ORLEANS — Arin Hirst calls his greens-growing business “Sketchy Greenhouse,” in honor of the formerly dilapidated state of Putnam Farm in Orleans, where he and his friends hung out when they were in high school. He graduated from Nauset Regional High in 2008.

The land, which had been farmed for centuries, was named Putnam Farm after the family who owned it in the 1950s. The place became derelict in the 1990s, but since its 14.2 acres were bought for restoration and conservation by the town of Orleans in 2011, Putnam provides land where several farmers including Hirst now work.

His name was pulled in the original lottery for the first five plots in 2018, which is also when Hirst began selling his crops at farmers markets. As of last January, the town was leasing 12 active 3,500-square-foot plots to local farmers, with eight more in the works.

Hirst’s salad greens, which pack his little plot at Putnam, and his foraged goods — in summer, blueberries and beach plums — are a hit at the Orleans, Wellfleet, Truro, and Provincetown farmers markets. But he didn’t come from a farming family, he says. “I got into farming in kind of a nontraditional way,” says Hirst.

A three-month internship at the Green String Institute’s 140-acre farm in Petaluma, Calif. is what got Hirst interested in farming. (The farm and institute began an indefinite pause at the end of 2022 for lack of farm staff, according to news reports.) Hirst was there the summer before his senior year at UMass Amherst, where he studied social thought and political economy; he graduated in 2014.

Bob Cannard was the program leader at Green String and became Hirst’s mentor. Cannard, he says, is “the reason I got really good at growing a lot of plants really efficiently, really fast, in a very natural way.” Cannard’s approach to plant propagation from the nursery-business end of the operation got Hirst’s attention. “His whole philosophy of natural process agriculture is something I still adhere pretty strongly to,” says Hirst.

That philosophy is focused more on stewardship than on production, Hirst says, and its main tenets include cultivating “50 percent for humans and 50 percent for nature: as you’re farming, you’re trying to give back to the land as much as you’re taking from it.” In practical terms, Hirst says, this means letting plants live out their full life cycles: “Let things go to seed, let leaves come up, let all the plants that want to grow there anyway form their own balanced ecosystem.

“It’s not as high yield a system as conventional agriculture, where you’re just pumping nitrogen in to try and get the biggest yield,” says Hirst. “But you get this balance where no one insect or weed can have a population boom.”

But it’s a philosophy easier said than done, especially since Hirst doesn’t manage his own land. Nor does he own any. He has two growing spots: he grows microgreens in a greenhouse next to the apartment he rents in Truro and salad greens at Putnam Farm.

Land management questions are further complicated, he says, by the fact that Putnam Farm was purchased by the town with a Local Acquisitions for Natural Diversity (or LAND) grant that is primarily geared toward conservation and passive recreation, not productive farming, and is managed by the Orleans Conservation Trust. That means there’s “a lot of ambiguity about how much agriculture can actually happen there.”

For growers like Hirst, the arrangement creates a clash between the aesthetics of a recreational spot and the unsightly realities of the farm work that goes on there. “There’s been an issue with us trying to build infrastructure, like a wash-pack station, storage sheds, and food-storage refrigeration,” says Hirst.

Scenes of farming, he says, don’t always align with the priorities of passersby, he says. “Farming requires a lot of materials and equipment that aren’t what people who just want to passively enjoy nature want to look at,” says Hirst, who adds that he’s been “written up for having my beds be too weedy and having my crops go to flower and not being productive enough.”

To Hirst, the shagginess is desirable, an aspect of his Green String philosophy. But nonfarmers, he says, “don’t have a gauge for how fast plants grow or how hairy you can let your farm get before you have to mow it back.”

Of course, things would be easier for Hirst if he had his own land. But that isn’t the solution he’s looking for. “I would much rather put efforts into changing public policies,” he says. His dream would be to create ways for communities to use vacant public land — land not designated for conservation — to grow food.

Another reason why policy change is more important to Hirst than personal land possession is that he sees potential for a more cohesive approach to conservation and farming. Rather than today’s haphazard patchwork of conservation spots that create mini ecosystems and make it harder for beneficial insects and animals to inhabit the land, he envisions “a network of semi-wild, semi-cultivated landscapes that are all interconnected.”

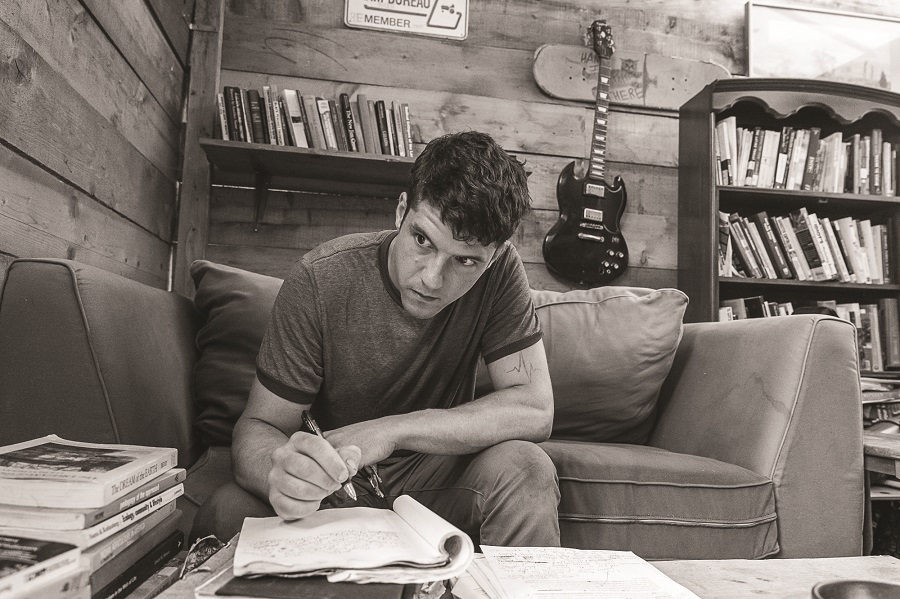

Hirst’s passion, beyond growing, is advocating for those kinds of changes. “I was going to a lot of agricultural council meetings in Orleans,” he says, and “I’ve been in discussion with people at Sustainable CAPE about blueberry forest ideas.” And for the past three years, Hirst has been working on a book that blends his experience as a “food system worker” with his thoughts on changing land use policies, supply chain infrastructure, and housing systems.

Meanwhile, Hirst believes that consumers supporting farmers by buying local is still a step in the right direction. “If you can get blueberries from this plot of land,” he says, sweeping a hand across the green fields of Putnam Farm, “that one package of blueberries is one box that you don’t have to buy from a plantation” — and have trucked in from a distance.

Hirst worries about whether there’s a future for the Cape’s growers. “A lot of young farmers have left,” he says. “A lot want to get out and give up.”

He doesn’t want to do that. Instead, by sheer necessity, he puts his bigger projects on a back burner. “I have to split the difference between how much I want to save the world and how much I want to just survive,” he says.

He gets by on farming, Hirst says, but barely. The same is true, he says, for most people who farm on Cape Cod: “A lot of us still have student loans. None of us have retirement plans. Rent is easily more than half of what we spend our yearly income on.

“We as a society have priced ourselves out of being able to feed ourselves,” Hirst says. It’s a reality he sees as “kind of the most ridiculous thing you can think of.”