PROVINCETOWN — Testing wastewater for Covid was an unproved idea at the start of this pandemic. If it worked, it would be a way to cheaply test entire communities at once, because everyone connected to the sewer system makes a “contribution” to it, every single day. No one could say how meaningful the data would be, though: if they jump around too wildly from reading to reading, then there’s no pattern to discern, and not much to be gained.

Months of wastewater test results from Boston, Nantucket, and Provincetown show that, while the data are indeed jumpy, they can still send clear signals, especially when things are going bad. Health directors in Nantucket and Provincetown have relied on wastewater data to warn their populations of coming trouble.

In Nantucket, three different surges in discovered cases were preceded by spikes in wastewater testing data. In Provincetown, no cases have been discovered since early November, but a significant spike in wastewater data led the health dept. to warn residents that “the virus is present in our community.”

Ain’t Easy Being Small

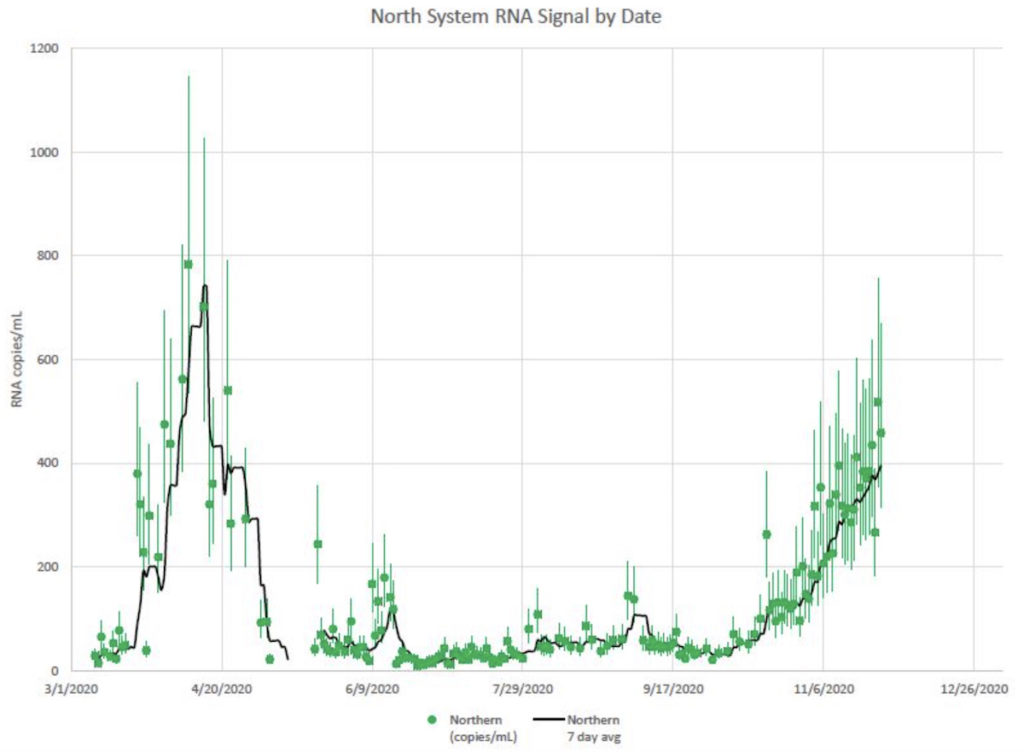

Boston started testing its wastewater extremely early in the pandemic, on March 9. Its data include the March-April wave in Boston and then a long period of very low results from June to August.

From a data standpoint, having both kinds of result is extremely valuable — it’s clear what kind of numbers would correspond to a wave of real cases. When Boston’s wastewater numbers began to rise after Oct. 18, and then dramatically accelerate in November, no one doubted that the numbers indicated something real.

For smaller communities, though, it’s not that simple. Nantucket started testing wastewater at its Surfside treatment facility in April. Provincetown started testing in August. There were hardly any active cases in either town when testing started. Most of the early results were “below the threshold of detection.”

When positive results did exist, it wasn’t clear what they meant. The test can’t distinguish between dead and living virus, nor can it distinguish between day-trippers and residents. Nor was it clear what 2 or 5 or 10 real cases would look like. Would they escape detection entirely, or would they be off the charts?

