PROVINCETOWN — Zana Small, the first woman to register a motor vehicle in Truro. Alice Stiff, a former president of the Nautilus Club. The wives of a county commissioner, multiple Provincetown selectmen, and a school superintendent.

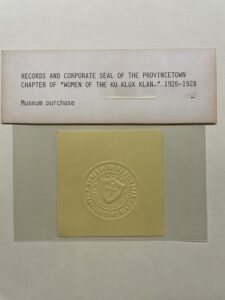

These and more than 100 other names appear on the 1927 membership rolls of the Women of the Ku Klux Klan of Provincetown, examined by the Independent with permission of K. David Weidner, executive director of the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum.

That the KKK was active on Cape Cod in the 1920s is no secret. Klan membership was surging throughout the country, including in New England, in the group’s second national reemergence. Contemporaneous — though perhaps unreliable — estimates from the Washington Post put Klan membership in Massachusetts at over 130,000 people, which would account for 10 percent of the state’s “native white” population at the time.

Though the hate group maintained its fundamental belief in white supremacy, the Klan in New England mainly targeted Catholics and immigrants, whom they saw as disrupting the white Protestant order. On the Cape, the influx of Portuguese fishermen fueled an animosity from the Klan at once ethnic, religious, and financial, according to local historian Lisa King.

“In Provincetown, there was this fear that the Portuguese population would outgrow the Anglo presence,” said Reinaldo Silva, a professor at the Universidade de Aveiro in Portugal and the author of a paper on the Provincetown Klan. In Provincetown, as in all of New England, the KKK’s activities were “a means to threaten or to scare these communities where they are immigrants, because they knew that they were mostly Catholic,” Silva said.

Local histories and newspaper archives show there were three active Klan chapters on the Cape, in Hyannis, Chatham, and Provincetown. They recruited hundreds of members, held large-scale events, and were responsible for several cross burnings, including possibly two near St. Peter the Apostle Catholic Church in Provincetown.

But the 1927 documents, whose contents have not previously been reported in detail, reveal that the Klan — at least in Provincetown — boasted within its ranks several affluent and influential citizens, many of them active in local and regional government.

The Outer Cape’s KKK members “were all the upper echelon” of Cape Cod society, said King, who reviewed the 1927 membership rolls and identified dozens of the women’s husbands. Klan members aimed to preserve the “old way,” King said. “They didn’t want any change.”

The Membership Rolls

A document titled “Kligrapp’s Quarterly Report” (the Kligrapp, in the Klan’s esoteric lingo, was a secretary) suggests that the Women of the Ku Klux Klan of Provincetown had 213 members in 1926.

By 1927, nearly 150 women had been suspended for not paying the Klan’s $10 annual dues (equivalent to about $175 today). Some may have been reinstated.

The roster lists the names and towns of over 130 current or former members. About 60 were based in Chatham, which had its own KKK chapter. At least 41 were from the Outer Cape: two from Eastham, three from Wellfleet, nine from Truro, and 27 from Provincetown.

The membership rolls likely represent just one year and leave many questions about the Klan’s operations unanswered. They reveal nothing concrete about the men associated with the Klan, who would have spearheaded its activities.

Nevertheless, the list of women — and their husbands, assembled by King through census records and town reports — provides clues about the Klan’s influence.

Edith Fogwell, née Woodland, was married to Jerome Fogwell, who served as superintendent of schools for Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown during much of the 1920s. Hattie Taylor, née Cobb, married Hersey Taylor, a Provincetown cemetery commissioner. Katherine Small, née Parker, married Ernest Hayes Small, a county commissioner.

The husbands of Lena Taylor and Elizabeth Manta, William Taylor and John Manta respectively, were selectmen and assessors in Provincetown. (Manta was the son of Joseph Manta, a prominent fisherman for whom a wharf was named.) And Elizabeth Chapman was married to George Chapman, Provincetown’s town clerk and treasurer from 1924 to 1930.

