Cookbooks aren’t always for cooking by. That’s what we heard when we asked a few dedicated local cooks about their favorites. These kitchen volumes are for bringing back taste memories and traditions and places held dear. Sometimes they are practical advisers. But they can also be pure escapism. None are the latest. Maybe the best cookbooks to give are ones that have been well loved for a while — and have the spattered pages to prove it. —The editors

Irma S. Rombauer and Miriam Rombauer Becker: Joy of Cooking

If you’ve got a copy of Joy on your shelf, you’re ready for almost anything in the kitchen. Joy of Cooking works when the power is off and the internet is down. And it works when neighbors leave a goose on your porch on Christmas morning.

Whether this was a test of us newcomers from the city or a true country welcome doesn’t much matter. It was Joy of Cooking that took us from plucking to checking for birdshot before braising that bird.

A treasured gift from my mother-in-law, my expansive fifth edition circa 1967 is a collaboration between Rombauer and her daughter. Such vintage editions are available in used bookstores and online. Critics find updates after the fine sixth edition lacking.

With its conversational style, my version is delightful to browse as pure escape into nostalgia. But for me it pointed a way forward. Empowered with rudiments like basic béchamel, I advanced to Julia’s tutelage in the art of French cooking.

Here, one can find instructions on building a firepit: line it with rocks, but never shale, which when heated might explode. Reading last night, I learned how to set a formal table, right down to the correct placement of cigarettes and ash trays.

Around the holidays I often consult my cherished Joy, which packing tape holds together. It works when I need accurate information fast: Is the turkey done? What’s the ratio of buttermilk to cream for crème fraîche? What about those ginger cookies that stay firm when you hang them on the tree as ornaments?

If all but one of the hundreds of cookbooks and food histories on my shelves had to go, this is the one I would keep.

P.S.: Goose is best braised and enjoyed young. As the neighbor advised us when we expressed thanks for his gift: “Best thing you can do with a tough old bird like we get around here is put it in the crockpot with a can of mushroom soup and cook it all day.” —Carol Rizzoli

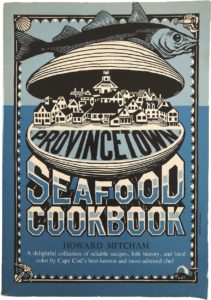

Howard Mitcham: The Provincetown Seafood Cookbook

The Provincetown Seafood Cookbook is something I go back to read often. It’s grounding. It’s not so much a cookbook as it is a piece of cultural anthropology. A sincere love letter to a very special place that maybe doesn’t totally exist anymore.

I bought my copy in 1991 when I first moved to the Outer Cape from New Jersey. The stories it told helped me connect to this spit of sand on a mystical, pagan level. It teaches respect for a place, the people, a simpler lifestyle, ceremony, for the ocean and for the fish.

The recipe for Squid Stew (page 151) is as simple and true as it is transcendental. This book is the closest thing to a bible in my house. First published in Provincetown in 1975, it was long out of print, but it’s once again available (Seven Stories Press, 2018). Do yourself — or any cook who cares about this place — a solid and grab a copy. —Tony Pasquale

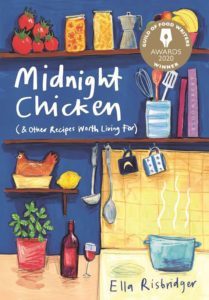

Ella Risbridger: Midnight Chicken & Other Recipes Worth Living For

When I got this cookbook, I read it like a novel, cover to cover. It turns out, that was exactly the right choice. It begins with three things to remember: “1. Salt your pasta water. 2. If in doubt, butter. 3. Keep going.”

Part narrative about the lifesaving power of nourishment, companionship, and care, and part comfort food extravaganza, Midnight Chicken (Bloomsbury, 2019) seems to me best at this time of year. In my house, it has become the cookbook we turn to as soon as the sun dips below the horizon before 5 p.m.

Risbridger is English, so the recipes skew toward British treats (hello, Slightly Charred Cauliflower Cheese), but also include tributes to the Indian, Vietnamese, and European immigrants who have shaped food culture there. She’s inspired me to do some things I never would have done on my own — getting up early to bloom yeast for pikelets, baking muffins on a whim, roasting fresh tomatoes for tomato soup — and also improved my ability to do things I already loved, her challah recipe being the most notable example.

Intertwined with each recipe you’ll find grief and its antidotes, tender inside jokes the author exchanges with people she loves, cheeky illustrations by Elisa Cunningham, and absurdly cheering ideas like how you should pack a hot baked potato in your pocket for a winter hike with a built-in snack.

Risbridger also describes some of her most remarkable kitchen disasters (a pork pie experience that truly would have tempted me to burn the house down), which humanize the somewhat unbelievable sweetness present elsewhere. This book is about using up the bits in the cupboard and crisper drawer, never using three dishes when you can use one instead, and, occasionally, when you feel up for it, spending hours making something very special. The recipes in this book made me love it, but the writing gave it a permanent place on the bookshelf. —Rebecca Orchant

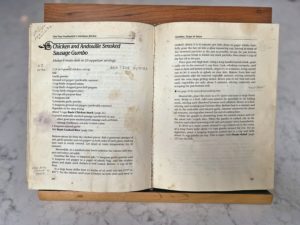

Paul Prudhomme: Louisiana Kitchen

Shortly after I graduated from college I moved to Philadelphia. The culture shock was profound. I hadn’t really wanted to leave New Orleans but pulled up stakes for love. Philly seemed gritty and bleak. Nothing was familiar — not the architecture, not the accents, not the weather, and certainly not the food.

