For John Birdsall, the confluence of cooking and queerness goes way back. Birdsall started his cooking career at Greens, the restaurant that originally opened as part of the San Francisco Zen Center in the 1980s. He also wrote about food for “California’s gay and lesbian newsweekly,” the now-gone San Francisco Sentinel, among many other publications.

But it was “Your Food Is So Gay,” his 2014 essay in the quarterly food magazine Lucky Peach, that got the attention of people across the country. Turning its back on glossy food porn and chef portraits, the magazine was edgy and compulsive, filled with streetwise bluster and irreverent deep dives into iconic dishes along with intermittent offensiveness — Anthony Bourdain was a contributor, after all.

In Lucky Peach, Birdsall wrote about kitchen injustices he’d endured: “Even in San Francisco, gayest city in America, homophobic dicks got all the prime line positions in the places I worked.” But he also wrote about childhood memories of the rich roquefort-encrusted burgers his family’s neighbors, Lou and Pat, made, “calibrated for adult pleasure,” which he looks back on as offering an inkling that gay sensibilities could release American cooking from the bland strictures of home economics.

Birdsall knew at the time that he was coloring outside the lines by surveying the intersection of food culture and sexual identity. “I admit, it’s tricky pinning something as sprawling and amorphous as modern American cooking to anything as poorly defined as a queer point of view, and an exclusively male one at that,” he wrote.

But before him, few had excavated food’s sociological dimensions with his kind of unapologetic, iconoclastic gusto. He won a James Beard Award for it. The Man Who Ate Too Much, Birdsall’s excellent 2020 biography of Beard, followed. In it, Birdsall did not shy away from the difficulty and sadness of Beard’s intensely influential yet closeted persona.

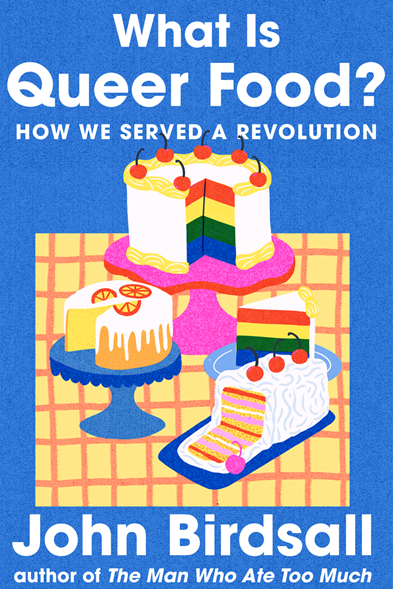

Now, in What Is Queer Food? How We Served a Revolution (Norton, 2025) Birdsall returns to his 2014 thesis, casting a much wider net. At a time when the government is racing to eliminate queer voices from the American story, his account feels like an act of resistance.

Birdsall is writing about a world for which he has deep sympathy and affection. But his writing is neither sentimental nor politically neutral. If the Lucky Peach article “let something slip out of the bottle,” as Birdsall told Claire Lower in an interview published in Milk Street last month, his most recent work upends the flask and pours with abandon.

His prose is engaging — old-fashioned storytelling mixed with an occasional dash of academic jargon and a fair amount of personal musing. Some readers may wish for more of the depth found in his Beard biography, but the voice here is passionate and the characters fascinating.

Birdsall invites us to queer restaurants, bars, and dinner party salons to meet the queer people, often closeted, who have been significant to the development of food culture in this country. He examines the ways they resisted and even flourished on the margins of social prejudice, economic sanctions, and legal prohibitions.

We are reacquainted with Alice B. Toklas and Gertrude Stein and with Stein’s peculiar cookbook, which Birdsall finds larded with coded lesbian references and with recipes that turn the conservative nature of cookbooks upside down with, for one thing, an emphasis on the killing that precedes cooking: “Before any story of cooking begins, crime is inevitable.”

Then there’s Craig Claiborne, who was born in 1920 in the Mississippi Delta, where his high school math teacher called him a sissy and where he was regularly assaulted by students who perceived his homosexuality. It’s a long way from Sunflower, Miss. to the New York Times, where he transformed the food section into an important cultural touchstone for New York and the nation. But, according to Birdsall, Claiborne’s early trauma was never far away. He was “always the boy getting his face pounded on Indianola pavement. The fear that formed in Mississippi never healed, never faded.”

We also encounter lesser-known names like Harry Baker, the gay man who invented the chiffon cake. Once again, in Birdsall’s view, it’s not only Baker’s sexual desires that make his cake queer: in his merging of yellow-rich batter and fluffy white sponge, he “ignores the tradition of the inescapable binary” and “shows the expansion of pleasure that is possible in the defiance of limits.” This kind of creative interpolation is emblematic of Birdsall’s style as he weaves his queer readings into the historical record.

As significant as his chiffon cake was, Baker didn’t last long once General Mills bought the rights to his recipe. He was promptly replaced by Betty Crocker, that fever dream of American middle-class heterosexual domesticity. The queer origins of this quintessential American dessert were erased, Birdsall writes, “sanitized in a process of home-ec reinvention.”

Yet another character is Esther Eng. Born in San Francisco to Chinese immigrant parents, Eng was a cross-dressing, openly lesbian film producer and director who eventually became a New York City restaurateur with five establishments, including Eng’s Corner, “a bar that was known to gay people.” Of Eng, Birdsall writes, “She seemed determined to live as if bigotry toward Asians, toward women, toward lesbians, didn’t exist. … What Esther displayed was the attitude of a warrior.”

It’s Eng’s warrior mantle that Birdsall himself seems to be taking up in this work.

Not all of those profiled in the book are cooks or food writers. One chapter, Hungry in Paris, tells of Americans in self-imposed exile in Paris in the late 1940s and early ’50s. We read how queer Black writer James Baldwin and his friends and lovers gathered at the table of Mary Painter, an American Embassy economist, in her Left Bank apartment to eat, smoke, drink, and debate. These are people “refusing to live the lives they were expected to slip into at home,” Birdsall writes, their meals together exemplifying both “a queer ethic of nurturance” and “an act of defiance” in a hostile world.

Birdsall’s historical road trip to the culinary sanctuaries where queer people found refuge includes stops at restaurants like the Paper Doll in San Francisco and New York’s Café Nicholson, where Edna Lewis was chef. Restaurants and cafés like these were safe spaces where queer people could take off the straight drag they used to pass and be themselves for a little while. The author visits these “hubs of safety,” he writes, “to roll the taste of queer deliverance across my tongue.”

In choosing to write about Lewis, Birdsall is expanding the definition of queerness beyond romantic or sexual interest. (He writes that he has no insight to offer into her romantic leanings.) Rather, she’s part of the story because “in the months after World War II is declared done, in the frenzy of remaking, before regimes of social conservatism harden with the Cold War, there’s a queer push to break out of our straitjackets of invisibility.”

Lewis’s restaurant, Café Nicholson, “is perhaps the only public restaurant in 1949 where queer people can gather out of doors in New York City to look at each other. To just … be.”

According to Birdsall’s account, outsider places like Lewis’s generated food philosophies that countered conventional perspectives, celebrating the exotic, the sensual, and the imperfect — picture James Beard mixing soufflés with his hands.

Toward the end of the book, Birdsall poses questions about the future of queer food. We don’t get answers; how could we? But where Queer Food is most hopeful is in its delivery of dynamic stories of the ways marginalized queer people found voice and influence — not only in the food world but in the larger culture — even in the most oppressive eras.