There is a meadow in Eastham just off the side of the highway that pulls my attention every time I pass by. The field is the site of the old T-Time driving range, which was purchased by the town. For the last few years, the site has been allowed to go wild.

In the summer, coreopsis and dandelions wave gold and yellow. Bunny grass is heavy with iridescent seedheads. Queen Anne’s lace, every flower a tiny galaxy, drifts in the breeze. Each season of this field has its star, but from midsummer to deepest winter, the shimmering copper and violet-blue stalks of little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) combine with silver seedheads to grace the stage most spectacularly.

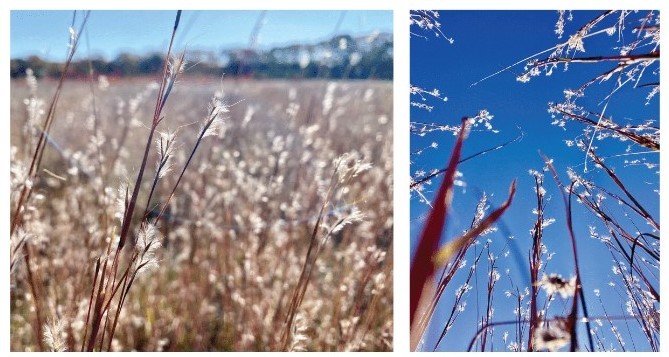

On a recent sunny day, I went to the meadow to closely observe the bluestem in autumn. The wind was light but carried with it a sharp chill from the north. The sun was at its highest point in an open sky, shining down with warmth that reminded me of the last days of summer. Two red-tailed hawks rode the wind.

I wanted to sit with the little bluestem and really see it. Every time I do this — stop, sit, look closely, roll back the layers, and see what’s in front of me — it makes me wonder if I’ve ever looked at anything closely enough.

Settled on the warm ground, I pulled a stem from a tuft of curled, dry ribbon —and laid it in my hand. Starting at the bottom, I ran my fingers and eyes over its length, peeling away old, dried blades, exposing a vibrant palette of color. The part of the stem closest to the ground holds a tender spring green that fades to the dusty purplish-blue from which the plant gets its name. The first node, the structural knuckle in the grass stem, is a glossy seam of the same hue. The next length of stem grows paler toward the top, at which point it emerges a brilliant magenta, then another glossy node, another length of slate, then sunrise red.

The genus name of the plant, Schizachyrium, derives from two Greek words meaning “chaff” and “to split.” At each node, a thin wiry shoot breaks away from the main stem, emerging from a curled protective blade. As the stems multiply, the size of each stalk broadens, and so the form of the entire plant expands from its narrow base to a wide crown. Scoparium, the species name, means broom-like.

Dark, narrow seeds alternate toward the end of each stem. The seeds have two little arced wings of downy fluff at the point at which they are held to the stem, like tiny moths emerging from a host plant with wings too fresh to fly. They will lift the seeds from the mother plants when the soil, the sun, the rain, and the wind say it is time.

All the vivid colors of the bluestem are there for those who look closely this time of year. A field of bluestem reminds me of a body of water on an overcast day reflecting all the tones of the undersides of moody clouds above: steel, bronze, copper, blue, purple, silver, and gold, waving in rolling gusts. Above this rich metallic field, the fluffy mist of seeds is held gently, catching the low angled rays of the autumn sun. Each glowing bit of light, each tiny seed, is a future life held aloft to the world, a spark entrusted to the wind.