ORLEANS — In April 2016, about 25 therapists, social workers, and friends gathered in a circle at Nauset Regional High School to discuss the future of the Cape Cod Institute.

The continuing education center in Orleans had offered courses for mental health professionals since 1980. As founder Gil Levin neared retirement, he wanted to make sure the place survived him.

“He often said to me, ‘It’s like planning your own demise,’ ” says Molly Eldridge, his longtime deputy. “It was difficult, but it was important to him.”

In the late 1970s and early ’80s, three major psychology learning centers opened on the Outer Cape: the Gestalt International Study Center in 1979, the Cape Cod Institute in 1980, and the New England Educational Institute (NEEI) in 1984. They cemented the Cape’s reputation as a haven for analysts from New York and Boston, whose seasonal migration the New York Times once called the “August abandonment ritual” to “Shrinkland.”

The original founders of all three centers have retired or died, and the pandemic made it difficult to sustain in-person programs on the Outer Cape. NEEI closed in 2022 after a short-lived affiliation with Boston University’s Chobanian & Avedisian School of Medicine, and the Gestalt Center sold its headquarters in Wellfleet that same year.

The Cape Cod Institute celebrated its 45th anniversary this year. It has endured under new director Kathryn Rorke by offering shorter courses and hybrid learning options. But even with a committed following of students, faculty, and local partners, it faces the same uncertainty that has plagued its peer institutions.

“We haven’t reached pre-Covid numbers at all, and our online numbers will never be high because we’re offering experiential learning,” says Rorke. “I’m still trying to figure it out.”

Rules for Dialogue

The rules for that 2016 dialogue circle were simple: make no eye contact and speak only when spoken to.

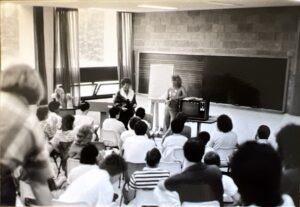

Robert Hartl, a management professor at the College of St. Scholastica, asked “provocative questions” about the Institute and told people to address their replies to a backpack at the center of the high school music room, a setting chosen, he says, for its size and “fairly good acoustics.”

According to Hartl, many participants said Levin should find someone to manage the Institute “on the ground” while the aging psychologist remained an “inspiration and guiding light.”

Others wondered whether the Institute should have purchased its own building years earlier, a decision, they said, that might have allowed it more control. But Eldridge says their friends from the Gestalt Center pushed back.

“They were moaning about the burdens of owning brick-and-mortar buildings,” she says. “They said it was one of their biggest mistakes.”

The financial model for in-person continuing education was already brittle. Between 2018 and 2026, the research firm Syngene projected the online learning industry to grow 9.1 percent per year. At the same time, the rising cost of housing on the Outer Cape was making it increasingly difficult for mental health professionals to afford a weeklong vacation here.

“It used to be that you could write off your week of continuing education, and your family could stay in a cottage in Eastham,” says Eldridge. “It’s not that way anymore.”

In the summer of 2020, therapists were quarantined in their homes, making online coursework more appealing. “As things went online,” says Ronald Siegel, a psychiatry professor at Harvard Medical School, “it became harder and harder to break even or turn a small profit” hosting in-person classes.

NEEI founder Robert Guerette says that he retired in 2019 simply because he was getting older. He had donated the conference to his alma mater, Boston University, in hopes that it could continue “forever and ever.”

But in October 2022 B.U. reported that the pandemic’s effects had “severely hampered” its ability to offer in-person courses in a “cost-effective manner … and as a result, we are ending the series.”

“They could have gone online and made a fortune,” says Guerette.

In June 2024, the Gestalt Center sold its 4,400-square-foot headquarters to the town of Wellfleet for $1.7 million. President and CEO Laurie Fitzpatrick said at the time that relocating to Boston was a “strategic move to be a little more centrally located.”

“Some of us hoped that we could find a way to promote the center to be an attractive in-person location, but that turned out not to be,” says psychotherapist Stuart Simon, a senior faculty member at the Center. “Why would someone travel here from South Africa when they could just turn on their computer?”

Insolvency Ensues

Levin died in March 2020, leaving the Cape Cod Institute in a state of financial emergency.

Some students had already paid more than $600 for the Institute’s summer session, but according to an email sent to registrants from Levin’s son, Alex, they would not receive cash refunds. “The company simply does not have the money; it has been spent on nonrecoverable operating costs,” he wrote, adding that students could transfer their registration to another year if the Institute returned.

“When I wrote that, the Institute was about to become insolvent; then it did become insolvent,” Levin says. “It quickly became clear that there would be no more Cape Cod Institute.”

The program shut down.

Rorke, who had briefly co-directed the Institute in 2018, says she began receiving calls from faculty and students asking if anything could be done. “I gained access to the CCI logo and the name and started building it back slowly,” she says. “I knew that if I didn’t do something in 2021, the program wouldn’t make it.”

The Institute posted a video on March 29, 2021 of waves crashing beneath a purple sky with the caption, “Enjoying the glimmers of Spring and looking forward to Summer!” It announced that there would be a shortened session from Aug. 9 to 27 that year.

Rorke offered places to those who had paid for the 2020 summer session, says Levin. He felt an “incredible psychic relief” that she had helped the Institute “come back to life.”

Some faculty waived their speaking fees for the shortened session. They were willing to teach for free because “they wanted this place to survive,” Rorke says. “It meant something to them.”

Einstein on the Wall

This year, the cafeteria at Nauset Regional Middle School doubled as the Cape Cod Institute’s bookstore and lunchroom. The space was clean, filled with light, and nearly empty on a weekday morning in July while students and teachers worked in nearby classrooms.

According to Rorke, cafeteria employees can often guess the week’s courses based on “what happens at the buffet table.” During “ADHD week,” she says, laughing, “they find stuff everywhere.”

On one wall, staff had pinned all of the Institute’s brochures in a sprawling collage. In the 1980s and ’90s, when the program was sponsored by the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in New York, nearly every cover featured a Linda Louis cartoon of Einstein with sunglasses on his head.

Starting in 2000, his face gave way to paintings of waves, dunes, and churches by local artists. The offerings shifted as well: three-, four-, and five-day hybrid courses on organizational practice, EMDR, and psychotherapy shared space in the catalogue.

When students left their classrooms at midday, they approached the buffet, blue lanyards swinging from their necks as they moved between the fruit salad and the brownies.

Srikanth Seshadri, who coaches CEOs through “demanding, tough jobs,” said he values the Institute’s “top-notch thinkers” on organizational development. Daniel Rezende, whose Connecticut nonprofit offers therapy to children and young families, said that he sends several employees here each summer to boost “overall culture and morale.”

For longtime attendee Phil Muisener, a clinical social worker in Connecticut, the Institute’s revival — from “limbo status” in 2020 to a bustling cafeteria in Orleans five years later — has been remarkable. He credits its new leaders.

“Kat Rorke and manager Lori Lerma bring heart to the place; I can’t emphasize that enough,” he said. “It rose from the ashes.”