PROVINCETOWN — At a rare joint meeting of the Provincetown and Truro select boards, leaders from both towns discussed the relationship between fresh water supply, future growth, and Truro’s Walsh property, which the town purchased in 2019 for $5.1 million. There is no immediate need for more water, according to Provincetown Water Dept. Director Cody Salisbury — but the Walsh property is an unusually good location for future wells, and at almost 70 acres it can support both long-term water needs and Truro’s current need for more housing, according to staff from both towns.

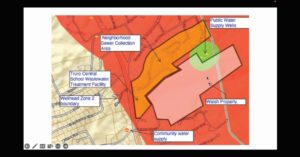

Salisbury presented a map that showed two future well sites at the east edge of the Walsh property, which he said would still leave plenty of room for other projects on the west side. Truro staff agreed and added some new details about the property’s potential for housing.

“Housing construction in Truro has not kept up with the needs that the town has — we’ve been underbuilding for decades,” said Town Planner Barbara Carboni. Truro intends to add about 200 units over the next 10 to 20 years, Carboni said, and the Walsh property is the “primary intended location” for that growth.

Truro Health Agent Emily Beebe offered an estimate of Truro’s future needs for municipal water that included 6,600 gallons per day for the 40 units at the Cloverleaf project and 33,000 gallons per day for “up to 200 dwellings” at the Walsh property. Other residential and commercial properties in North Truro also might want to connect to Provincetown’s municipal water lines, Beebe added, for a total estimate of an added 84,600 gallons per day.

Truro’s wastewater consultant, Scott Horsley, said that water quality at the wellfields could be improved from its current level, even with substantial new housing nearby, by hooking up those new units, the Truro Central School, and a few residential streets just north of the Walsh property to an advanced wastewater system. This same approach is being used at the 95 Lawrence Road housing development in Wellfleet, which Horsley also advised on.

There is at least one cesspool on North Union Field Road and another on Moses Way, according to Truro town records previously reported by the Independent. They are each about 500 yards from the North Union Field wellheads.

Truro Town Manager Darrin Tangeman said it would take five to seven years to develop new wellheads, so even though the need is not currently acute, the time to think about future supply is now.

Future Demand

Provincetown has contracted for a water demand forecast that includes the town’s underdeveloped and vacant lots as well as the potential for extra density that could be unlocked by the upgraded sewer system, Salisbury said.

“We’ve provided them with a rough estimate of a build-out — of how many more units could possibly be built based on underdeveloped and vacant parcels,” said Salisbury. That number is between 1,000 and 1,500 units, Salisbury said.

The sewer expansion is also relevant because under Title 5 rules the number of bedrooms on a parcel is tied to the overall area into which the septic system can leach wastewater. This bedrooms-per-acre formula governs much of Cape Cod’s built environment, but it no longer controls infill housing potential once sewering replaces septic systems.

How many homeowners would want to add bedrooms or accessory dwelling units is guesswork, Salisbury said, but the consultant will develop a range of forecasts of how much water Provincetown will need in the future.

At present, Provincetown is pumping about 80 percent of the capacity that is permitted by the state Dept. of Environmental Protection. That permit is for 850,000 gallons per day, averaged across an entire year. The town actually pumps around 1,300,000 gallons per day in July and only 400,000 gallons per day in February. The average across the year has been below 700,000 gallons per day in almost every year since 2010.

Meeting peak demand in the summer requires capacity well beyond the annual average numbers, however. The maximum capacity of all 11 of Provincetown’s wells together is about 1,800,000 gallons per day.

Salisbury also explained the town’s “unaccounted-for water” situation. The state requires towns to report how much water they withdraw and treat but then cannot bill to consumers because the water is lost in leaks along the way. The state likes to see at most a 10-percent loss rate, Salisbury said, but Provincetown’s has fluctuated between 10 and 30 percent over the last 12 years.

In normal soils like those in mainland Massachusetts, water that leaks underground eventually rises to the surface, Salisbury said. Cape Cod is an enormous sandbar, however, and water that leaks from pipes here simply sinks back into the sandy freshwater aquifer from which it came, making detection extremely difficult.

The town believes most leaks are in between the municipal lines and the individual meters on homes — that is, in the pipes that run underneath individual properties and sometimes underneath private roads.

“We have a lot of meter pits, which are meters located closer to the curb,” Salisbury told the select board. “We have looked at district zones, which are bulk meters throughout the system” that could narrow down where leaks are taking place, “but it’s a costly project — very costly,” Salisbury said. A cost-benefit analysis could show whether the recovered capacity would be worth the expense, Salisbury added.

Water Wars

Amid all this discussion of groundwater at the Walsh property, one name was conspicuously absent: hydrologist Thomas Cambareri, who was hired by the Truro Environmental Defense Fund to write a report about the importance of groundwater preservation at the site. Town staff did not include his report in the materials for the meeting. Cambareri himself did not attend, nor did any of the listed officers of the Truro Environmental Defense Fund.

Truro’s earlier study of the property, conducted by Tighe & Bond, said that Cape Cod Commission maps indicate that groundwater would be expected to flow from a groundwater ridge to the east of the site, in the National Seashore, to the southwest edge of the property.

Cambareri contested that conclusion in his August 2022 report and said that the intensive pumping at the North Union Field wells was enough to “draw down the top of the aquifer by well over 13 feet when pumping,” which would be enough to reverse the direction of groundwater flow across a large area, including the entire Walsh property.

Neither Scott Horsley, who made a presentation at the meeting, nor any other person either credited or refuted Cambareri’s claims. In fact, no one mentioned them at all.

Horsley instead emphasized that, by improving the wastewater treatment at Truro Central School and several residential streets north of the Walsh property, it would be possible “not only to offset the new development at the Walsh property but actually result in a water quality improvement.”

“As these plans develop, we’ll be able to refine our forecasts as to location, types, and density of housing,” said Carboni, “but we think this is an accurate forecast of what the town intends to bring online.”