TRURO — Two rounds of testing last winter and spring resulted in the discovery of PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, in the well water of five private homes in Truro: four downhill from the town’s DPW facility and one downhill from the transfer station.

Although the tests that discovered the toxic chemicals in the well water at private homes were conducted in January and April, the town’s search for PFAS contamination began several years ago, according to DPW Director Jarrod Cabral, the town’s environmental consultant, Bryan Massa, and Health and Conservation Agent Emily Beebe. Truro decided to test for PFAS in monitoring wells around its retired landfill in 2023, even though state law did not require those tests.

“My understanding from the state Dept. of Environmental Protection is that Truro was one of the first towns in the state to test its landfill,” said Massa. “When we reported the results to the DEP, they were pretty surprised that the town had pre-emptively tested for PFAS. They said they were working on making it a requirement, but we were ahead of the curve.”

“We decided it’s better to find out and manage it now than be forced to comply later on,” said Beebe. “It’s about protecting people’s health.”

Cabral said he requested extra funding for the tests from the town’s budgetary task force, which is composed of two select board members, two finance committee members, the town accountant, and the town manager, in the fall of 2022. A series of monitoring wells around the transfer station were tested in May 2023, and three came back positive for PFAS contamination, although at relatively low concentrations that town officials took as good news.

“It was not nearly as bad as we thought it would be,” Cabral said.

The state requested follow-up tests at three homes downhill from the capped landfill, and those tests showed no contamination in their well water.

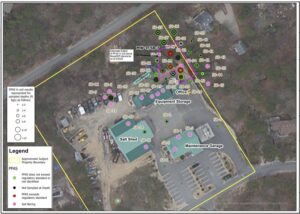

In July 2024, however, the town was also making plans to rebuild its DPW facility about a mile away, starting with an environmental assessment of the roughly two-acre site. Ground-penetrating radar showed buried metal behind the road salt shed, which turned out to be old snowplow blades, six oil drums, and a 275-gallon oil tank, which was leaking.

Extensive soil tests were done after that discovery, Cabral said, and they turned up a PFAS contamination “hotspot” about 50 yards farther east, likely due to years of “catch basin sediments” that had been dumped there. Those sediments are composed of dirt and debris that are excavated from stormwater drains by DPW maintenance machines — a concentrated stew of highway runoff that turned out to contain loads of PFAS.

‘Forever Chemicals’

PFAS are sometimes called “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in the environment. They are harmful to the endocrine, immune, and reproductive systems and are linked to certain cancers, so when they were found in the five houses’ wells, the town, in accordance with state law, began to abate the risk to the people living there: first by providing bottled water for drinking and cooking, and then by installing point-of-entry treatment systems, or POET systems, at the homes to remove all detectable PFAS from their water.

Two of those systems are now operational, two are installed and undergoing start-up tests, and the fifth required some excavation in the house’s crawl space and will be installed soon, according to Cabral and Massa.

Each POET system costs just over $8,000 to buy and install, Cabral said, and the first year of operation and maintenance costs another $8,000 per household, according to Massa. In subsequent years the town will pay about $3,000 to $5,000 to maintain each system, and they will continue to run until a $3.2-million remediation effort at the DPW site can stop PFAS from leaching into groundwater there.

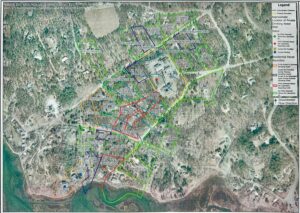

The 2024 soil tests at the DPW property had triggered state laws that led the town to send letters in December asking 23 neighboring property owners for permission to test their well water. Nine owners either did not respond or did not grant permission, and the other 14 were tested in January 2025.

Results received in February showed that 11 homes had no PFAS in their well water and three had detectable PFAS: 28 Town Hall Road, 30 Town Hall Road, and 25 Castle Road.

In late 2024, the state DEP had also asked the town to take a second look at the transfer station site, said Beebe, and test a second batch of seven more houses downhill from the three that had already been tested. Only five of those homeowners gave the town permission to take samples in January, and the well water at one of those five — 48 South Pamet Road — tested positive for PFAS in February, although at a very low level, according to Massa: 2.09 parts per trillion.

At that point, the town began delivering bottled water to the four houses and making plans to install POET systems in each.

The town sought permission for a second round of tests at sites near the DPW in March, Beebe said, including seven property owners who had not responded to the first call for testing and 11 new properties farther downhill from the houses with positive tests.

Thirteen of those 18 homeowners gave permission to sample, and one more well containing PFAS was found at 3 Bridge Lane.

A third batch of 10 homeowners near the DPW were sent letters requesting permission to test in July, said Beebe and Cabral, along with six more homeowners near the transfer station. Some homeowners have now received three separate requests from the town.

“Our concern is for the folks who haven’t given us permission to test yet,” said Beebe. “This can be mitigated. It’s not the end of the world if you have PFAS in your well. We’re going to give you bottled water and then install a POET system,” and the town will conduct years of monitoring and maintenance at no cost to the homeowner, she said.

“We’re trying to do the right thing,” said Beebe. “This is about your health.”

An Emerging Contaminant

The POET systems are composed of three large barrels or tanks, each of which includes “granulated activated carbon and an ion exchange resin,” Massa said. The operating and maintenance costs are comparatively high because one of the three tanks is replaced every year.

The permeable underground barrier that the town will soon install around the DPW site will eventually allow the POET systems at nearby homes to be deactivated, Massa said.

“There will still be monitoring wells nearby, but the hope is that the groundwater will clean up and we’ll just verify every six months or year that there’s still nothing in it,” Massa said.

The town is responsible for paying for these systems under state law because town property was the source of the contamination, Massa said. If a private homeowner were to test her well water and find a significant amount of PFAS without there being an obvious source of contamination on the property, it could trigger the state to look at properties uphill in an effort to find the source.

“If there’s contamination that’s found, and it’s your contamination, then you become the responsible party and you’re on the hook for providing clean drinking water,” Massa said. “If you’re surrounded by a bunch of residences and there’s no known source, then it’s probably just background contamination from septic systems,” which does not trigger a requirement for abatement measures, he said.

“But if there’s an industrial manufacturer or carwash or something like that uphill, then the state may compel them to test, and it could become their responsibility to put these systems in,” Massa added.

“This is an emerging contaminant, and we’re going to be talking about it more and more,” Beebe said. The town’s public water supplies have already been tested, but PFAS “will be found in wells that have nothing to do with the town of Truro,” she said.

“PFAS are ubiquitous — they’re something we’re going to continue to find,” said Beebe. “It’s good that we’re testing for them.”