“It doesn’t always extrapolate to small numbers the same way,” said Nantucket Health Director Roberto Santamaria. “You get noisier results with small numbers.”

Even in the summer lull, Boston had hundreds of active cases at a time. When it comes to sampling, hundreds is a much easier number to work with than single digits.

Noise, Then a Signal

Nantucket went through a major Covid outbreak that began in late June and accelerated in September. According to Santamaria, wastewater testing was a leading indicator that allowed him to alert the island to danger before cases were actually discovered by individual testing.

“It doesn’t tell us an exact number” of upcoming cases, said Santamaria, “but it does give us time to be proactive. When we see that spike coming, we reach out to the Chamber of Commerce, the builders and landscapers associations, and try to create hypervigilance. I’ll do videos in English and Spanish and push those out to the community through Facebook and the newspaper.”

The Independent reviewed the timing of individual positive test results and wastewater testing on Nantucket. A wastewater spike on June 8, when there were no identified active cases on the island, may have foreshadowed the eight cases that were discovered in the last week of June. Another spike on Aug. 31 may have been an early sign of the 30 cases that were found in the second week of September.

The data are noisy; it’s hard to say for certain that these test results correlate to these cases. An unmistakable signal appeared, however, in tests on Oct. 19 and Nov. 2 and 10. The number of virus copies per milliliter of wastewater went to three times, then 10 times, and then 12 times the prior record. From June through September, the highest readings had been 38 copies per mL. By Nov. 10 it was 463 copies per mL.

Even in a noisy data set, when something goes up tenfold and stays there, that’s a signal. Nantucket has identified more than 110 new cases since Oct. 19. That’s 40 percent of all the cases that have ever been found there.

A Warning in Provincetown

Provincetown uses a different company for wastewater testing than Nantucket, but the data show the same basic patterns. There was one early outlier, some bouncing around at relatively low levels, and 10 tests that showed no results at all. Then, results from Nov. 8 and 10 appeared (Provincetown tests on Sundays and Tuesdays to try to account for weekend and weekday occupancy.) The Sunday test was 15 times the average of the prior four weeks: 274 copies per mL. The Tuesday test was 108 copies per mL, or six times the prior average.

Based on that, the health dept. notified the public: “Although there are currently no positive cases in Provincetown, the latest results of the town’s wastewater system reveal an upward trend which indicates the virus is present in our community. Some people in town are carrying the virus. We ask that everyone be especially cautious.”

That statement was dated Nov. 18, and there still were no detected cases in town as of Nov. 30. Wastewater testing picked up a signal that testing of symptomatic people still hasn’t confirmed.

“For us, it’s another measure to try to understand what’s going on in the community,” said Provincetown Health Director Morgan Clark. “I really want people to observe all of these precautions all the time, not just when we are posting case numbers, or viral loads in the wastewater.”

Provincetown receives the wastewater readings about a week after samples are taken. “Even with a lag in the data, we are still getting a heads up on what’s out there,” said Clark. “Also, we could be getting a heads up that someone who was here last weekend is now gone, and getting symptomatic somewhere else. I’m not going to make the assumption that viral load in our wastewater is actually from people who live here.”

Provincetown’s sewer system covers only about half the town, but that includes nearly all the tourism businesses on Commercial Street.

“We’re looking at the science behind the septic testing that some colleges are trying at the level of individual dormitories,” said Clark. “It’s really experimental, with volumes that small. But we are looking into it, because the school isn’t on the sewer system, and I would really like to get the best information possible to protect our school.”

According to state Sen. Julian Cyr, 96 percent of Cape Cod is on septic systems, not sewers. But schools, nursing homes, churches, and many large workplaces could potentially use septic testing, if it is proved to work.

Wastewater testing isn’t expensive. Nantucket is paying $1,500 per sample, or about the cost of 10 individual Covid tests. Provincetown’s tests are through a joint venture between Columbia University and the private company AECOM, and cost $550 each. Organizations such as schools could someday find frequent wastewater testing to be significantly cheaper than widespread individual testing.

Towns, however, have the extra benefit of a professional DPW staff. The real barrier to widespread septic testing may not be the cost — it may be finding enough plumbers to do the job.