PROVINCETOWN — Four winter storms in the last seven years have pushed seawater across Commercial Street and into neighborhoods, inundating homes and businesses near town hall in 2018, along Howland Street in 2022, and around Suzanne’s Garden in December 2023 and January 2024.

In response, the town is creating a coastal resilience plan to assess neighborhoods’ vulnerabilities and provide a menu of options, including timelines and cost estimates for different strategies.

The planning effort kicked off with a public engagement event on the lawn of town hall on June 27; two more public sessions will be held in the fall and winter. The three companies that are developing the $300,000 plan — Scape Landscape Architecture, the Woods Hole Group, and Environmental Design and Research (EDR) — will present their results next spring.

The planning effort is modeled on Nantucket’s and was the first goal of the town’s Coastal Resiliency Advisory Committee when it began meeting in 2022. The plan will lay out near-term fixes and long-term approaches that town government and homeowners can adopt.

“We’re trying hard to get solutions that can be used within zero to five years,” said Russ Kleekamp, head engineer at EDR’s Hyannis office, to homeowner Jeanmarie Kaselau at the town hall event. “We have current needs now with flooding and bigger needs down the road, and we have to get the current needs addressed,” he said.

Kaselau’s house on Howland Street flooded in December 2022, and she has used sandbags to keep water out in subsequent storms. After the Jan. 13, 2024 storm, she bought plastic barriers that are held upright by sandbags and the weight of oncoming seawater to protect her property.

Kaselau asked Kleekamp if it were possible to add pumps to the town’s stormwater drains, which rely on gravity to carry water to the harbor and are impaired when the outfalls are under the water line, as happens during storm surges.

Kleekamp said that adding pumps to a municipal stormwater system is possible but expensive, and that state or federal funding would likely be needed.

Shedding light on that mix of public and private options — including how long they could take — is the goal of the plan, Kleekamp told the Independent.

“We’re looking at town-owned assets, but we’re also looking at inundation pathways in the neighborhoods and how you can try to solve those,” he said. “Some of the big flooding issues are on the flanks of the town where you don’t have municipal facilities but you have a lot of residents.”

Think Big, Start Small

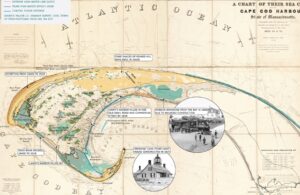

Maps on the town hall lawn showed that the town has had a shifting shoreline for centuries. The intersection of Snail Road and Commercial Street used to be the location of an inlet called Junky’s Harbor, according to an 1835 map, while the Herring Cove Beach parking lots are built on the former location of Lansy’s Harbor.

The Provincetown airport, which lies inside the historic footprint of Hatch’s Harbor, will be below the daily mean high water mark by 2050, according to another map. MacMillan Pier would be covered by a typical day’s highest tide by 2070, and a major storm could put Lopes Square under four to seven feet of water by then.

“I think these transects that show flood levels in relation to actual buildings are really instructive,” said advisory committee member Mark Adams. “Everybody who adapts now, such as by elevating a house, is going to have to adapt again later. It doesn’t stop.”

Committee chair Michelle Stefani said that adaptations like sea walls can also change the patterns of sand accretion on nearby beaches, which makes prediction more difficult. Even the town’s wave attenuator, which protects the fishing fleet on the east side of MacMillan Pier from storm damage, could be changing the sand accretion patterns at nearby Johnson Street Beach, Stefani said.

One goal of the public engagement sessions, according to Rikerrious Geter of Scape Landscape Architecture, is to gauge the public’s interest in various interventions.

“There’s a lot of appetite for maintaining the natural character of Provincetown using dunes, for example, but depending on the site, those can be washed away,” said Geter. “There won’t be one solution for every part of town.”

The town’s historic district is a unique complication because it is so large, Geter said. The consultant team had prepared a map that marked historic structures inside the town’s future floodplains but didn’t present it because “it was pretty much everything,” Geter said.

In the town’s most recent major storm on Jan. 13, it was town-provided sandbags that did much of the work of corralling the flooding. The dept. of public works had secured a sandbag-filling machine from Barnstable County and filled hundreds of sandbags for residents to carry away in their own vehicles before the storm.

A line of those sandbags along Commercial Street mostly blocked floodwaters from filling Daggett Lane that day — even though the water level in the harbor on Jan. 13 was almost a foot higher than during the storm that flooded Daggett Lane and Howland Street in 2022.

Those small-scale strategies are important, said Joe Famely of the Woods Hole Group.

“There may not be the capacity, either physically or monetarily, to knock down all flood risk in any of these places,” said Famely. “But I think there’s real value in exploring mitigation for properties that are highly exposed, and if we can help identify neighborhood-scale solutions, that would be a big help to the people who live there.”