An Undecided Voter

Liz Athineos, 71, owns the Bike Shack on Shank Painter Road in Provincetown and lives behind the shop with her mother and son.

“Most Greek Americans are Republicans,” Athineos says, “but I’ve always been a registered Democrat.”

That’s not unusual in Provincetown, where 92 percent of voters picked Joe Biden for president in 2020. But Athineos chose not to vote that year because she felt she couldn’t support either Donald Trump or Joe Biden. She is certain she’ll vote this year, but she still can’t decide for whom.

“I’m disappointed in both of my choices,” Athineos says, referring to Trump and Kamala Harris. “I was embarrassed watching them debate — I thought they were both tacky and childish and wouldn’t answer any of the questions.”

Athineos says she likes vice presidential candidates JD Vance and Tim Walz, finding their debate “polite and presidential.” She voted for Republican Mitt Romney in 2012 but also pines for Michelle Obama to run for president, saying that “she’s liked and respected and would win in an incredible landslide.”

“It feels like every day I hear some new bad thing” about Trump or Harris, she says. “I feel pushed around like a ping-pong ball, and I don’t see my values in either of them.”

Athineos travels often to Greece and worries that America is “hated like we never were” because of its actions overseas. She is upset that Israel is “blowing up hospitals in Gaza and neighborhoods in Beirut,” but she’s also upset by Biden’s attempts at canceling student loans, which she thinks is unfair to those who saved for college.

She has disliked Biden since his treatment of Anita Hill during Senate hearings in 1991, but she worries that her customers will take her distaste for Biden as support for Trump.

Trump and Harris are “both making fun of each other and feeding off divisiveness, and I feel like confusion is the result and the intent of all this,” she says.

Despite her frustrations, Athineos talks politics readily, including with the contractors who recently rebuilt her shop. “Everyone who works with their hands is voting for Trump,” she says, “even if they say they’re undecided. I’m disappointed with my party for talking down to working people, and I’m also worried that saying that could hurt my business.”

No matter who wins, Athineos says she is dreading the day after the election. “I think what happened after Jan. 6 last time is going to look like a picnic in the park after this one,” she says. “I just don’t have confidence in us anymore.” —Paul Benson

Considering a Straight Ticket

Truro resident Elena Rice, 45, says she likes to pick individual candidates to support rather than voting a straight party ticket. This year, however, plans for wind power installations in the Gulf of Maine means she could vote Republican up and down the ballot, she says.

“For the first time in my life, this issue may affect how I vote across the board,” Rice says. “We have so much to lose on Cape Cod if this gets supported.”

Rice and her husband, Bobby, have run Reel Deal Fishing Charters in Truro for 25 years. She is especially concerned about the effects of wind turbines on striped bass and bluefin tuna, the sport fish that sustain their business.

Rice says she hasn’t fully decided on her vote for president, but says she wants a candidate that won’t “fast track” offshore wind, which could mean Donald Trump.

Rice fears that Kamala Harris would follow the policy of the Biden administration and “dump billions of dollars” into clean energy and offshore wind.

She wishes there were “less extreme” options for president, she says — someone who understands climate change and would protect the environment while “being responsible with how taxpayer money is spent on renewable energy.”

“I don’t feel like either of those candidates fall into that category,” she says.

“Given the stigma that gets attached to people on the Outer Cape who say they’re going to vote for Trump, I’m hesitant to,” Rice says. “But sadly, this is the situation people are being forced into: potentially voting for a candidate that they may not agree with because of this issue.”

Rice says Chris Lauzon, the Republican challenging incumbent state Sen. Julian Cyr, is more open to her concerns about wind power.

“Every meeting or gathering I’ve gone to about offshore wind, Christopher Lauzon has been there and Julian Cyr has not,” Rice says. She has spoken with Cyr’s chief of staff about the shortcomings of BOEM’s plans and was dissatisfied to hear that Cyr still supports the wind energy leases.

Rice says she talks to many friends and neighbors about wind power, including some who support it. She sees those conversations as a learning opportunity, she says.

Some people say wind power is a key to solving the climate crisis but can’t explain why, and those conversations can get “uncomfortable,” she adds. “How is all the potential destruction in the Gulf of Maine going to solve climate change?” —Aden Choate

Voting With an Asterisk

Mike Sullivan, 30, a Provincetown artist and activist who has led pro-Palestinian demonstrations over the past year, says that voting alone falls short when America’s political system needs major transformation.

“The pathway to peace has always been through Arab and Jewish activists advocating for a ceasefire and a new way of thinking,” he says. “It is not through more violence or the death of a Hamas leader.”

