EASTHAM — Ever since the select board voted in January to begin planning for a residential tax exemption (RTE) in the upcoming fiscal year, opposition to the policy from part-time residents who would not be able to take the exemption has been repeatedly expressed in public comments at select board meetings.

Much of that opposition has been based on the idea that only people who need tax relief should receive it, and that the RTE would unduly reward wealthy residents of Eastham and punish some non-wealthy nonresidents.

The RTE was written into state law in 1979 as a local option that towns can adopt, and it offers greater tax discounts to the resident owners of less valuable property and lesser discounts, or none at all, to the resident owners of more expensive property.

That differential impact is because after all the exemptions are tallied, all remaining assessed residential value in town is taxed at a new, somewhat higher rate — and the resident owners of more expensive properties lose to the higher rate much of what they gained from the exemption.

Five towns on Cape Cod already have residential tax exemptions: Provincetown, Truro, Wellfleet, Mashpee, and Barnstable. On the Islands, the towns of Nantucket, Tisbury, West Tisbury, and Oak Bluffs have adopted the policy, while on the mainland, cities and towns including Cambridge, Somerville, Chelsea, and Boston use it.

The 19 towns in the state that already have the policy fit a pattern described in the summer 2019 issue of City & Town, a newsletter published by the state Dept. of Revenue: “Communities that choose to adopt the exemption often have the following characteristics: large cities or towns with many nonowner-occupied properties like apartment buildings, or resort communities with many seasonal residents.”

The legislative record for the 1979 law, House Bill 5594, describes Massachusetts taxpayers being “forced to the wall” by property tax increases, many of them the result of state mandates concerning public schools and benefits for town employees.

When the law was first passed, towns could exempt from taxation any amount up to 10 percent of the value of the average residential parcel in that town. The maximum was raised to 35 percent of the average value in the Municipal Modernization Act of 2016, and the Affordable Homes Act of 2024 allowed towns that accept a new “seasonal communities designation” to raise their exemption amount to 50 percent of the average value in the town.

Property values have risen rapidly in Eastham in recent decades — according to town records, in 2015 the median sale price in Eastham was $393,000 and in 2000 it was $192,300.

Eastham’s 2015 median home price was about 33 percent above the national median, according to U.S. Federal Reserve figures — but by 2024, the median home in Eastham sold for $816,000, according to the Cape Cod and Islands Association of Realtors, almost double the national median of $418,975.

“One reason people have trouble understanding the RTE is because they often think of it solely as a fixed exemption amount granted to full-timers,” said Phineas Baxandall, policy director of the Massachusetts Budget & Policy Center. “The relative impact of the two separate effects — the fixed exemption and the property tax rate increase — are different depending on the value of your property.”

