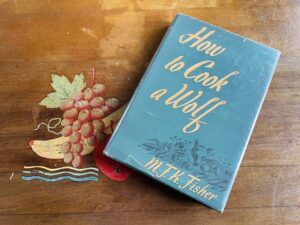

M.F.K. Fisher’s How to Cook a Wolf was published in 1942. This is not a cookbook nor even a memoir, really, but rather a guidebook to feeding each other and oneself with defiance, about the pains of wartime that reach well beyond the battlefield, and about staring down a bare cupboard with creativity rather than despair.

I think of this as one of my least favorite of Fisher’s works, not because I find it to be any less compelling than her other books (in truth, this is where she really harnesses and crystallizes her belief that it’s the great duty of our lives to live and eat as well as we possibly can under our circumstances and to help others do the same) but because this is hard stuff to look at head-on.

The book was written in response to the broad rationing of commodities during World War II, with the specter of the first Great War very much still present, under threat of air raids, blackouts, and the possibility that you and your family might need to take to a bunker to stay alive on whatever cans and packets of food you’d assembled there. There is a particularly bleak section that always gets mentioned in discussions of this book about her recipe for “Sludge” — a purely functional mix of the cheapest available proteins, starches, and vitamins. It’s survival food. It is not romanticized, and it should not be replicated unless things are very dire.

Most of us would much rather read about Fisher traveling through France and being taken on excursions by kindly maitres d’hotel or eating sun-warmed apricots in the orchards of her California childhood. But even I have to recognize the obvious: duality truly being one of our most reliable moderators, those sweetnesses would surely not glisten as jubilantly without their difficult and bitter counterparts. And so, we have to have both.

The titular Wolf is never given an exact identity, although it is allowed the personification of sniffing through the keyhole, stalking past the doorway, clawing under the threshold. The Wolf is another Great Depression. The Wolf is the draft. The Wolf is illness, poverty, anxiety. While we are not technically at war today, the Wolf doesn’t feel particularly far behind us.

I started to think, with food prices skyrocketing like cortisol during a panic attack, that we might be about to need How to Cook a Wolf more than we have since the war that inspired it ended. At the least, I knew that I needed to re-read it for the first time in probably 15 years.

In the chapter “How to Be Sage Without Hemlock,” Fisher addresses the importance of listening to the urges of our natural hungers. She wants us to remember that it’s more important to have a balanced day with a modicum of novelty, eating what you’re hungry for, than to commit to “one routine meal after another, three times a day and every day, year after year, in the earnest hope that you are being a good provider.” Eggs were not the lightning rod for discontent in Fisher’s time that they are these days, but this chapter shores up one of my longest-held beliefs: the only requirements for deeming something a breakfast food are a) that it is food and b) that you want to eat it for breakfast.

One of my favorite chapters is called “How to Be a Wise Man.” It deals with how to feed and by extension love and raise our kids when the Wolf is at the door. This, again, comes down to agency, choice, and instinct. Her point is that when we are allowed to practice making choices for ourselves, we forge pathways in our brains that will not only help us feed ourselves well as we grow but also be better able to weigh our own values, both sensual and spiritual. Fisher notes in a 1951 amended edition with her commentary included that she feels even more strongly than she had in 1942 that one of the most important things about a child’s growth is respect for food, especially in times of austerity, because it gives us an opportunity to form memories around it.

“It was a nice piece of toast with butter on it,” she says, in a moment that perfectly distills why I love her writing. “You sat in the sun under the pantry window, and the little boy gave you a bite, and for both of you the smell of nasturtiums warming in the April air would be mixed forever with the savor between your teeth of melted butter and toasted bread, and the knowledge that although there might not be any more, you had shared that piece with full consciousness on both sides, instead of a shy awkward pretense of not being hungry.”

The chapter immediately following this one, “How to Lure the Wolf,” is a painfully outmoded and bizarrely out of character guide to keeping oneself attractive and well-moisturized in the kitchen, even going so far as to recommend keeping a small mirror and some lipstick next to the sink, in case your guests should arrive before you’ve had time to fix your face, and using the leftover cooking grease to moisturize your hands. (OK girl, whatever you say.)

There is talk of drinking, of course, with special attention paid to getting the most bang for your buck, and also how to tell whether you’re indulging too much. And in “How Not to Be an Earthworm,” she finally tackles the dreaded task of recommendations for making your time in the bunker as delicious and fortifying as possible. It includes reminders that meat in tins will be extra salty and how to account for it, several insistences on the steadying properties of tomato juice, and an admission that even fake cheese in a jar performs the task of making people feel hungry. She jokes in her 1951 commentary that this section is about as useful and relevant as “a treatise on how to treat javelin-wounds.”

The book ends with “How to Practice True Economy,” a chapter-long rumination on the treats she thinks we all miss most from peacetime: shrimp paté, eggs with anchovies, Boeuf Moreno, a fricassee of chicken with brandy and a pint of cream, a crème-brûlée-adjacent pudding called “Colonial Dessert,” and, my favorite, “Fruits aux Sept Liqueurs,” a wildly indulgent fruit salad that requires marination in six different liqueurs, with a bath of half a bottle of demi-sec Champagne at the last moment.

On this variety of spectacle and indulgence, my heart is split. On the one hand, this is perhaps neither the wisest nor most salient moment to invest in a robust bar of obscure spirits with the intention of getting yourselves and your fruits incredibly drunk. And I must admit my early spring interpretation won’t include the peaches, plums, and wild strawberries (“wood strawberries,” she calls them, bringing to mind a Hansel-and-Gretel-like image of a search for them on the edges of forests). On the other hand, deeply fraught and disturbing moments of societal dysfunction always stoke my desire to remind myself and others that if you can swing it, there truly is no point in delaying joy. You never know what tomorrow will bring, and for the few small moments of delight and silliness this will snatch back from the Wolf, I’m willing to risk the next day’s headache.

FRUITS AUX SEPT LIQUEURS

From How to Cook a Wolf, by M.F.K. Fisher

Put into an ample bowl the following: slices of orange, tangerines, and bananas; pitted cherries; wood strawberries and peeled grapes; sliced peeled peaches and plums and ripe pears. Sprinkle them with sugar and a little lime juice.

Pour over them a liquid that has been made of a wineglassful each of the following but no other liqueurs, all mixed thoroughly together: brandy, kirsch, Cointreau, benedictine, maraschino, and a touch of kümmel.

Stir the salad lightly and put on ice for two hours. Just before serving, pour half a bottle of demi-sec Champagne over it.