the story of to-day. And when you and I have passed the battle of life, these children will rehearse to another generation this great event of their childhood.”

The Patriot reported that Stone initiated three cheers each for Grant, his wife, and their daughter, Nellie, who lived in England. The train then snaked further up the Outer Cape.

Provincetown greeted Grant with equal enthusiasm. The train pulled into the station at 5:30 p.m. to the sound of the Provincetown Band playing “Hail to the Chief.”

“Flags were displayed from the shipping in the harbor, and from various points in the town, and numerous stores and private residences were profusely decorated, among which was the office of the Provincetown Advocate,” the Patriot noted.

“The scene presented was the most animated anywhere throughout the day,” the Patriot added.

Grant and his party ascended High Pole Hill, where a platform awaited him. James Gifford, proprietor of Gifford House and Pilgrim House, welcomed the president.

“To whatever of enjoyment or interest there may be found on this far-off end of Cape Cod — a place memorable in the history and the institutions of the Pilgrims of the May Flower — during your brief stay, we bid you hearty welcome,” said Gifford, according to David W. Dunlap’s Building Provincetown.

“I regret that my stay in Provincetown cannot be longer,” replied Grant. “I am not unmindful of what has been done by the men of this peninsula for the history of this country, nor of their influence upon the nation.”

Semmes, of the presidential library, told the Independent that the nation’s defense was also on Grant’s mind when he was here. Tensions lingered with Spain following the Virginius incident of 1873, in which Spain seized a ship carrying men and munitions to Cuba and executed 53 crew and passengers, including Americans.

The event highlighted naval vulnerabilities on the East Coast, and people were considering strategic sites to build and moor American naval ships. At the urging of the Cape’s residents, Provincetown Harbor emerged as an option.

“As you have seen the location of Provincetown and the fitness of its Harbour for a great naval Depot you can appreciate the necesity [sic] for its ocupation [sic] for that purpose,” wrote C.C.B. Waterman of Sandwich in a letter to Grant on Aug. 28, 1874.

Provincetown did not become a naval depot, although it did later become a naval base during World War I.

As the day drew to a close, Grant’s train departed Provincetown around 6:45 p.m., making brief stops in Eastham, Orleans, Yarmouth, Barnstable, and Sandwich before arriving in Woods Hole around 10:30 p.m.

In the quiet moments of that August evening, as the train and then the River Queen carried him back to Martha’s Vineyard, one can imagine Grant reflecting on the day’s events, the challenges ahead, and the enduring spirit of the country he had fought to preserve.

The Patriot’s founder, Sylvanus B. Phinney, acknowledged this in his welcome address for Grant in Barnstable, according to the Patriot: “You have had an opportunity to know the barren shores of Cape Cod have been fortunate in rearing men and women, too, who have always been prompt to respond to the call of their country.”