Nonetheless, Sullivan is voting this year. “But I say that with the largest asterisk in the world,” he adds. He also says that people who choose not to cast a ballot on principle are still affecting the political system.

“Through our actions and through interpersonal ways of being, we’re voting every day,” he says. “We’re all involved in this, voters and nonvoters.”

His previous loyalty to the Democratic Party, which he says strained some personal relationships, has left him disillusioned. “It did things that I am so saddened by and that are so against my values,” he says.

When he and other pro-Palestinian activists demonstrated outside Kamala Harris’s fundraiser in Provincetown on July 20, Sullivan says, it was the first time they had experienced backlash from the public here.

“People swore at us,” he says. “They made gestures to us. They told us we were wrong. They called us Trump supporters. They told us to get out of town. They told us that we were crazy.”

That day left him exhausted — but Sullivan says that Harris is still more likely to engage productively on Palestine than Trump would. He doesn’t want to say how he’ll vote, but says he still has hope for change.

“What I have learned from being in a queer community is that we don’t have to settle and the world doesn’t have to be this way,” he says. “We can live in a world where we don’t have to support the military over health care, housing, and sustainability in our own back yard.” —Aden Choate

Not Skipping This Election

Eastham resident Justin Kennington, 45, doesn’t see himself as particularly political. “I’m not registered as a Democrat or Republican,” he says. He’s “right-leaning,” but doesn’t want to box himself in, he adds.

“If I had to, I’d say I’m a fiscal libertarian,” Kennington says. “You do whatever you want — it’s none of my business, and vice-versa.”

Kennington grew up in Texas in a conservative household. He listened to talk radio host Rush Limbaugh and used to wear a “Rush Is Right” T-shirt to school.

His work as a software engineer has taken him from Silicon Valley to Montreal to Cape Cod. “I’m very embarrassed to tell you that I’ve never voted in a presidential election,” Kennington says, adding that this year he plans to vote to set an example for his kids.

Kennington says he’s likely to vote for Trump, and that there’s “no chance” he’ll vote for Harris. He votes based on national security and the economy and thinks the growing national debt is “a recipe for empire failure” that neither party has “the guts to fix.”

On the international stage, he thinks the Biden administration has been too soft on foreign policy and that Trump might do better. “We need a strong, aggressive stance,” he says. “You need a bully to stand up to the other bullies.”

He has caveats about his own thoughts, though. “I don’t know what I don’t know,” he says, “and I feel unqualified to have these opinions.” He wants to do more research before making a final decision on his vote.

Kennington doesn’t talk national politics much with his neighbors, because “we talk about other stuff — like coyotes.” He knows his neighbors’ politics only if they post yard signs at election time, he says.

Kennington is an alternate on Eastham’s zoning board of appeals, and he noted that local issues can cut differently from national ones. “Since moving to Eastham, I’ve realized how much local political leadership and decision-making matters,” he says.

“On the local level, you start to lean left,” he adds. He thinks that some regulations can be good, and “on the zoning board, I think we should be protecting the natural environment.”

Kennington points out that between Texas, California, and Massachusetts, he’s never lived in a battleground in a presidential election.

“I’ve never lived in a state that was any kind of question,” he says, “so I’ve never been super politically engaged.” —Elias Duncan

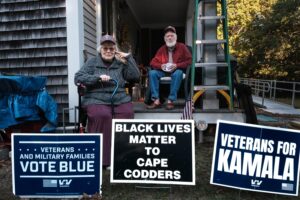

Veterans for Harris

Eastham veterans Kristina Meservey, 76, and Ross MacLean, 79, say they used to be Republicans — Meservey admired Massachusetts Sen. Ed Brooke, while MacLean was a fan of Teddy Roosevelt.

Meservey says her politics evolved after meeting rifle-bearing Ku Klux Klansmen at a 1968 rally for third-party presidential candidate George Wallace.

MacLean’s party switch came much later, in the 2008 election, when he decided that Republicans were out to raise taxes on “us lower-income folks” to pay for “tax breaks for millionaires.”

Nationwide, about two-thirds of veterans vote Republican, according to the Pew Research Center. Nonetheless, Meservey and MacLean believe their oath to the Constitution supports their decision to vote Democratic.

“Everybody in the military swore to defend the Constitution,” MacLean says. “Meanwhile, the Republican Party is screaming for a rewrite.”

Both Meservey and MacLean work for the Hyannis chapter of Disabled American Veterans, Meservey as commander and MacLean as adjutant. The organization is government-chartered and nonpolitical, but the pair hear plenty of political talk from the veterans it serves.

“Trump has been able to instill an absolute fear of immigrants,” MacLean says. “It proves just how unaware some people are.”

