Tucked away beside Highland Links, Truro’s golf course on the bluffs, sits the former turn-of-the-century hotel that’s now the Highland House Museum. There, a repository of local history documenting developments in craft, conflict, and industry lends depth to this place where so many people come every year for leisure.

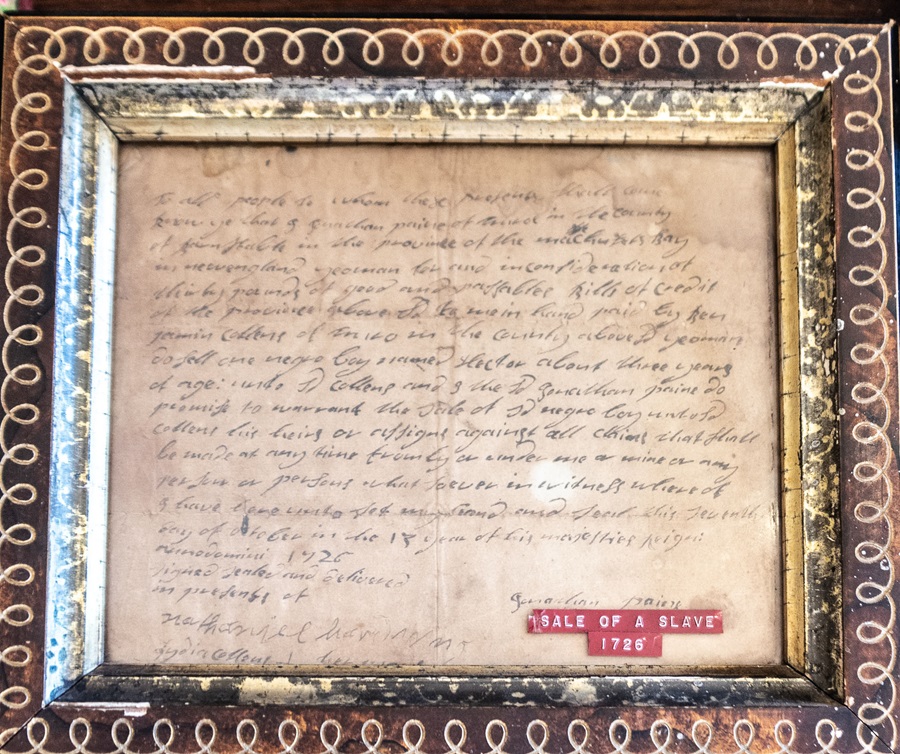

This fall, Steven Philbrick, who lives in Bourne, donated a 1726 bill of sale for a human child, Hector, to the Truro Historical Society.

According to the deed, Hector was sold by Jonathan Paine to Benjamin Collins for “thirty pounds of good or passable bills of credit” — about $7,548 in today’s money. Hector was three years old.

Philbrick is a descendant on his mother’s side of either Collins or Paine, he told the Independent. He remembered the framed document hanging on the wall of his grandparents’ living room in Braintree. When he was young, he said, he did not think about its significance. “It was just another antique.”

But Philbrick, now a member of the Bourne Historical Commission, has become been fascinated with local history. And when he delved into references to Hector, something slid into place about the document on his grandparents’ wall.

That led him to the Truro Historical Society. “It belongs in their collection as part of the history of the town — a part that not too many people know about,” Philbrick said.

Human Chattel

Paine’s sale of Hector to Collins is dated Oct. 7, 1726, and the deed, according to 19th-century historian Shebnah Rich, was “the last probably ever made in Truro for a human chattel.”

According to Rich’s Truro — Cape Cod, Hector’s father, Joe, had also been enslaved by the Paines. Joe asked his master for a wife, and because Paine was “kind-hearted” and “faithful,” Rich wrote, Joe’s request was granted. Hector was born “too soon legally,” though his parents were then married.

Hector wound up on the property of Collins, who was “an owner of meadows, woods, and marsh lands at the Head of the Pamet near the ocean,” according to the 2007 compendium of Cape places, The Names of Cape Cod.