Edith, Hattie, Katherine, Lena, and both Elizabeths were all in the Klan.

Many Klan women were also members of the Nautilus Club, a social club King said was not open to Portuguese residents. According to historian Karen Krahulik, the KKK also shared members with the Research Club, a society dedicated to venerating Provincetown’s Pilgrim history. Several may have also been schoolteachers.

The precise extent of their husbands’ involvement in Klan activity is unclear. But King noted that married women would not have had the autonomy to join such an organization independently of their husbands.

“Women did not go out and join these kinds of groups without permission in the 1920s,” King said. “You couldn’t do anything without your husband.”

Many of the Klan members listed are sure to have descendants still living in the area. One is King herself, a Provincetown native of both Yankee and Portuguese heritage, who saw members of her Yankee family listed: Emma and Edwin Smith, Olive Williams, and Albert Burch.

“I don’t think it’s a reflection on any of us now,” King said. But, she added, “it’s disappointing to me that they would be involved in such a heinous group. To me, it’s vile. It’s so against everything I believe in.”

A Decade of Klan Activity

Historical documents suggest that thousands of Cape Codders were affiliated with the Klan, attending initiation ceremonies, public speeches, and several cross burnings.

The 1925 Provincetown town report says the fire dept. responded to a burning cross near the Provincetown standpipe on the evening of Aug. 11, near St. Peter’s Church. “The cross was fourteen feet tall and burned for some time,” the report stated. “It was a Klansman’s fiery cross.”

The following year, another cross was burned in front of St. Peter’s on Jan. 22, according to the 1926 town report. Next to it, a sign: “Vote for the right man” and signed “K.K.K,” according to the Yarmouth Register. The Klan denied responsibility for the incident, taking out an ad in the Provincetown Advocate offering $500 to anyone who could prove Klan involvement.

In Provincetown, the Klan was likely affiliated with the Center Methodist Church. It met at least once upstairs in the church during a service by minister Wilfred Hamilton, according to a document at the Provincetown Heritage Museum. When Hamilton left the church in April 1927, he charged the KKK with creating conflict in the congregation.

Author John Whiting wrote that his father came to Provincetown in 1937 to “unite the two Methodist churches.” He remembers “finding a box of old Klan pamphlets in the parsonage attic,” though he did not specify which Methodist church. Asked about the pamphlets, his father said he knew “the powder keg was still inflammable.”

In North Truro, the Klan met in a dance hall next to the home of George Dutra, who ran Dutra’s grocery and was North Truro’s unofficial mayor. A deputy sheriff and a Catholic, Dutra had a run-in with a uniformed Klan guard, whom he later determined to be responsible for cross burnings. “I caught him one day and told him I would hang him if he ever pulled a stunt like that again,” Dutra told the Register in 1970. “I told him, ‘You’re just following the leader. You don’t have any mind of your own.’ ”

In July 1925, “several prominent citizens” attended a Klan meeting in Barnstable, according to the Hyannis Patriot, which wrote that the Klan had organized “in a very quiet and orderly way” and praised its pursuit of “the preservation of law and order.” The following June, between 1,000 and 6,000 Klan members or affiliates attended a cross burning at Mill Hill in Yarmouth, where 200 new members were initiated.

In 1927, Klansmen rented Big Chief Dancehall in Wellfleet — near where Oliver’s Red Clay Tennis is now — for a speech by Guy Willis Holmes, a former minister from New Bedford who had been defrocked for his support of the Klan.

In August 1929, over 1,000 Klan affiliates attended a “Konklave” in Hyannis, according to an article in the Patriot. Among the “distinguished visitors” were “the Exalted Cyclops” of Klan units in Brockton, Boston, New Bedford, Chatham, and, notably, the Pilgrim Monument of Provincetown.

As the Klansmen enjoyed a “bean supper,” the Exalted Cyclops from Brockton described how “the Klan fills a great place in America and is a crusade for the perpetuation of true American principles which our forefathers left for us to carry on.”

