PROVINCETOWN — At its annual tax classification hearing on Aug. 28, Provincetown’s select board voted unanimously to increase the town’s residential tax exemption to the legal maximum of 35 percent.

The residential exemption had previously been set at 25 percent of the assessed value of the average residential property here. That average is currently $1,061,331. At 25 percent, the exemption allowed one-fourth of that number — $265,833 — to be deducted from the assessed value of a residential property in calculating property taxes if that property was the primary domicile of its owners or of a year-round tenant.

Provincetown adopted the residential tax exemption in 2015, initially setting the amount at 20 percent of the average home’s value. The select board increased the exemption to 25 percent in 2017, and the town received permission from the state legislature in 2019 to extend the exemption to year-round rental properties.

Article 16 at this year’s spring town meeting expanded the residential tax exemption again, by allowing the owners of multi-family housing to claim one exemption for their own residence and another for year-round tenants living on the same property.

Citing a desire to encourage year-round rentals, the select board voted last week to increase the amount of the exemption to the maximum allowed by state law: 35 percent of the average assessed residential value here. That means that, for the current fiscal year, $372,166 can be deducted from the assessed value of any residential property that is also a full-time domicile — a deduction that is worth about $2,076 at the current tax rate of $5.58 per $1,000 of assessed value.

“One of the reasons why I wanted to revisit the residential tax exemption this year is to sweeten the pot and make it a little more attractive for somebody to consider renting year-round,” said select board chair Dave Abramson.

“The residential tax exemption is one of the most powerful tools that Beacon Hill has made available to us to put our policy where our mouths are in terms of supporting our residents and year-round residency,” said select board member Austin Miller. “I’ve heard some of the arguments against raising the residential exemption now, and I don’t necessarily find them compelling.”

Pat Miller, president of the Provincetown Part-Time Resident Taxpayers Association, spoke in the public comment period before the hearing, asking the board not to raise the exemption percentage. She provided a list of reasons, the first one being that the exemption has “no particular measure or check on whether those who ‘need help’ actually need the help, and those who are being asked to help can actually afford to help.”

Miller said that there are retired senior citizens who live here part-time and cannot afford the tax increase. She also said that the exemption is divisive and creates an “us versus them” mentality in town. (An op-ed essay by Miller appears on page A3 of this week’s Independent.)

The residential tax exemption was authorized by the state legislature in 1979. Because it is written to be “revenue neutral,” an amount equivalent to the property tax revenue that is not collected because of exemptions claimed by residents must be spread across all the rest of the taxed residential real estate. So, the overall tax rate goes up.

That raised this year’s tax rate from $5.32 per $1,000 of assessed value to $5.58, Provincetown Assessor Scott Fahle told the select board.

That new tax rate, about 4.9 percent higher than it otherwise would have been, is then applied to the taxable value of residents’ and nonresidents’ property alike.

This formula means that owners of higher-valued property get less benefit from the exemption, even if they claim it, because the remaining assessed value of their home is taxed at the new, higher rate.

A home worth $500,000 would see most of its tax bill wiped out by the $372,166 exemption, while a $3.6-million home would see a $571 benefit, if the owner chose to claim it, according to calculations Fahle provided to the select board.

The state Dept. of Revenue has a calculator online that shows the graduated effect of the residential tax exemption on the final tax bill of homes that claim it. As the assessed value goes up, the value of the exemption decreases relative to the added cost of the higher tax rate until it disappears altogether.

For nonresidents’ homes, the effect is simply to raise the tax rate from $5.32 to $5.58 — an added cost of $260 per year on a million-dollar home.

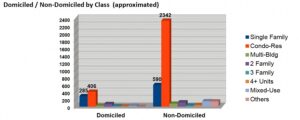

There are 3,471 residential properties in Provincetown that do not claim the residential tax exemption and 827 that do, according to Fahle.

One-third of the town’s single-family homes are expected to take the resident tax exemption this year, according to Fahle. Only 15 percent of the town’s 2,748 residential condominiums are expected to qualify — either because they are not their owners’ primary homes or because they are not rented out year-round.

Fahle said it was too soon to say whether the town’s expansion of the year-round tenant exemption to multi-family properties had caught on. “We’ll know more once we’ve had that in place for a year or so,” he said.

Fahle told the select board that he would implement whatever policy they chose, but the board of assessors had voted to recommend keeping the residential tax exemption at 25 percent.

“If you adjust it, we get some of the backlash,” Fahle said. “We don’t adopt it, we don’t vote it, but we are still the ones who get the phone calls.” Only two people work the phones in the assessors’ office, Fahle said.

“I’m sorry you’re fielding those phone calls,” said select board member Erik Borg. “Unfortunately, that’s not really a reason for me to not do the right thing.”

“Maybe we can avoid some of those calls” by making it clear that the rate increase was coming from the select board, not the assessors, Borg added.

Austin Miller said that “many of the same people who are concerned with additional tax burden” benefit from homestead exemptions on their primary residences in other states or from residential tax exemptions in other Massachusetts towns.

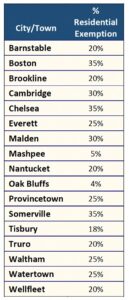

Cambridge and Malden have a 30-percent exemption, while Boston, Chelsea, and Somerville all have a 35-percent exemption, Miller said. (In fact, Watertown also has 30-percent exemption and Waltham’s is now 35 percent.)

When the select board came to the question of how much to increase the exemption, Abramson, Borg, and Miller all said they favored 35 percent, the legal maximum.

Board members John Golden and Leslie Sandberg said they were open to either 35 or 30 percent — “but if we went to 30, in another year we would be at 35,” said Golden.

That seemed to settle the matter, and the vote to raise the exemption to 35 percent was unanimous.