On his hundreds of acres, Collins’s laborers cultivated corn, wheat, oats, and flax. Collins was a “flourishing and quite extensive farmer in those days,” Rich wrote. Hector’s life on the farm, Rich continued, “would seem to us a long, lonely, unloved toilsome life. But he was a faithful servant, a devoted Christian, and seemed content with his lot.”

Hector was baptized in 1747, at age 24, according to multiple accounts. According to The Names of Cape Cod, he “recited his prayers aloud as he worked in the fields.”

Most books that recount Cape Cod’s history dedicate a page or so to Hector, usually framing his story in nonchalant terms.

Poet and scholar Clint Smith points out a parallel in the way histories of plantation life are told in the American South. In How the Word Is Passed, he writes “tours of former slave estates nostalgically center on the architectural merits of the old homes, where you are still more likely to hear stories of how the owners of the land ‘treated their slaves well’ than you are to hear of the experiences of actual enslaved people.”

In his Cape Cod: Its People and Their History, Henry Kittredge wrote in 1930, “Hector, we are told, lived to be an old man and became something of a local celebrity — his name being given to such places as Hector’s Nook and Hector’s Stubble, spots which were once well known to Truro men.”

The historical accounts do not make reference to what made Hector a “local celebrity.”

The Body of Liberties

There were slaves here before Hector’s time. Fifty years before Hector was sold, in July 1676, the indigenous uprising known as King Philip’s War decimated the Narragansett and Wampanoag tribes. Indigenous captives were then divided among colonists “as a kind of reparation,” writes historian Margaret Ellen Newell, author of Brethren by Nature, a book that details a seldom-discussed chapter in American history.

Slavery had been legalized in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1641. Its constitution, the Body of Liberties, permitted the enslavement of “lawful captives in just wars, and such strangers as willingly sell themselves, or are sold to us.”

After the war, the allocation of enslaved labor shaped the colonists’ civic lives: “Local proceedings for dividing captives were complicated pageants that combined bloody vengeance, participatory political bargaining, and hard-headed economic transactions,” Newell writes.

The first ship on what would become the trans-Atlantic slave trade route arrived in Massachusetts Bay in 1638 after departing from the West Indies, according to the daily almanac of state history Mass Moments, a project of the Massachusetts Foundation for the Humanities.

As the Atlantic slave trade developed, Africans were mostly enslaved on plantations in the West Indies. As goods like sugar, molasses, and indigo — all dependent on the labor of enslaved people — became fixtures of the global commodity market, Massachusetts became the first mainland British colony to legalize slavery.

“From 1640 until well after the Revolution,” Kittredge wrote, “slaves were common in all parts of the Old Colony, and if there were fewer on the Cape than elsewhere, it was only because there were fewer rich men or extensive landowners.”

Indentured servitude here often meant laboring as whalers and sailors, according to Helen McNeil-Ashton, vice president of the Truro Historical Society.

For the Record

The exact number of Africans enslaved on Cape Cod is unknown. Aside from Hector, the most referenced enslaved African in Truro was a man referred to only as Pomp, who had been forcibly taken from the Congo by a Truro whaler, according to Paul Schneider’s The Enduring Shore. Pomp hanged himself in Truro in the 1750s, according to Schneider.

“Most Americans really don’t have a good grasp of the reality of our history,” said history teacher and journalist Jim Coogan in a 2022 lecture at the Sandwich Glass Museum about slavery on Cape Cod. “Too often we here in the North feel we have that high moral ground,” Coogan said, citing U.S. history curricula that emphasize the Southern economy’s reliance on enslaved labor.

Of the information out there and the stories we tell ourselves as a result, he added, “What’s left out can be just as important as what has been put in.”

“There is not a central repository of documents about slavery in New England,” writes Jared Ross Hardesty, for the Atlantic Black Box, a nonprofit that involves New Englanders in researching and reckoning with our complicity in colonization and the global economy of enslavement.

“The biggest obstacle to researching slavery in New England is not accessibility,” he writes, “but rather the very nature of the records themselves.”