PROVINCETOWN — This town has stuck out from the tip of Cape Cod like a sore thumb since at least the early 1900s, when Portuguese immigrants and an influx of artists suddenly made it unlike its more Puritan kin.

But Provincetown was unusual even before that. Its 1727 colonial charter failed to give the new town government the right to grant land to its settlers.

According to journalist Mary Heaton Vorse, the town’s dense and haphazard development was partly due to that lack of control. The 1727 charter is also the reason that the tidelands here are publicly owned.

Without the ability to grant land, Provincetown could not follow Truro, Wellfleet, and every other coastal town in the colony and grant ownership of its tidelands to coastal property owners.

Instead, from Howland Street, which was once Provincetown’s eastern border, to the breakwater in the West End, everything between the high and low tide lines belongs to the public.

The controlling high tide line is not the current one, however. It is the historic mean high water line from an 1848 map that defines where the Commonwealth tidelands begin. That map, given to the town by state regulators on Sept. 4, 1996, shows the high water line running right through major properties.

The line bisects the Crown & Anchor, Whaler’s Wharf, and Marine Specialties. It cuts through Seamen’s Bank and the post office, and it puts nearly all of the Provincetown Inn, the Surf Club, and the Lobster Pot on Commonwealth tidelands.

Public Land, Public License

According to Mass. General Law Chapter 91, private properties that sit on public tidelands are supposed to provide public benefits, to be negotiated and defined in special licenses.

The law was passed in 1866, but it was based on laws from the 1600s, said Jim Vincent, Provincetown’s DPW director and a former assistant chief at the state Waterways Division.

A series of coastal projects in Boston triggered major updates to the law in the 1980s, Vincent said. Stricter regulations were put in place in 1990, but an “amnesty” clause was included to allow property owners to apply to be regulated under the more generous regulations from 1984 instead of the 1990 codes.

Many of the people who applied for amnesty then think they have Chapter 91 licenses — but they don’t, Vincent said.

“There is a lot of confusion about this,” he said. “The 1984 regulations give people a little bit of a break if their structure is in the tidelands. As long as they’re not altering it or changing the use of it, then there are less public benefit requirements and an easier review process” under the older rules, Vincent said.

But all coastal properties that include tidelands are supposed to get a Chapter 91 license from the state whether or not they have “amnesty,” he said. About 60 privately owned properties in town have licenses, but about 80 more do not, town documents show. Of those, about 30 did not apply for amnesty in the early 1990s and would need to get their Chapter 91 licenses under the new, stricter rules.

The state can seek different kinds of public benefits depending on the nature of the property, Vincent said. The Chapter 91 license for Whaler’s Wharf requires the owners to maintain public bathrooms and to allow pedestrian access through its walkways to the beach, for example.

Properties with large parking lots that extend beyond today’s high tide line might be asked to provide stairs, Vincent said, so that beach walkers could pass over them at high tide without having to leave the beach and head to Commercial Street.

Some existing licenses require public pathways along the edges of properties so that pedestrians have more access points to the beach.

There is no current requirement for public access to the Provincetown Inn’s pool, Vincent confirmed — because there is actually no Chapter 91 license for the hotel at all.

The hotel’s developer, Chester Peck Jr., signed a Chapter 91 license to fill in four acres of Commonwealth tidelands in 1957 — and he secured a second license in 1960 to fill another 3.5 acres from the southernmost tip of the property to the Long Point dike. That work was never begun, and the second permit is now void, Vincent said.

The 1960 license does show the westernmost part of the hotel on a drawing. But there is no license specifically for the hotel or its pool, Vincent said.

“Only the Dept. of Environmental Protection can make a jurisdictional determination,” Vincent said. “I can’t tell you, the county registry of deeds can’t tell you, the town’s building department can’t tell you that you need a Chapter 91 license.”

According to the historic mean high water map, the entire Provincetown Inn is on the tidelands. “This property is going to need a license, in my opinion,” Vincent said.

A New Push for Licenses

Provincetown finalized its harbor plan in 2018, and in 2019 it was working with the state to get more Chapter 91 negotiations underway. The pandemic threw a wrench into that plan, Vincent said. The DEP has been concerned for decades that it doesn’t have enough staff to handle the number of licenses Provincetown will require, and that concern became more intense during the Covid shutdown.

“We’re trying to figure out an approach to educating everybody on what’s going on here,” Vincent said. “This is a conversation that has been going on — or been avoided — for 30-something years.” Vincent said the town is currently working to arrange a public meeting with DEP representatives in Provincetown this winter or spring.

Even completed licenses don’t always bear fruit quickly, however.

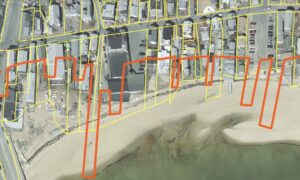

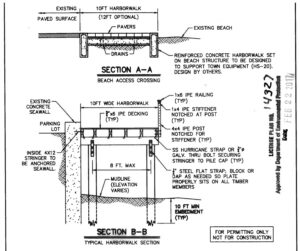

The owners of the Provincetown Marina signed a Chapter 91 license in February 2017 that included requirements for public bathrooms in the large building at the tip of the pier within two years. The license also required a 10-foot-wide public “harborwalk,” made of wood supported by pilings, that would run from the current sidewalk at Ryder Street all the way down the west side of the pier, around the southern tip, and up part of the east side.

According to the license, “all work authorized herein shall be completed within five years of the date of license issuance.” The construction period may be extended by the DEP in one-year increments after that.

This coming February will mark seven years since that license was signed. There are still no public bathrooms or harborwalk at the Provincetown Marina — just a sign that says, “No fishing from pier.”