Acts of Resistance

The presence of the Klan — and particularly the cross burnings near the church — left enough of a shadow in Provincetown to warrant a mention in Mary Heaton Vorse’s memoir Time and the Town.

“This act of intolerance was one of the greatest tragedies that had ever happened here,” Vorse wrote. “The dormant prejudice against foreigners awoke in this atmosphere of persecution.”

But rather than intimidate the Portuguese, the cross burning served to galvanize resistance to the Klan. The Knights of Columbus, a Catholic fraternal order, organized a three-day Fourth of July celebration “with a fair and fine fireworks,” Vorse wrote. And they organized politically, working to elect Catholic selectmen and hire Catholic schoolteachers.

“Instead of fighting back tooth and nail, they fought back with love,” said King, the local historian.

The Portuguese resistance to the KKK had mixed results, largely owing to the actions of Judge Walter Welsh, who was the grand knight of the Provincetown Knights of Columbus. Welsh served as a Massachusetts delegate to the 1924 Democratic National Convention, where New York Governor Al Smith, a Catholic, was vying with the Klan-backed William McAdoo for the nomination. Though the two sides settled for John Davis, a compromise candidate, Smith’s nomination four years later would drive the Klan in New England to support the Republican Party rather than the Democrats.

During the 1924 convention, a resolution was offered to add an anti-Klan plank to the party platform. But Welsh, himself decidedly anti-Klan, believed that “the best way to kill off the Ku Klux Klan is to ignore it completely,” according to the Yarmouth Register. He initially voted against the resolution on those grounds, and under intense pressure from other delegates, gave half his vote to the resolution.

The resolution failed by a fraction of a vote, and Welsh may have been the deciding factor.

The Historical Record

Often called an “invisible empire,” the KKK practiced intense secrecy using obscure jargon. Much like its white hoods, the Klan as an organization was designed to be opaque.

Though the 1927 membership rolls give a rare glimpse into the Klan, what is most striking is the near-total absence of information. In fact, those documents are “the only extant record of any Klan affiliation” on the Cape, said David W. Dunlap, curator of the Museum of the New York Times and author of Building Provincetown.

The archives of the Provincetown Advocate, the Outer Cape’s paper of record for much of the 20th century, are largely missing for the 1920s, when the Klan was active. No national Klan records have survived, according to SUNY Plattsburgh historian Mark Richard, who wrote a book on the KKK in New England.

Officials at historical societies in Hyannis, Orleans, Eastham, Yarmouth, and Wellfleet said they did not have any records in their collections relating to the Klan. The Truro Historical Society did not respond to a request for information.

“It is hard to delve too deeply because they were such a secretive organization, and a lot of the families who would have been associated with the Klan in the ’20s, many of whom were still present and around well into our own age, did not want history to record that,” Dunlap said. “At least politics has advanced far enough in America that membership in the Klan is not a source of pride.

“It’s a small town,” Dunlap added. “Memories, resentments, injuries, and traumas are long remembered, and they run deep. There may have been a sense of ‘That’s the past — let’s bury it,’ even while the tales of the cross burnings, at St. Peter’s particularly, resonated through the generations.”

For King, today’s politics demand a reckoning with the past. Indeed, the Cape’s Klan connection resurfaced in 1997 when a Hyannis man was found to be operating a Massachusetts KKK website, which he later took down.

More broadly, the far-right “Great Replacement” conspiracy theory — that political elites are facilitating the growth of marginalized racial groups at the expense of white people — strikingly mirrors the concerns at the core of Klan ideology in New England. King said she fears that adherents of that theory, like the Proud Boys, could one day come to Provincetown.

“Brushing the history under a rug is not acknowledging and dealing with it,” she said. The Cape’s Klansmen “are gone, they can’t be heard, but we can use it as a tool to learn from.”