EASTHAM — Resting beneath the National Seashore’s Salt Pond Visitor Center is what used to be the ninth hole of the Cedar Bank Links golf course. The Eastham Town Hall sits atop the 12th hole, and the other 16 have been buried under the dunes and marshes rimming the pond and the Nauset Inlet. Willow Shire, who owns a place neighboring the old, white-chimneyed clubhouse, points out traces of bunkers, now carpeted by grasses and shrubs. The concrete rollers that once smoothed the greens remain in the high grass.

Before it was sold to the Seashore in 1959, Cedar Links belonged to its creator, Quincy Adams Shaw, a descendant of President John Adams. Shaw had spent a decade in McLean Hospital near Boston after suffering a breakdown in 1915, and when he was discharged, his doctors suggested he find a hobby to “ease his shattered nerves,” the Cape Cod Voice reported in 2006.

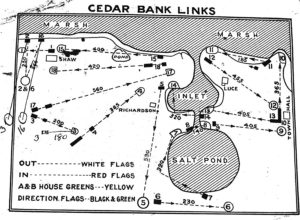

Shaw took their advice and set his sights on golf. He did not begin the way most players do. He started, in 1925, by buying up parcels of land in Eastham. With the help of local farmer Dan Sparrow and his trusty horse, Jerry, they flattened turnip and asparagus fields into fairways. Jerry pulled a scoop shovel, plowing bunkers. By 1928, Shaw and his crew had chiseled a 72-par, 18-hole course from the marshland. It quickly earned a reputation as notoriously challenging, bedeviling even the sport’s heaviest hitters.

Francis Ouimet, a breakout star, was a Cedar Links regular. He started his career as a caddie, but in 1913, he swept the U.S. Open, beating the world’s best as an amateur. At Cedar Links, Ouimet managed a 75.

One weekend, Bobby Jones joined Ouimet for a friendly game at the course. A four-time U.S. Open champ, having won nine other major tournaments, Jones is considered one of the best golfers of all time. That weekend in 1931, he shot a one-over-par 73, the best score Cedar Links had ever seen.

Traps spanned a smorgasbord of ecosystems: marshes, swamps, the salt pond, and tidal pools. Swept off course by a steady sea breeze, golf balls — “thousands” of them, estimated the caddie Don Sparrow, who was Dan Sparrow’s son — careened into these bodies of water. Caddies would roll up their pants and wade in. “The only way to find the balls was to go in and feel around with your feet on the mucky bottom,” Don Sparrow said in a 1990 oral history at the Eastham Historical Society.

The 17th hole was particularly “fiendish,” wrote Sparrow in a 1981 article for the Cape Codder. The tee location required driving across the inlet. The fairway on the other side twisted to the right, flanked by salt marsh. Players had to load their clubs, caddies, and themselves aboard a wooden barge, then tug themselves across the water with a rope and pulley system. Soaked shoes were a foregone conclusion. Golf clubs that teetered into the salt water were fished out.

Conservative players, according to Sparrow, tackled the 17th in piecemeal fashion: clear the inlet first, then wind around the fairway. But the skillful, ambitious, or foolhardy tried to cut the corner, shooting a hypotenuse across the water and aiming directly for the green. “Too short, or to the left or the right, and the player was in the marshes,” Sparrow recalled. “Too far, and the ball was in a mixture of bayberry bushes, blackberry vines, and beach grass.”

The course was maddening, but the caddies found a perk in this. Don Sparrow had taken up caddying in his teens. Over time, he noticed that most of his coworkers ended up with their own “sets” of clubs, consisting of castoffs from disgruntled players. “I’ve never hit a good shot with the damn thing,” one of them remarked to him. “If this drive is no good, you can have it.”

“His ball hooked badly,” Sparrow recounted in his memoir, Growing Up on Cape Cod. “And, without a word, he threw the club at me.”

Cedar Links was also the site of Quincy Adams Shaw’s Labor Day clambakes, with lobsters and steamers cooked over coals under a canvas tarp. “They were rather rowdy parties,” Sparrow said in his oral history. “A fitting end to the summer.”

The parties were exclusive, too — much to the frustration of a former speaker of the Mass. House, who didn’t receive an invitation. One year, the story goes, he decided to crash the clambake in spectacular fashion. He threw on a loincloth, covered himself in what he imagined as tribal paint, and paddled in by canoe, in a mocking depiction of the first encounter myth. Shaw and his guests responded by flinging rocks.

Nature has since reclaimed Cedar Links, but Mark McGrath, a hike leader and historian, has sought to preserve its tales. The area first captivated him when a guide on a Salt Pond trail mentioned Ouimet and Jones. “I thought, ‘Hey, this isn’t just a dinky, little course,’ ” McGrath said. He connected with Bill Burke, the Seashore historian, who referred him to Sparrow.

Sparrow had left caddying to attend Phillips Exeter. A Harvard acceptance followed, and later, he received a master’s in chemical engineering from MIT. He retired in Eastham, having written five books.

When McGrath first met him, Sparrow was 90, and they struck up a friendship, sipping bourbon and swapping stories. Before Sparrow died in 2014 at age 92, McGrath gathered some friends to play at Cedar Links, even though it had been dormant for nearly 50 years.

They met bright and early, around 7 a.m., at the ninth hole — now the far end of the Visitor Center’s parking lot — but seeing cars already parked there, decided to postpone, setting an even earlier tee time for the next day. Seeing things were all clear, McGrath said, “We hit our drives up the fairway,” even though it was now made of asphalt.

Staff reporter Cam Blair contributed research for this article.