Meservey says there are a fair number of people she “rarely contacts” because of politics, including a bridesmaid from her first wedding whom she barely speaks to anymore. Other former friends refuse free health care from the Veterans Administration because of their “right-wing news bubble,” she says.

The pair have filled their yard with political signs, which Meservey says are sometimes stolen — especially the ones that suggest you can be both a veteran and a Democrat. “Whoever is taking the signs seems especially affronted by that message,” she says.

Both are worried about the upcoming election, especially given Trump’s impact on “perceptions of what is and isn’t truth,” they say. Because his false claims of winning in 2020 were so widely believed, “I won’t feel OK until Harris and Walz are certified,” Meservey says. —Parker Mumford

The Privilege of Voting

What Burchelle Edwards most wants to talk about is not which way he’ll vote but the way it feels to be preparing to vote for the first time. “It’s exciting,” he says.

Edwards grew up in Jamaica but has lived in Wellfleet for 14 years; he became a U.S. citizen in 2022. As a green card holder, “this was the one thing I didn’t get to do,” he says. “It’s a privilege to have a voice.”

He doesn’t talk with a lot of people about who he’s planning to vote for, but Edwards, 44, does talk about the candidates with his father, who is 78 and lives in Florida. The two don’t exactly agree.

“I tell him that I’m not decided and that there are some things I like about Trump,” Edwards says. “And he tries to enlighten me about history and tell me all the ways Trump will not be any good. My father is a Democrat.” Theirs are respectful conversations, though, not contentious. “We joke, even though maybe we’re both trying to provoke a little.”

What he likes about Trump is “the way he talks.” One concern Edwards has about Harris has to do with her career before she became a candidate. His complaint is not about her reputation as a tough prosecutor, however. It’s about not knowing what she stands for. “Her being tough is not a problem for me,” he says. “I like a woman who is tough.”

He works at Wellfleet Shellfish Company, the seafood wholesaler that, in spite of its name, is located in Eastham. Conversations aren’t especially political there, he says, though he hears a lot of encouraging talk about Trump from one co-worker. That colleague is “an American guy,” Edwards says.

Most of his friends in the Jamaican community lean Democrat, seeing that party as the “sensible, familiar” choice because its messages are similar to those of the social democrats in the People’s National Party in Jamaica. Jamaicans here don’t talk much about the election, he says, although there are no secrets: he knows “there are a few who will vote for Trump.”

Revisiting the idea of being undecided, Edwards says it’s not that he’s deeply torn. He just wants to go in on Nov. 5 and have the feeling of exercising “that privilege,” he says again, when he has the ballot in front of him.

“I want to make a choice that is not only good for me but also good for other people,” says Edwards. “Probably, that means going Democrat.” —Teresa Parker

Leaving the Party

Farrukh Najmi, 63, lives in Wellfleet and is an organizer of Wellfleet for Palestine. He’s always voted for Democrats, “but I may never again vote Democratic in my life,” he says.

He says he is voting for Green Party candidate Jill Stein because of “the Biden administration’s complicity in Israel’s genocide in Gaza.”

“As much as I am absolutely committed to seeing the Dems lose,” says Najmi, “I know that it will personally be a very difficult time for me. The way Trump is talking, I could be imprisoned or deported just for being a vocal activist for Palestinian freedom.”

Najmi has visited Wellfleet since 1980 and bought a house here in 2009. He moved here in July 2020 –– a goal he and his wife, Nancy, had shared for decades.

Wellfleet voted for Biden by about a four-to-one margin in 2020, and Najmi’s son and most of the people he knows are voting for Kamala Harris. This has made for some difficult conversations.

Najmi recently had dinner with a friend of 46 years who asked him what he thought of Harris. He hesitated, then said, “I think she’s evil.” By the end of that conversation, Najmi says, his friend said, “If you don’t agree with us, why don’t you leave our country?”

Other people have asked him when he’s receiving his check from Donald Trump, Najmi says. He says he would never vote for Trump, even though he wants to see Harris defeated.

“Some people’s argument is that Trump is going to be so much worse for LGBTQ and transgender people, minorities, immigrants, the environment,” says Najmi. “Where I don’t think he’ll be worse is on war.”

Najmi says he understands that people feel the stakes of this election are high — he himself is a “brown immigrant” from Pakistan, with a lot to lose under a Trump presidency, he says. “I just don’t think that our lives in America are any more precious than the lives in Gaza.”

Najmi expects that Harris will lose on Election Day, adding, “It will be because of their utter disregard for my vote and those of people like me.”

Until then, he’s trying to avoid confrontation with his friends and loved ones, staying “detached from the world” to minimize damage to “my relationships with the people I love.” —Dorothea Samaha