Biting into my first Philly cheesesteak, I pined for a shrimp po-boy from back home. But I didn’t really know how to cook back then. Offering advice over the phone, my mother and grandmother weren’t much help — they didn’t really use recipes, instead cooking things “until you can see it’s ready” and measuring ingredients in idiosyncratic sprinkles, dabs, and handfuls.

One day I saw a copy of Paul Prudhomme’s Louisiana Kitchen (William Morrow, 1984) in a used bookstall at the Reading Terminal Market. On the jacket was a big man with a big smile surrounded by a whole lot of sausage. Somehow that image communicated to me that Prudhomme was someone I could turn to in this moment of dislocation. I bought the cookbook, which I think was my very first.

In his introduction, I learned that Prudhomme was from Opelousas, the Louisiana town from which my family hailed. I took comfort in that and read the entire book, cover to cover, marking the familiar dishes I wanted to make.

Mercifully, Prudhomme used conventional measurements rather than dabs and handfuls. More important, he revealed complex and nuanced versions of the everyday food I knew so well. During those early weeks of my exile, Louisiana Kitchen became a sort of companion. All these years later, the book is still my go-to, though the jacket is long gone, and it’s full of scribbled notes and splatters. Louisiana Kitchen is widely available used, with the same smile-and-sausage cover photo that first caught my attention. —Edouard Fontenot

Mary and Vincent Price: A Treasury of Great Recipes

When I was 10 years old, I started spending afternoons with Vincent Price. Not watching horror films. Reading the legendary actor’s cookbook.

Price was a passionate cook, art collector, and traveler, and A Treasury of Great Recipes is a serious cookbook. Originally published in 1965, it is a collection of recipes and menus gathered by Price and his second wife, Mary, from their favorite restaurants and adapted to their Hollywood kitchen.

The padded copper tome seemed to me to be something like a sorcerer’s book of charms. In it, I learned about chervil, sorrel, and savory. I pored over recipes from venerable restaurants like the Four Seasons, Sardi’s, and Antoine’s. I read about the cuisines of Italy and Mexico and the Indonesian influence on Dutch cooking. The book was a portal to the cooking and travel that I knew would someday become part of my own life.

Here you’ll find recipes for Chicken Stuffed With Black Truffles from the late great La Pyramide in Vienne, France and for sopapillas from the Santa Fe Super Chief, the train that connected Chicago and Los Angeles. It is unapologetic about offal, cream, and butter. It includes an homage to New England cooking. And it sings the virtues of a ballpark hot dog.

I still like spending the occasional afternoon with Vincent, agreeing with his insistence that great food is defined not by its expense or luxurious surroundings but by the quality of local ingredients, the care of the cook, and the joy of hospitality. I’m tempted by recipes for mussels in cream, croque monsieur, and peas with lettuce. There are some cringe-worthy head notes that are more Mad Men than modern. But gems, too, like “the coffin bench where popovers rest in peace.” And how can you not want to try the Potted Shrimp recipe from his besties, the Boris Karloffs?

Original copies are pricey collectors’ items, but the reprint (Dover, 2015), which has won praise from Thomas Keller, is within reach. If you find it at a yard sale or in one of the Cape’s used bookstores it will make the perfect gift for anyone who reads cookbooks like novels. —Katherine Alford

Howard Mitcham: Clams, Mussels, Oysters, Scallops, and Snails

I don’t have a favorite cookbook. I rarely follow a recipe as printed in a book. I see recipes more as guides to creating something with the ingredients I have on hand. That’s not to say I don’t appreciate how much work goes into producing something worthwhile. I have been working on my own cookbook for years — and you see where that’s gotten me.

One must-have cookbook is Salt, Fat, Acid, Heat by Samin Nosrat (Simon & Schuster, 2017). This one helps you understand the basics but also dives into the science of cooking and recipe building in an approachable way. But Chad Robertson’s country day loaf recipe in Tartine Bread (Chronicle Books, 2013) is so rewarding. You must first master the natural yeast before you can attempt to make a loaf of bread. This can take weeks. If you are making pasta or a Bolognese, you need Stir (Harper Collins, 2009) by my friend Barbara Lynch.

Howard Mitcham’s Provincetown Seafood Cookbook is a classic, but I especially like his memoir, Clams, Mussels, Oysters, Scallops, and Snails (Parnassus, 1990), which has many great stories of places and people of Provincetown like Clara Cook, who owned Cookies Tap Restaurant, or John Gaspie, who was the town’s shellfish warden many years ago. Mitcham’s books aren’t just full of recipes, they are full of culinary history, which gives us a greater understanding of the why of the how we prepare our food. The Why of the How: maybe that is the title I’m looking for. —Mac Hay