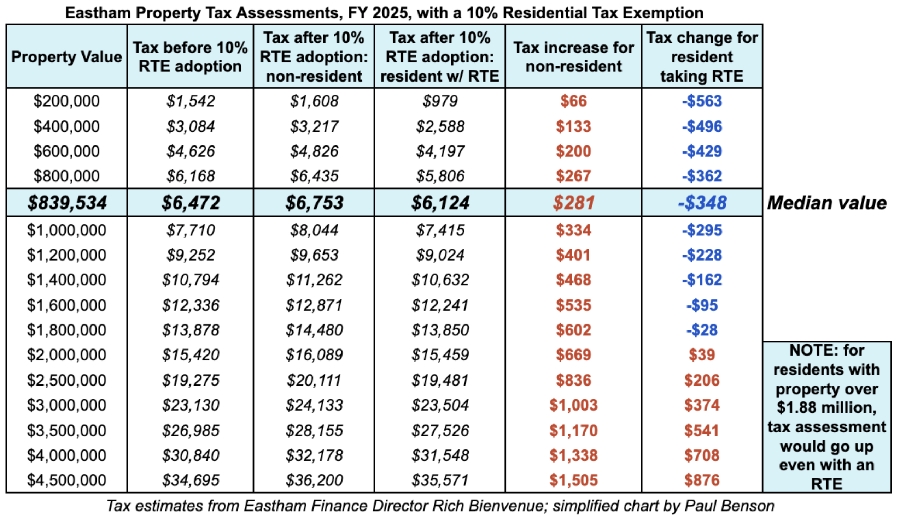

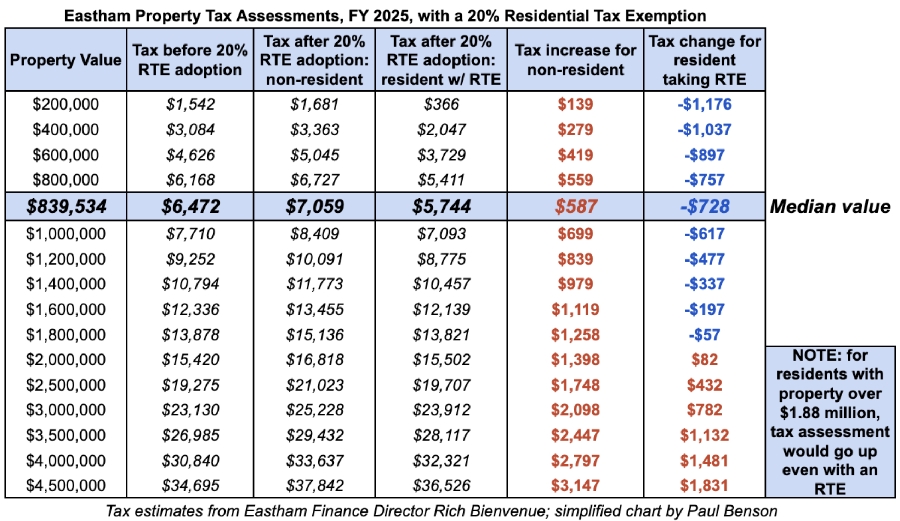

According to figures provided by Eastham Finance Director Rich Bienvenue, if a 20-percent RTE had been applied in the current fiscal year, it would have raised the tax rate on all remaining residential value from $7.71 per $1,000 of assessed value to $8.41 — about a 9 percent increase.

For a home worth $600,000, a 20-percent exemption followed by that new tax rate would have saved a resident homeowner $897 on their property taxes, according to Bienvenue’s data.

Because of the tax rate, the resident owner of a $1.6-million property would save only $197, while the resident owner of a $2-million property would actually pay more property tax than if the town did not adopt the exemption policy.

The impact on nonresident property owners also varies significantly. For the nonresident owner of a $600,000 house, a 20-percent RTE in the current fiscal year would have cost an additional $419, while the nonresident owner of a $2-million home would have paid $1,398 more, according to Bienvenue’s figures.

If the exemption had been set at 35 percent of the average residential value, the resident owner of a $600,000 home would have saved $1,683, while the nonresident owner of a $600,000 home would have paid $787 more.

Bienvenue has said that Eastham will likely begin with an exemption amount of 10 or 20 percent in the fiscal year that starts on July 1.

“I often hear opponents of the RTE criticize the exemption for its lack of means testing,” said Baxandall, who published an analysis of property taxes in the state in 2020, “but that characterization seems misguided. The RTE is highly targeted, insofar as the exemption makes it possible for local residents to afford their residence through a requirement on other people with multiple homes to pay more.”

Baxandall said the biggest problem with the RTE is its effect on rental housing. “It could potentially worsen housing affordability for renters if landlords pass on the tax increase in the form of higher rents,” Baxandall said, “so other efforts are necessary to help rental affordability.”

In Truro, the owners of year-round rental units can claim a residential tax exemption for those properties, while in Provincetown, owners can claim up to four RTEs per parcel if there are multiple units occupied by year-round renters. Those options, which were passed as home-rule petitions by town meeting voters in those towns and then approved by the legislature, won’t be available in Eastham for at least a year.

On March 17, Bienvenue told the select board that expanding the RTE to rental properties could be considered as “part of a package next year.”