EASTHAM — Change is on the horizon for properties that still rely on a cesspool, an outdated system for treating human waste that typically consists of an underground pit or storage tank. Eastham Health and Environment Director Hillary Greenberg-Lemos told the Independent last week that her department wants to see all the town’s cesspools upgraded to more environmentally friendly options such as Title 5 septic systems.

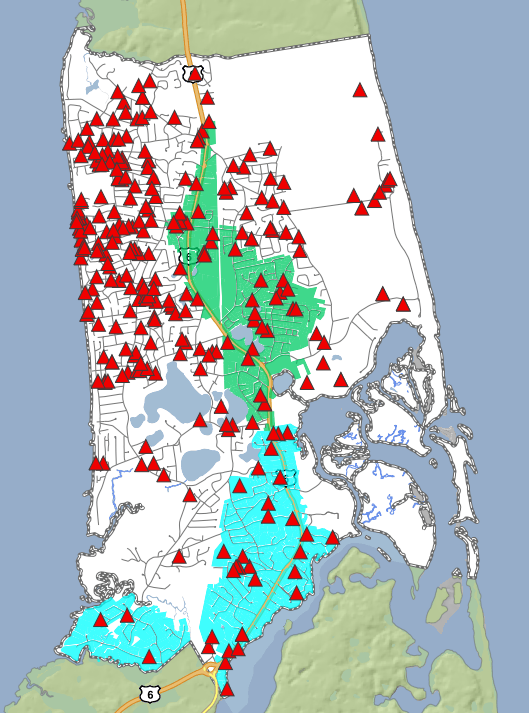

A March 2024 survey of property records identified 278 cesspools in Eastham, representing about 4 percent of its developed lots, Greenberg-Lemos said. They are scattered throughout town but are most numerous north of Great Pond and west of Route 6.

Installing a cesspool has been illegal in Massachusetts since 1978, but the town doesn’t have a regulation that requires all property owners to replace existing cesspools with septic systems. Town staff and the board of health have been discussing ways to implement such a regulation since last year, Greenberg-Lemos said.

Those discussions moved to the back burner this spring when the town was seeking approval for a municipal sewer system for the Salt Pond watershed. Now that the $170-million project has been approved by town meeting voters — and with the end of the summer tourist season fast approaching — health board discussions are set to resume.

“We’re just in the infancy stage of determining where we want to go,” said Greenberg-Lemos. The board has reviewed cesspool regulations in neighboring towns and held a public workshop last December to gather input from homeowners, she said.

“The most comments we got were from second-home owners or people who use their home so infrequently that they didn’t understand why they needed to upgrade them,” Greenberg-Lemos said. “It’s going to be a consideration of the board, because we heard a lot of that.”

Nonetheless, whatever rules are finally passed will likely apply regardless of property usage, she said. “We never know from a health department regulatory standpoint how you’re using your property,” she said. “What if something happens and you move here full-time next month?”

Only 32 of the cesspools are located within the town’s planned phase 1 sewer zone, which will serve 786 parcels around Salt Pond, Ministers Pond, and Route 6 as far north as Nauset Road. About 30 are in the planned phase 2 sewer zone, which covers Route 6 from Town Hall to the Orleans rotary, as well as the area south of Boat Meadow Creek.

That means the town’s two planned sewer districts will address only about 22 percent of the town’s cesspool problem.

Pollution Effects

According to Erika Woods, the deputy director of health and environment for Barnstable County, cesspools are usually built with porous walls that allow liquids to seep into the surrounding soil while solid waste settles to the bottom. The hope, Woods said, is that bacteria already present in the soil will break down harmful substances as they emerge through the cesspool’s walls.

But that isn’t always how it works. “Many of these cesspools were installed so many years ago that the soils might be overloaded, so some of the discharge is going directly into the groundwater,” Woods says. That results in nitrogen pollution that causes algal blooms in wetlands and ponds and threatens the drinking water supply.

Water pollution becomes most obvious to residents when it causes pond and beach closures — which former Eastham Conservation Agent Henry Lind said are increasingly common, thanks to rising water temperatures due to climate change.

Bacteria stay alive longer in warm seawater than cold seawater, which is why closures are more common during the summer, Lind said. Peat banks and salt marshes are “like a petri dish” for bacteria, he added.

This summer, both South Sunken Meadow Beach and Cooks Brook Beach were closed because of an exceedance of enterococci, a bacterium that indicates the presence of fecal matter in water.

Unlike nitrogen pollution, fecal matter is almost certainly not from cesspools, Lind said. Those beach closures were more likely due to animal feces being washed into the water by rainstorms.

Nonetheless, “we have a situation where the raw sewage is not treated before it goes down into the groundwater,” Woods said. In addition to nitrogen, bacteria and viruses can reach groundwater by that route, she said.

Even Title 5 systems aren’t always enough to reduce nitrogen pollution, Lind said. That is why the town needs a sewer system around the Salt Pond watershed — because “the latest iteration of the DEP’s guidance is that even Title 5s aren’t working in some places.”

Eastham has also set rules for when Title 5 systems need to be replaced with even more advanced Innovative/Alternative systems — usually when a property borders a wetland or there is groundwater only four feet below a septic system’s leaching field.

The Current Rules

Right now, cesspools in Eastham need to be upgraded to Title 5 systems only if they experience “failure” — needing to be pumped four times in one year, for instance, or leaking overflow onto the ground. Cesspools are also considered “failed” whenever a property is sold or transferred to someone other than a surviving spouse or if the owner seeks a building permit for the property.

The rules are stricter in some other towns. In spring 2021, Truro became the first Outer Cape town to require the removal of all cesspools within two years.

One reason that cesspools are allowed to continue is that they can be expensive to replace.

A Title 5 system typically costs between $12,000 and $17,000, depending on soil conditions, lot size, and contractor availability, according to Eastham’s health dept. Last year, Truro’s health dept. estimated the cost for a system for a three-bedroom house at $20,000.

Financing to cover those costs is available through the Cape Cod AquiFund, which offers loans at 4 percent interest over a 20-year term. The long timeline and low interest rate do make a difference — under those terms, a $20,000 loan would cost about $120 per month to repay.