PROVINCETOWN — If you’re subscribed to emails from your town’s government, you’ve probably received a message recently asking you to respond to the Cape Cod Commission’s Regional Housing Preference Survey. The survey asks people across the Cape to rate various multifamily housing types and designs for how well they fit into the landscape and also offers participants maps of their hometowns where they can mark with blue circles where they think such housing would be most appropriate.

The survey is part of a much larger effort that spans the entire year, including public engagement sessions this summer and a draft regional housing strategy this fall. The strategy is being prepared with the help of contractors, according to Cape Cod Commission Executive Director Kristy Senatori, and will include a comprehensive look at housing strategies being used in other parts of the country and a menu of policy choices that towns can choose to adopt locally.

“Strategy identification is one of the main components of this,” said Senatori. “We’ve reviewed about 20 different plans from across the country so far, identified about 120 strategies, and we’re now working to narrow that field and put together a menu of options so that individual communities can decide what makes the most sense for them.”

Towns can expect to see model bylaws on that menu, Senatori said, as well as design guidelines that could help towns codify the look and feel they desire in new developments. Design guidelines also help builders know exactly what kinds of projects can meet with speedy approval — an important advantage when discretionary permits at planning and zoning boards can sometimes turn into years-long lawsuits.

Eastham’s residential zoning task force had wanted to develop design guidelines there, according to task force chair Mary Nee, but the project was too big to be completed by this year’s town meeting. This fall, the commission will be publishing a framework that any town can use as a starting point, Senatori said.

“We’ll be incorporating principles like net-zero emissions as well,” said Senatori, “so there’s an opportunity for communities that are interested to incorporate that into their design guidelines.”

Senatori wasn’t sure yet if short-rerm rental regulations would be in the mix. “There’s been a lot of discussion about short-term rentals, both internally and with stakeholders,” she said. “Those discussions are still ongoing, so I don’t have a solid recommendation to share with you yet.”

The work has already delivered at least one result, however. The Cape Cod Commission invited the housing directors of Vail, Colo. and Lake Tahoe, Calif. to its last conference in August 2022 to explain their year-round-occupancy deed restriction programs — a presentation the Independent reported on last year.

Provincetown, Nantucket, and the six towns on Martha’s Vineyard all put a version of that deed restriction onto their town warrants this year as home rule petitions — a first step toward copying Vail’s program, which uses special sales tax revenue to buy the restrictions, reserving hundreds of units for year-round occupancy rather than use as second homes.

The Bigger Picture

The Cape Cod Commission put out another housing report in 2017, a regional housing market analysis, that specifically called for follow-up actions such as the Housing Market Preference Survey. That survey is now online — in 2023.

The Independent asked Senatori about the pace of change and why a menu of housing strategies is being produced now, as opposed to five years ago.

“The housing crisis has risen to the top of our agenda, but it really can’t be looked at independently,” said Senatori. “It’s impossible to continue to build housing that isn’t supported by infrastructure. Whether it’s wastewater or transportation or low-lying roads or climate impacts, the Cape is made up of a series of systems, and we have to make sure that they’re all functioning.”

The commission has produced a series of major reports in recent years, including a Regional Policy Plan, an Economic Development Strategy, and a Climate Action Plan, Senatori said.

“Making sure that we have wastewater infrastructure is critical, and there’s been a lot of planning and implementation work there,” she added.

State Sen. Julian Cyr said that the commission has done a huge amount of work on wastewater issues — and that those problems were decades in the making.

“The commission has dedicated a tremendous amount of resources to figuring out the region-wide wastewater problem,” Cyr said. “Only 4 percent of Cape Cod is sewered, and the focus on wastewater was necessary and appropriate. Wastewater is key not only to stewarding our fragile environment but to building the denser housing that we need.

“The broader failure on wastewater dates back before the commission,” Cyr added, “to the ’70s and ’80s, when the federal government was offering to pay 90 percent for sewer systems under the Clean Water Act and our communities said no.

“That was a very conscious choice — municipalities and leaders were worried that wastewater infrastructure would lead to the overdevelopment of Cape Cod,” he said. “They opted for one-acre or two-acre zoning with Title 5 septic systems, and that really led to suburbanization and sprawl.”

The commission was created to control that sprawl. “They were essentially created to prevent development — housing wasn’t in their mission — and I think they’re pivoting to housing and they’ve been a helpful partner there,” Cyr said. “And they’ve been essential on wastewater.”

The Data Are Grim

An update to the 2017 Regional Housing Market Analysis is also coming soon, Senatori said. The data should be interesting — because the 2017 report was grim.

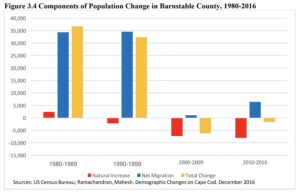

The population of nearly every town on Cape Cod stopped growing around 2003, according to the report. After decades of a growing economy and strong migration onto the Cape, both of those trends flatlined as well around 2000.

During the 1990s, about 12,000 housing units were added to Cape Cod, nearly all of which went to the year-round housing inventory, the report shows. From 2000 to 2015, more than 14,000 units were added — but nearly all of them went to the second home inventory. The county was losing year-round units when the report was written, and construction had slowed as well.

Finally, the county’s labor force, which had grown 16 percent during the ’90s, flatlined during the 2000s and then fell by 10 percent during the Great Recession.

The updated report is being produced by the UMass Donohue Institute. It should show how much Cape Cod has changed since 2017 — and how much has stayed the same.