WELLFLEET — The conservation commission has again denied permission for the construction of a 241-foot rock revetment in front of the Blasch house on Chequessett Neck Road.

The 5,817-square-foot house, built in 2010, is now 12 to 14 feet from the edge of an eroding coastal bank just north of “the Gut,” the narrow strip of sand and marsh separating Wellfleet Harbor from Cape Cod Bay. The latest action came on Feb. 17 at a court-ordered remand hearing.

As reported by the Independent on Dec. 24, in the last two years the coastal bank has lost six to seven feet per year and the house is at grave risk of collapsing. Its owners appealed the commission’s December 2018 rejection of the seawall plan in Barnstable Superior Court, where it remained in litigation until last week.

The Feb. 17 vote was 5-0. The commission cited three reasons for the denial: first, that the owners did not effectively explore alternatives to the seawall; second, that the commission “did not have the chance to thoroughly look at the evidence around the consequences” of constructing the seawall; and third, that feasible alternative solutions do exist, including demolishing the house and rebuilding farther from the edge of the bank.

The Feb. 17 vote was 5-0. The commission cited three reasons for the denial: first, that the owners did not effectively explore alternatives to the seawall; second, that the commission “did not have the chance to thoroughly look at the evidence around the consequences” of constructing the seawall; and third, that feasible alternative solutions do exist, including demolishing the house and rebuilding farther from the edge of the bank.

The seawall proposal has been vigorously opposed by officials of the Cape Cod National Seashore, in which the house is located.

In comments delivered at the hearing, Seashore Supt. Brian Carlstrom again urged the commission to deny the permit and called the design of the house itself “flawed and deficient.”

“We believe the applicant’s need for a solution to the natural coastal bank erosion is directly attributable to the architectural engineering of the house piling foundation, which design is uniquely high-risk and apparently inadvisable in this type of vulnerable coastal bank location,” Carlstrom said. “We continue to believe that solutions such as the routine replacement of the coir envelopes or retreat to a new house location should be considered, as is widely practiced on Cape Cod, particularly given this is such an important and prominent location within the national park area.”

Commissioner John Portnoy, who was traveling and unable to attend the hearing, submitted a written comment.

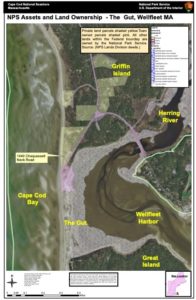

“I think it’s highly relevant that the proposed hard coastal structure would be the only impediment to natural coastal processes from Jeremy Point to Pamet Harbor — a distance of eight miles,” Portnoy wrote. “Undisturbed shorelines of this extent, second only to the 40-mile backshore of the Cape, are extremely rare throughout the nation and even the world. Further, the Gut, Griffin Island, and Great Island are within a national park, lands held in trust by the U.S. government for the enjoyment of all citizens. The proposed hard structure will permanently compromise public values and public access associated with National Seashore resources appreciated by thousands of people every year.”

On Dec. 2, the urgency of the erosion prompted the owners to request emergency certification from the commission for a “soft solution,” involving installation of three biodegradable coir (coconut fiber) cylindrical envelopes filled with sand — essentially, giant sandbags.

On Feb. 17, before the remand hearing, the commission approved an order of conditions for the “soft solution,” including regular monitoring of the envelopes. Despite losing some sand in an early February nor’easter, the sand-filled envelopes, which typically last from two and a half to three years, are doing their job and “continue to be in good shape,” according to Seth Wilkinson, who installed them.

In the original application submitted by the trust that owns the Blasch house in September 2018, the alternatives analysis did not include the sand-filled envelopes, noted Commissioner Michael Fisher. Therefore, the application was incomplete, and the sand-filled envelopes should be considered a feasible alternative, he said.

Moving the house is the only logical solution to the problem, said Commissioner John Cumbler.

Commissioner Barbara Brennessel agreed.

“Long-term, this house should probably be moved,” she said, “if the owners want to enjoy the property.” But in the short term, said Brennessel, the current alternative structure in place — the sand-filled envelopes — should continue to be monitored.

Commission Chair Deborah Freeman agreed that “it is functioning and protecting the bank.” Freeman said, “This indicates that there is another solution — or at least one that has to be looked at and tried.”

The virtual hearing was attended by nearly 30 people, many of whom were adamantly opposed to the seawall.

Referring to the findings of technical reports prepared for the National Park Service, Carlstrom said, “We have previously raised eight points of concern, which remain unaddressed by this proposal.” Among those concerns, he said, was the applicant’s failure to address “end scour and other impacts on the Gut and Great Island.”

“End scour” refers to the removal of underwater material by waves and currents, especially at the base or toe of a shore structure, according to the Mass. Barrier Beach Task Force.

According to the findings of the commission in 2018, installing the seawall “is likely to lead to significant erosion on abutting properties — the land to the south is a sand dune which protects Wellfleet harbor,” said conservation agent Hillary Greenberg-Lemos. The evidence provided by the Park Service — in the form of technical reports — supports those findings, she said.

The decision to deny the notice of intent for a seawall will be drafted, reviewed at the next conservation commission meeting on March 3, and then filed, said Town Counsel Amy Kwessel.