This article was updated on Aug. 2, 2025.

TRURO — In February, the town began delivering bottled water to four houses where well water tested positive for a group of harmful manmade chemicals called PFAS, or per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances.

A fifth property was found to have PFAS in its well water in subsequent testing in April and was also provided with bottled water by the town.

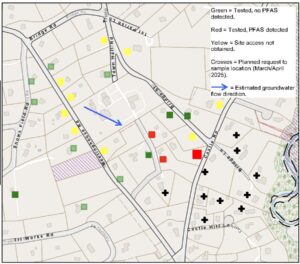

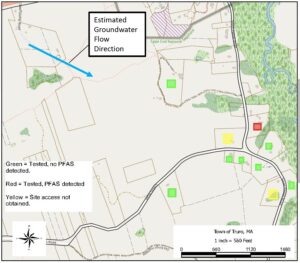

The four properties identified in February are 28 Town Hall Road, 30 Town Hall Road, and 25 Castle Road, which are near the town’s Dept. of Public Works facility, and 48 South Pamet Road, in the general area of the transfer station.

The fifth property identified in April, 3 Bridge Lane, is downhill from the DPW building.

Eleven other homes near the DPW have wells that tested negative for PFAS, according to a town report from February, and seven homes near the transfer station also tested negative.

The town has already installed water purification systems called point-of-entry treatment systems at four of the homes where PFAS were detected, and it will soon install a system at the fifth, according to Truro Health and Conservation Agent Emily Beebe.

Some of the purification systems have already been tested and cleared for operation, and the town no longer delivers bottled water to those addresses, Beebe told the Independent.

The other houses should have drinkable water again within “the next few weeks,” once the new systems have been tested and cleared, Beebe said.

In the meantime, water that contains PFAS can be used for bathing, but the town-delivered bottled water must be used for drinking and cooking.

Ellen Anthony, who owns the house at 48 South Pamet Road, told the Independent she’s been pleased with the town’s response to the problem.

Town officials and contractors have been exceptionally respectful and responsive, Anthony said, calling their efforts “super terrific.” The town has brought sufficient water, she said, and she appreciated that it came in paper containers rather than environmentally-unfriendly plastics.

PFAS are “an enormous and everywhere problem” that isn’t unique to Truro, Anthony said. “We’re totally a polluted mess on Earth.”

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warns that exposure to PFAS, sometimes referred to as “forever chemicals” because they do not break down in natural environments, can harm the endocrine, immune, and reproductive systems and increase the risk of some cancers.

According to the Centers for Disease Control, “nearly all people in the U.S. have PFAS in their blood,” but production of the compounds has declined in the past 20 years.

Regulations on PFAS in drinking water vary by state; in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Maine, six specific PFAS compounds may not add up to more than 20 parts per trillion in drinking water.

Truro does not only have to offer bottled water to homes that exceed that threshold, though — according to a state law called the Mass. Contingency Plan, it’s required to give bottled water to houses where any PFAS are detected if a town-owned property is the source of the contamination, Beebe said.. The well water at Anthony’s home was below the 20 parts per trillion limit, Anthony said — nonetheless, Beebe said, “We don’t want there to be any ingestion of it, even if it’s a super low level.”

The amount of PFAS in water samples can also vary over time, Beebe said, and providing bottled water protects against the possibility that there’s more PFAS in the water than a particular test indicated.

Testing of homes near the two town facilities took place in January, Beebe said. PFAS had been found at the DPW in September and at the transfer station in May 2023.

Three private wells near the transfer station tested negative for PFAS in May 2024, according to town reports, but at the state DEP’s request, a second group of homes in that area were tested this January, Beebe said.

All tests were done with the permission of homeowners, Beebe said.

Anthony said one of her neighbors had asked why the town tested Anthony’s home and not theirs.

“DEP regulatory guidelines determine who is tested and who is not tested,” said Truro communications coordinator Katie Riconda, adding that the guidelines provide for testing at homes that are within 500 feet of a known contamination site and also at a lower elevation. PFAS travels underground along with groundwater, which flows downhill.

Tim Dickey, who lives near the DPW at 25 Castle Road, said the town informed him “right away” after his water tested positive for PFAS.

Still, he worries about the water he drank before the town conducted the tests. “We don’t know when the plumes started,” he said, using a term that refers to PFAS contamination.

PFAS are often used in firefighting foams, waterproof clothing, waterproof food packaging, and nonstick cookware, among other common products.

According to a Feb. 26 report that Beebe forwarded to the Independent, the source of the PFAS contamination at the DPW site is “currently unknown but may be related to the historic placement of catch basin sediments and/or street sweepings behind the DPW office building.”

The board of health was briefed on the contaminated water at private homes at their March 18 meeting, according to meeting minutes.

Truro plans to continue to “sample the neighborhood — making sure whoever needs to be sampled has been sampled and the true extent of any contamination has been determined,” Beebe told the board of health on July 15.

At town meeting on May 3, voters overwhelmingly approved a $3.2-million debt exclusion that will pay to install a permeable reactive barrier around most of the DPW site. That barrier, once installed, will prevent PFAS from traveling further downstream.

The town is also investigating the possibility of installing a public water supply well that would serve the DPW, town hall, and several nearby houses, according to Beebe. In the meantime, town employees who work at the public works building and the transfer station are also drinking bottled water, she said.

Kits that town residents can use to collect well water for PFAS testing are available at Truro Town Hall in the health and conservation dept. office. The tests are done by Barnstable County’s water quality lab and cost $265.

Editor’s note: Because of inaccurate information posted on the Mass. Dept. of Environmental Protection website, as well as reporting and fact-checking errors, the address of one of the Town Hall Road houses where PFAS were detected in the well water was misidentified in an earlier version of this article published in print on July 31. The correct address is 28 Town Hall Road, not 25 Town Hall Road.

That version of the article reported that four houses were found to have PFAS, based on incomplete information from Health Agent Emily Beebe. After the article was published, Truro town staff contacted the Independent to say that a fifth house also had PFAS detected in its well water. That house, at 3 Bridge Lane, was tested on April 30, 2025, Beebe now reports.

The online version of this article was updated on Aug. 2 to more accurately describe when PFAS were discovered at the transfer station, when the first homes in that area were tested for PFAS, and when the positive tests at five properties took place. It also includes a clarification from Emily Beebe that the town is required by state law to pay for bottled water and filtration systems only when the source of PFAS is a town-owned property.