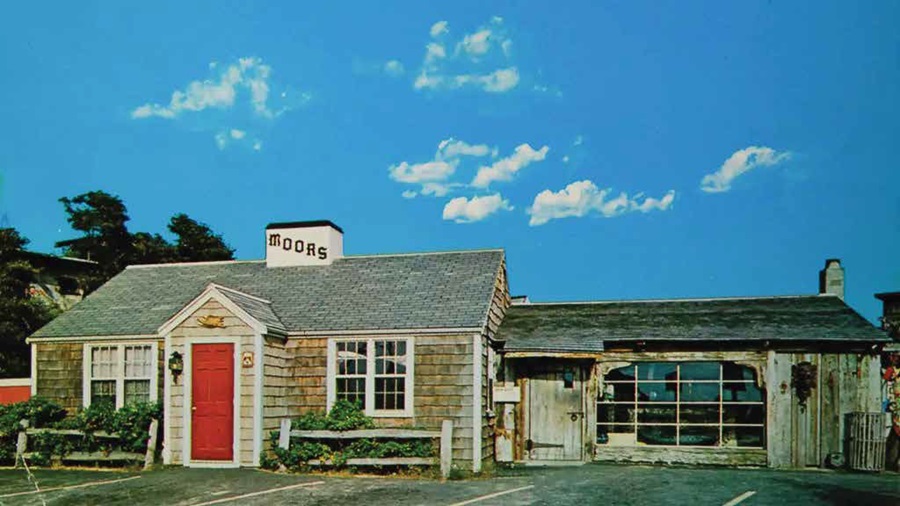

The Moors holds a hallowed place in the history of Provincetown restaurants, even though it has been gone long enough (it closed in 1998) that many latecomers may not know its story. I have lived in this town well over 50 years and have only the dimmest recall of it. I have always been an East End guy. The Moors could not be any further west in town, and early on I had little money for eating at restaurants.

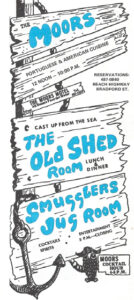

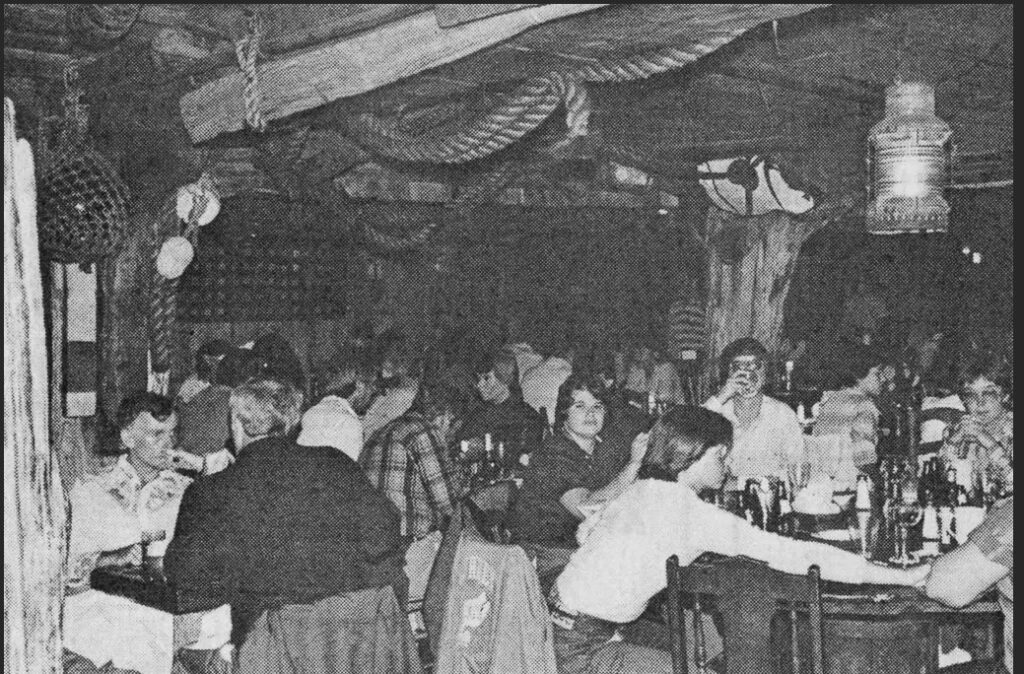

What I do remember is a large, dark place — “more than a bit raffish,” writes David Dunlap in Building Provincetown — with Lenny Grandchamp at the piano, and a resident owl. And then a devastating fire.

What follows here is a powerful story about an incredible man, Maline Costa, the creator of the Moors, told by his sons, Mylan and William. Through their words, we learn of the boundless energy and perseverance of the man (and the vision of his first wife), his carpentry skills (he seems to have built most of the important buildings in town), and the esteem in which he was held by the people of Provincetown.

Sal Del Deo says of Maline Costa: “He was the most loved man in town.” His story reminds us what a cohesive community Provincetown was in those days — the fire was in 1956. It is a story of people coming together to help one of their own. I hope we would do the same today.

Maline Costa was the son of Ginevieva Periado from São Jorge, the Azores and Manuel N. Costa from São Miguel. His father was among 20 men who were tragically lost at sea aboard the Grand Banks schooner Cora S. McKay off Newfoundland on Sept. 12, 1900. It was the worst maritime disaster of the new century for the tight knit community of Provincetown. Ginevieva Costa was left a widowed mother with several children to support, resorting at one point to hiding three-year-old Maline and his brother under the stairwell of their home in Provincetown for fear that the welfare department would take them away.

