EASTHAM — As the nights chill, the leaves fall, and the holidays approach, our thoughts turn to, yes, the turnip — that ancient crucifer that has, for too long, been relegated to the lowly status of livestock feed and staple for the poor. But don’t tell that to the folks in Eastham who have elevated their local turnip to celebrity status, honoring the deliciously sweet, white-fleshed, open-pollinated heirloom with its own festival.

Eastham has seen its share of change over the last century, but one thing that hasn’t changed is the Eastham turnip. Because its single seed line “breeds true,” producing offspring of the same variety, today’s turnip has inherited all the traits of its parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents. If our own ancestors could return for a family supper, their Eastham turnip would taste just the way they remember it.

The origin of Eastham turnips seems to be another Cape Cod mystery. As early as 1875, Eastham, the most agricultural of the Outer Cape towns, was the third largest producer of turnips in Barnstable County. In January 1884, the Barnstable Patriot reported that, during one week, 1,200 bushels — a bushel weighing about 55 pounds — had been shipped by train from Eastham to Boston. In 1895 the Yarmouth Register noted that J.B. Steele and George M. Harding were expecting to have the finest lot of turnips — 3,000 bushels — of any farm in Eastham. By 1905, Eastham ranked first in the county for turnip production.

A 1911 story in the Sandwich Observer mused that the “happy and contented community” of Eastham, with a population of 518, was running smoothly on a total appropriation of only $3,470, thanks in part to its asparagus crop and its famous Eastham white turnips.

How to explain the success and magical flavor of these tandem crops, asparagus — known as “grass” — picked in the spring, and turnips pulled in the fall? Was it the quality of Eastham’s sand, said to be particularly suited for both crops, and, perhaps, some peculiarity of the Cape atmosphere? By the 1920s, hundreds of acres were devoted to the two crops and by the early 1930s, the heyday of turnip production, upward of 50,000 bushels of turnips were marketed annually, a portion of the harvest often buried in pits and covered with seaweed to wait for higher prices in the spring.

If the Eastham turnip can boast a resilient ancestral line, so could one of Eastham’s turnip-growing families, the Bracketts, whose turnips are said to be the progenitors of today’s Eastham root. Through the marriage of William Brackett to Sarah Hopkins, the family was descended from Mayflower passenger Stephen Hopkins. In 1805, William and Sarah’s son, Samuel, married Mercy Cobb, and in 1808 the first of their 11 children, Elkanah — named for Mercy’s father — was born in Wellfleet. A mariner in his early years, Elkanah eventually came ashore and by 1880 was farming 16 acres of sandy Eastham soil.

Married three times, Elkanah Cobb Brackett rests with his wives, Sally Holbrook, Paulina Cole, and Achsah Snow Crosby, and other family members in Eastham’s Congregational and Soldiers Cemetery, a small burial ground with a rural character located along Route 6, next to Evergreen Cemetery. The cemetery takes its name from its association with the third Congregational meetinghouse, which was built on the site in 1829 and razed after 1864 when the Congregationalists disbanded, and from the Civil War obelisk presented by the Ladies Soldiers Aid Society of Eastham. Though not off the beaten path, the cemetery seems a little forgotten, undisturbed, scattered with prickly pear cactus.

The Brackett cemetery plot tells a sorrowful tale. Sally Holbrook died in 1834 at age 24, leaving three very young children for their father to care for. A year after Sally’s death, Elkanah married Paulina Cole, and in 1836 and 1838 the first two of their six children were born. But in those same years, his daughters, Sarah and Lucy, from his marriage to Sally died, both before their fifth birthdays. Later in 1838, the first-born son of Elkanah and Paulina, also named Elkanah, died at age two, and in 1843 William H. Brackett, the last surviving child of Elkanah and Sally, was lost at sea at age 14. Sally’s three children share her headstone.

After the death of Paulina in 1860, Elkanah married Achsah Snow Crosby, with whom he had three children. Richard, the first born, died in 1862 at six months and is buried with his father, though their toppled headstone, sunken in the sandy soil, is difficult to decipher. Its base remains in place and, perhaps, one day the stone could be restored.

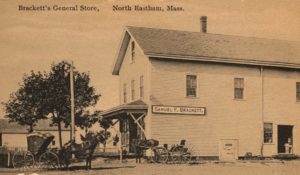

Sons George Pierson (1863-1946) and Samuel Francis (1864-1948) inherited their father’s homestead and would become Eastham’s legendary turnip and asparagus growers, farming 48 acres, a portion of which is now the Seamen’s Bank at Brackett Farm on Route 6. On a knoll adjacent to the bank’s parking area, bronze tablets — installed on a polished stone elegantly etched with turnip and asparagus designs — pay tribute to the family. For decades, until it closed in the mid-1930s, the brothers also owned Brackett’s General Store.

The Depression years took a toll on Eastham’s turnip farms, but the family tradition continued with George’s son, Raymond Vaughn Brackett (1893-1982), and later with Art Nickerson (1915-2008), who, as a boy, had farmed with Raymond Brackett and whose father, George Nickerson, was also a longtime turnip grower. Various career paths took Art Nickerson away from Eastham, but he returned in the early 1950s, was given stewardship of Raymond Brackett’s turnip seeds, and, despite the vagaries of farming and modern life, managed to keep alive what a reporter in 1923 had called the “justly inherited name and fame” of Eastham’s heirloom.