On a July day precisely 150 years ago, a Wellfleet sea captain unloaded a cargo that would shape the course of history. By bringing the first bananas into the U.S., Lorenzo Dow Baker laid the foundation for the United Fruit Company, legendary maker of fortunes, fortress of political power, icon of global capitalism, strangler of nations, and vivid demon in Latin American cosmology.

United Fruit was a corporate juggernaut that swept nations before its whirlwind. For his role in creating it, Baker lays fair claim to being the most potent figure ever to emerge from our sandy soil. His story, more than that of any other individual, connects the Outer Cape with the glory and tragedy of the American epic.

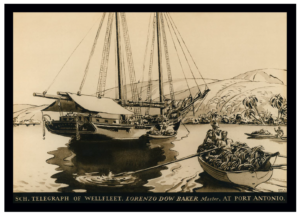

Baker was born in 1840 at Bound Brook Island, then a bayside fishing village near the Truro town line. The youngest of eight siblings, he went to sea at 10 and was a captain by 20. A few years later he bought the schooner Telegraph, by one account “a pudgy, undersize all-wood two-master,” and began ferrying goods between New England and points south.

In June 1870, Baker brought a party of gold prospectors and their equipment to Venezuela. On the homeward trip he put in for repairs at Port Antonio, Jamaica. There he cast about for a moneymaking cargo to carry home. The port master suggested an odd-shaped local fruit that was then unknown in the United States. Baker decided to take a chance. He sent word out to the countryside that he was buying, and departed with 608 bunches of green bananas.

After nearly two weeks at sea, Baker’s bananas began to ripen. He made for the nearest port, which turned out to be Jersey City. A wholesale grocer bought all 608 bunches, bringing Baker a tidy profit. He immediately sailed back to Port Antonio to pick up a second load. This time he packed 1,408 bunches of bananas onto the Telegraph and made for Boston. Days after arriving, he formed a fateful partnership.

Baker’s new partner, Andrew Preston, was an ambitious clerk at the produce firm that bought his cargo of bananas. The two of them rounded up enough investors to capitalize an import firm they called the Boston Fruit Company. It became highly successful. Baker spent much of his time overseeing operations in Jamaica, and directed the company’s expansion into Cuba and the Dominican Republic. In 1899, after absorbing properties in Central America, the company was rechristened United Fruit. Today it is Chiquita Brands International, still dominant in the global banana trade.

Jamaica was Baker’s great love. He endowed schools, hospitals, and churches, “adopted” several local boys and supported them throughout their lives, and built a grand seaside hotel that provided jobs while attracting tourists to Port Antonio for the first time.

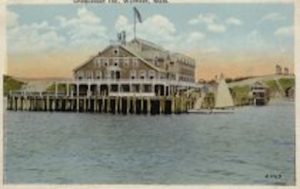

Baker was a tourism pioneer in Wellfleet as well. His 62-room Chequesset Inn was built on a wharf near today’s Mayo Beach and offered luxuries like telephones and hot baths. He brought Jamaicans to work there alongside local people — great-grandparents, perhaps, of those now living on the Outer Cape. The hotel finally succumbed to ice damage in 1934.

Banana Republics

By that time, United Fruit was exercising the ruthless power that led it to become known as el pulpo, the octopus that squeezed the lifeblood out of Latin American nations and turned them into servile “banana republics.” In 1911 United Fruit organized the overthrow of a nationalist government in Honduras. In 1928 striking United Fruit workers were massacred in Colombia. During the 1950s, the company worked with the CIA to undermine democracy in Guatemala.

Because of this bloody history, United Fruit became a cultural archetype in Latin America. Pablo Neruda wrote that when a United Fruit overseer looked at a worker, he saw “a thing without name, a discarded number, a bunch of rotten fruit thrown on the garbage heap.” One of the greatest 20th-century works of political art, Diego Rivera’s Glorious Victory, is a passionate protest against the company’s exploitation of Guatemala.

Lorenzo Dow Baker died in 1908. He never saw his company commit the acts that turned it into a caricature of transnational corporate villainy. Would he have approved?

Baker was compassionate and pious, revered in Wellfleet as in Port Antonio. He treated his seamen well, supported charities, and kept the Sabbath. Perhaps his loving spirit would have rebelled against the campaigns of corporate rapine that United Fruit waged after his passing. Or perhaps the opposite: accustomed to ruling over natives in Jamaica, would he have consented to repressing defiant Hondurans, Colombians, and Guatemalans? We can only guess.

The Wellfleet Historical Society and Museum holds a delightful collection of photos and artifacts connected to Baker. Documents that illuminate his astonishing life fill 11 boxes in an archive at Cape Cod Community College. An ideal place to reflect on his legacy would be in or near the spacious home where, when not in the tropics, he lived with his wife and family. It still stands at 1515 Railroad Avenue in Wellfleet, stately and for sale. His childhood home also survives.

Lorenzo Dow Baker rose from windswept Bound Brook to wield power that rivaled that of generals and presidents. He was a beloved benefactor who helped conceive and direct an enterprise that, after his death, deeply scarred Latin America. The bananas he offloaded 150 years ago secured his place in the history of Wellfleet and the Western Hemisphere.