Maline left school as a young boy to help support the family. In the mornings he delivered milk for Horton’s dairy and afternoons he went to the wharf to ask for fish as the boats were unloading. No one was ever denied fish, especially widows and orphaned children. He shoveled coal for his neighbors, who let him take home the dust and smaller chunks at the bottom of the delivery wagon. “He knew what it was to scrape for heat and food,” his sister Janet said.

Maline left Provincetown at the age of 14 or 15 to learn the carpenter’s trade in Cambridge. Always watching and learning from the master carpenters, he taught himself to read blueprints. He became a master carpenter in his own right; looked up to by the younger men just entering the trade. A special kindness was extended when he took on a young Dick Henrique, a Pearl Street neighbor, as an apprentice who like Maline had been forced by circumstances to start working while just a boy to support his family.

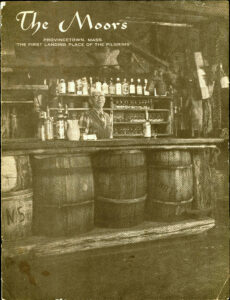

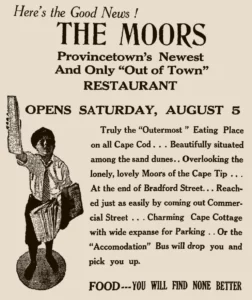

Maline married Vivian Marshall of Provincetown in 1921 and together they started a small restaurant called “The Shed” in the center of town. He decorated the restaurant with relics he had collected over time from the old days of wooden ships and canvas sails, making it a veritable museum of whaling artifacts. They did very well, and the place was beginning to feel too small, so Vivian, as a surprise for Maline, bought a plot of land at the far west end of Bradford Street for $1,200. Vivian was not only a good cook, she had good business sense and knew that an opportunity lay in the newly opened road out to New Beach (Herring Cove), which was previously accessible only on foot, over sand.

Maline was sensitive to others’ needs from personal experience of hard times. He was not above giving a free meal to someone and slipping a few dollars in their pocket after he fed them. His generosity would be repaid in full not too many years later. In 1939 Maline dismantled the Shed stick by stick and rebuilt its replica, along with all the treasured marine memorabilia, at the new location. Over time, the restaurant grew, built with wood Maline found combing the back shore in the trusty old Jeep he called “Hi Ho Silva.” He completed building the kitchen and a traditional dining room.

At the beginning of World War II business declined, there were blackouts, and the Navy took over part of the restaurant as a storage facility used by the Coast Guard at Wood End. Maline needed to keep food on the table for his family, so he went to work as a longshoreman at Castle Island in Boston during the war. He returned home whenever he could, picking up his favorite pastime scavenging the beaches for artifacts to be used as decor at the Moors.

When the War ended and the Moors had been completed, business picked up in the spring and summer, but the winters were difficult. The postwar building boom was taking hold, and his carpentry skills were in high demand. The landscape of Beach Point was being transformed and Maline and his crew were a part of it. Over a period of years, he built Kalmar Village, owned by Alton Ramey, the Breakwater Motel, owned by John Van Arsdale, Pilgrim Colony, owned by John Williams, and, in town, Lands End Marine Supply, owned by Joseph Macara, to name a few. He also tore down the West End Cold Storage practically single-handedly.

Many Provincetown men learned the trade while working with Maline — John Mendes, Peter Maruck, Russell Perry, Basil Santos, Matt Costa, Don Langely, Tom Pires, “Tiny” Rivard, and Dick Henrique, among others. In 1950, Maline built Nelson’s Market on the corner of Conwell and Bradford Streets for Clarence Nelson (Far Land today). This was an important building because Maline was the first contractor in Provincetown to use plywood as a building material. Nelson’s Market was the first building in Provincetown to be built with it.

Maline’s wife, Vivian, passed away in 1951. Several years later he married Naomi Dayton, as able a businesswoman was Vivian. The Moors continued to flourish and Maline built a group of stores in the parking lot, renting them out to various craftspeople. Clifton Perry, a very good carpenter in his own right, operated a woodworking shop there. Maline also had the dining room decorated by Peter Hunt, the famous owner of Peasant Village in Provincetown, but few ever had the pleasure of seeing it because of what happened next.

On the morning of May 28, 1956, a devastating fire leveled the restaurant. Maline had just finished renovations and improvements to the kitchen, getting ready for the new season. The fire chief said the fire was due to a defective furnace, but Maline said it was turned off when he left that night. Interestingly enough, two other fires had taken place in that area in a period of about two weeks at the “Castle,” home of Dr. and Mrs. Carl Murchison, and another house close by.

The town was shocked when it heard of the fire that burned the Moors to the ground and rallied around Maline, promising to get him back in business for the summer. Dozens of Maline’s friends and neighbors worked night after night by the light thrown from parked cars, after working their own full days. They rebuilt the Moors in 30 days, just in time for the start of the busy summer season.

Almost all of Maline’s treasured nautical artifacts were consumed in the fire. Phil Bayonne, the empresario of Weathering Heights, hosted a benefit for the Moors. The whole town was invited and the price of admission was a piece of nautical memorabilia, an old oar, buoy, or hank of line.

The Moors was noted for its Portuguese specialties on the menu and many people remember the famous Moors “happy hour” in the late ’50s and early ’60s. It was a raucous drink and song fest every afternoon as people walked into town from the beach. Maline never participated in the fun at happy hour. Instead, he remained content behind the bar with his pet owl, “Scooter,” quietly enjoying what he had created.

Excerpted from the Seamen’s Bank Annual Report 2023, reprinted with permission. With thanks also to David W. Dunlap/The Provincetown Encyclopedia for photo research.