PROVINCETOWN — There is still no monument to the indigenous Wampanoag people in the town where the Mayflower first dropped anchor. But that doesn’t mean there won’t ever be one. “I believe there is still interest in doing something,” Town Manager Alex Morse told the Independent. “It’s just a matter of identifying the time and resources to do it.”

The process of designing and commissioning a monument was initially focused on the Bas Relief Park on Bradford Street, the site of an enormous bronze sculpture that depicts the signing of the Mayflower Compact in Provincetown Harbor in 1620. Smaller markers list the people aboard the ship and the text of the Compact, but nothing at the site mentions the Native people who, when the English Separatists landed, already lived on the Outer Cape in a year-round settlement at what is now Eastham and seasonal settlements throughout the region.

The absence of a marker was becoming acutely obvious in the years leading up to 2020, when celebrations were being planned for the 400th anniversary of the Mayflower’s arrival. The Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum was working on a complete overhaul of its presentation of the events of 1620 during those years, according to Executive Director David Weidner. (See related story)

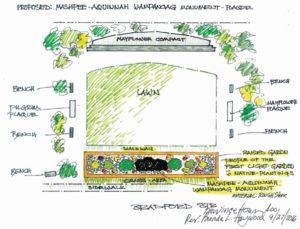

In September 2016, local civil rights leader and minister Brenda Haywood brought a proposal to the town from several Wampanoag cultural leaders, including three who were advising the Pilgrim Monument — Linda Coombs, Paula Peters, and Jim Peters. That proposal was for a black granite marker and garden along the sidewalk at Bradford Street, placed so that it would be indelibly present yet still not obscure the larger and higher brass sculpture behind it.

A landscape architect developed a site design in 2018, and the town held public hearings in January and March 2019. By late 2019, however, conversations between the town and the proponents had broken down.

“The parties who were participating are no longer communicating with us,” then-select board member Lise King told her fellow board members in October of that year.

People who witnessed the breakdown said it was difficult. The Wampanoag leaders did not feel respected, Weidner said. King worried aloud at select board meetings that there would not be enough votes for their design to pass. Then-select board member Cheryl Andrews suggested alternate approaches, such as a life-size sculpture at the Pilgrims’ First Landing Park in the West End rotary, but that location did not come across as an adequate substitute for the Bas Relief Park.

The select board voted to bring in a consultant to help reset the process, preferably someone with extensive experience in indigenous representation, municipal procurement law, and public art. The town received a bid from Jennifer Himmelreich, a director of the Native American Fellowship program at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem. Himmelreich came with a personal recommendation from Joe Horse Capture, curator of Native American History at the Smithsonian, King said. A $12,607 contract with Himmelreich was approved at a town meeting in September 2020.

A health crisis in Himmelreich’s family forced her to turn down the contract, however. The $12,607 was never spent. In the midst of the Covid crisis, and with the 400th anniversary celebrations all canceled anyway, the problem of Wampanoag representation lost its place atop the town’s agenda.

“It’s not that it couldn’t happen,” said Michelle Jarusiewicz, the town’s housing specialist, who had been tasked with organizing stakeholder discussions around the Bas Relief restoration project and the proposed Wampanoag memorial.

The imbalance at the Bas Relief Park isn’t going away, Jarusiewicz said — the enormous monument to white colonists still has no counterpoint that acknowledges Native people.

“It got tabled, but it’s not impossible,” Jarusiewicz said. “Other communities do it. It’s just tricky.”