The measured opening of the 115-year-old Herring River dike is front and center in a decades-long restoration project aimed at bringing back some of the Wellfleet estuary’s original tidal flow.

Among the objectives are for the tides to bring in more oxygen and aquatic nutrients for Wellfleet’s shellfish to grow on and to support the river’s namesake herring population, a prime food source for many important ocean fisheries.

But even though this may be the largest salt marsh restoration project on the Eastern seaboard, the current project won’t actually follow the estuary’s original contours and marsh ecology.

I learned this recently while editing an article by David Wright, a keeper of the town’s history and lore, for the Spit ’n’ Chatter Club, a new newsletter to be published by the Wellfleet Oyster Alliance. Wright, who serves as curator of the Wellfleet Historical Society Museum, was writing about how two topics that resonate today — declining fisheries and tourist-chasing mosquito swarms — motivated the construction of the dike back in 1909.

By that time, Wright points out, the marsh here had already been diminished by 100-plus years of ravenous deforestation. There were two culprits, and the first will not surprise you.

Generations of Cape Cod’s European-descended residents had turned much of the peninsula’s hickory, oak, maple, and beech forests into vast grasslands, dotting the landscape with farms. They chopped down the trees to build boats and houses. The latter, lacking adequate insulation, required about 25 cords of wood each year for heating and food preparation. And wood fueled the salt works vital to preserving fish catches for the Cape’s thriving schooner trade.

Without forests to slow runoff, the Herring River estuary was rapidly silting up before Wellfleet’s dike went in. And that process was accelerated by the arrival of the railroad in 1870, its wooden bridges across salt creeks further restricting natural tidal flows.

What settlers and their descendants created here was an open landscape that in places we still see and admire today. When my family first started vacationing in Provincetown in the late 1950s, I fell in love with the Outer Cape’s vast vistas across both the sea and the seemingly endless hills of bearberry and beach grass. They conveyed an unforgettable sense of freedom.

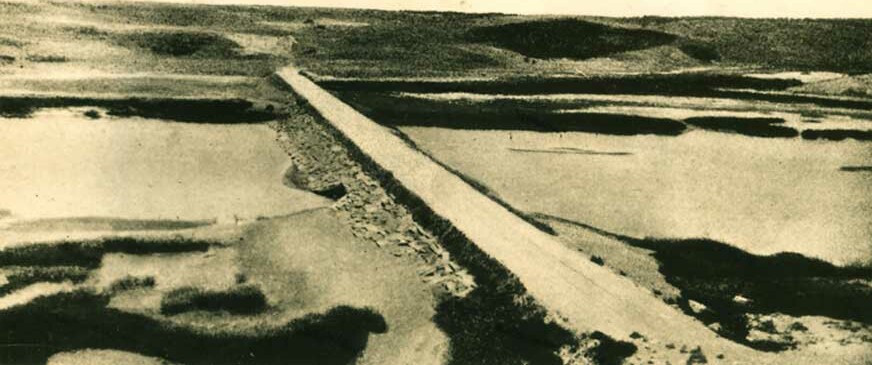

Looking through old photographs taken at the time of the dike’s construction in the Wellfleet Historical Society’s archives (available to anyone at wellfleethistoricalsociety.org), I felt the pull of that breathtaking starkness I first experienced as a boy.

One photo in particular stands out, a north-looking shot taken from the top of a hill on the south side of Gull Pond. In the treeless image, you can see a cluster of ponds — Gull, Higgins, Williams, Herring, and Slough — connected by natural inlets. Those openings, and the strong flow from the Herring River, allowed the ponds to thrive as a prime nursery for herring, whose population was once so thick that a communal netting each spring supported the town’s annual school budget.

It is easy to blame the pre-dike treelessness on the ignorance of our European forebears. But I recently discovered from Charles Mann’s absorbing book 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created that they were lent a huge helping hand by the lowly earthworm.

Mann writes that before the arrival of the first European settlers, no earthworms remained anywhere in temperate North America where glaciers had once covered the land. Native earthworms had disappeared 10,000 years before, during the ice age. Hidden in the root balls of plants brought by the first colonists were the invasive worms that now inhabit virtually every shovelful of dirt we turn over in our gardens.

And this worm, it turns out, may be every bit as devastating to the hardwood forests as man’s prodigious clear-cutting.

The Cape’s ancient hardwood forests relied on the slow decomposition of their leaves and an occasional natural fire to create the soil around them. Their large canopies prevented any thick undergrowth that would provide fuel, so when fires occurred they would quickly race through the forests without causing significant harm.

The clearing of trees and the work of these imported earthworms had the same destructive effect on the forests: worms rapidly devour fallen leaves, creating dirt in the process. They also loosen and aerate the soil, resulting in runoff that augments what’s caused by clear-cutting. Loosened soil exposed to more sunlight from cleared trees led to the appearance of aggressive undergrowth. Fires were no longer the quick, soil-producing events of earlier times but forest-devastating occurrences.

On Cape Cod, the rapidly flourishing worm and man’s aggressive harvesting came into play at the very same time — an unfortunate coincidence for our forests and marshes.

And that takes us back to the story of Wellfleet’s dike building. The nefarious saltwater mosquito had long been part of Cape Cod’s ecology, but the infestation that plagued Wellfleet in the early 1900s and threatened to pull the rug out from under the town’s early efforts to promote tourism no doubt prospered in the slower flows and pooling water created by our rapidly silting creeks.

The flooding of Duck Harbor from storm overwash a few years ago gave Wellfleet and Truro a taste of how standing salt water can affect the mosquito population. We can relate to those earlier townspeople’s readiness to experiment with a dike that promised to halt the insects’ proliferation.

Some ecologists worry about the still-proliferating exotic earthworms, suggesting we should discourage their presence even in our vegetable and flower beds. But Mann points out in 1493 that once new species become established, they are virtually impossible to eradicate.

Humans’ wanderlust, he writes, inevitably results in new versions of ourselves and of our environment. The truth of this is obvious in our own blackberry- and chokecherry-ridden back yards, and in our vegetable gardens, where nearly everything we grow and eat — tomatoes, potatoes, cucumbers, radishes, broccoli, and more — were once exotic species.

A hopeful twist in the saga of the invasive earthworm is that these same animals may very well be an aid in fighting the worst effects of climate change. More than 2.5 trillion tons of carbon are sequestered in soil. And although worms release carbon dioxide as they feed, when the carbon-rich foods they consume are reduced to poop, the hard-packed castings, as they are called, keep much of that carbon trapped in the soil.

The verdict is still out, but there is growing optimism that worms might help us dig out of this proverbial hole. According to the Smithsonian Environmental Research Center, which is currently studying the earthworm problem, “In short, the invading army of earthworms could threaten the planet, just as it threatens individual forests. Or, at this critical moment, they could turn into surprising allies.”