TRURO — This town’s select board has joined Provincetown’s in objecting to the Request for Proposals the National Park Service issued on May 1 to invite bids on 10-year leases for eight of the 18 dune shacks in the Peaked Hill Bars Historic District.

As the Independent reported on May 11, the Park Service’s RFP ignores a years-long public process and the agency’s own signed agreements from 2012, which describe how lease solicitations should be written. The RFP omitted all of the selection criteria approved in 2012 by Cape Cod National Seashore Supt. George Price and Northeast Regional Director Dennis Reidenbach, and it includes an option to compete with other bidders by offering to pay more rent.

On May 22, Provincetown asked the Seashore to suspend the RFP, “redefine” it to include the 2012 agreement, and remove the option of bidding up the rental amount.

The select board also asked the Seashore to “reevaluate the impact of unprecedented seasonal restrictions which limit the occupancy of the dune shacks” to the period between Memorial Day and Labor Day.

On May 23, the Truro Select Board authorized the writing of a similar letter.

“How they’re handling this is an outrage,” said board member Bob Weinstein. “These shacks existed from day one for people who had no money, and to make money a requirement in an RFP is a violation of the cultural and artistic history of Truro and Provincetown.”

“This RFP is classist and reeks of a money grab,” said board member Stephanie Rein. She added that if new leaseholders did not understand the dune environment, they could “unwittingly cause irreparable damage” to the historic district.

The deadline for bidders is July 3. Because of the short timeframe, the select board authorized Weinstein and Rein to write and send a letter on behalf of the whole board without waiting for the board’s next meeting on June 13.

Select board member Sue Areson said she could reach out to “former colleagues in the media all over the country” to help publicize the letter once it is written.

Leasing Terms

By most accounts, the objections are not about whether the Park Service should offer long-term leases on the shacks but about how it should be done. More than a dozen public meetings from 2009 to 2011 were conducted on precisely that question. The Dune Shack Subcommittee of the Cape Cod National Seashore Advisory Commission wrote its report in 2010, and its recommendations were modified and then formalized in the Park Service’s official Dune Shack Historic District Preservation and Use Plan in 2012.

The Use Plan added five selection criteria to the Park Service’s standard leasing terms. They include knowledge of the surrounding environment; capacity to perform maintenance; commitment to public access; commitment to the “values of the historic district and the continuation of tradition”; and availability and intent to use the shack.

The plan also endorsed 20-year leases and the possibility of “hybrid uses,” in which dune shack leaseholders could allow artist-in-residence programs in the winter.

None of those terms are in the current RFP.

“I’m dumbfounded by this,” said Mildred Champlin, 92, who leases one of the few dune shacks that still in private hands and not part of the new re-leasing plan.

Champlin’s late husband, Nat, bought the Mission Bell shack before the National Seashore was created in 1961. Following an eminent domain lawsuit, the Park Service gave the Champlins a lease on Mission Bell for the lifetime of their children in lieu of payment for taking the property. Her three children now range from 54 to 63 years old.

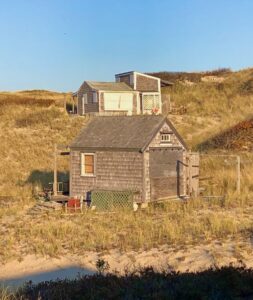

“The maintenance is endless,” said Champlin. “You have sand moving, covering the shack and then uncovering it. You shovel it out, or you shore it up. It’s constant.”

The work does not take place only in summer, Champlin said. Winter nor’easters are by far the most dangerous storms on the north-facing dunes of the backshore.

The blizzard of February 1978 that destroyed Henry Beston’s “Outermost House” in Eastham also scoured the backshore dune to within 12 feet of Mission Bell. “We had to pound holes in the icy sand to get fencing in front of the house,” Champlin said.

The nearby Adams shack had to be moved entirely that winter. Photos show it perched on the edge of the dune.

The ever-shifting sand accumulated until there were 100 feet of grassy “front yard” between Mission Bell and the dune’s edge, Champlin recalled. Then 75 feet vanished in one week during the so-called perfect storm of October 1991.

“We drive out to the shack at least once a month, even in winter,” she said. Even if leaks and wind damage were not a problem, simply managing the mice requires that much attention.

“There is nothing more disgusting, I can tell you from experience, than a mouse nest in a mattress,” Champlin said.

Mildred’s daughter Andrea said that it takes years to learn how to care for a shack and that neighbors offer critical support to each other.

“It takes a long, long time to learn how to live out there,” Andrea said. “We rely on each other. The thing about 10-year leases: by the time someone has figured out how to live out there, they’ll be thrown out.”

A Way of Life

Ever since the National Seashore was created, Park Service administrators have tried to exert control over the shacks and the people who occupy them — with varying degrees of success.

“The way they’ve dealt with the shacks is typical of all their patterns of management,” said John Thomas, a lawyer and musician who served on the Advisory Commission’s Dune Shack Subcommittee. There are good people working for the Seashore, Thomas added — but the imperative of national and regional leadership is to clear the land of challenges.

“Over time,” he said, “they narrow and reduce. The goal is to minimize all human activity except what they can carefully control.”

At the May 22 select board meeting, Thomas cited a mandate given to the Park Service by Congress to preserve the “way of life” on the Lower Cape.

“It’s in two years of Congressional hearings on the National Seashore, and it’s in the introduction to the Senate’s report of the bill,” Thomas said.

The second paragraph of that introduction reads: “The Lower Cape must also be viewed as a way of life — a culture — which though conditioned by its environment, finds its essence in the people who have lived and are living there. This bill seeks to preserve the way of life these people have established and maintained on the Cape.”