Text and Drawings by Abraham Storer

Dave DeWitt has been working the same plot of land in the Truro woods since 1987, starting when it was a heather farm, Rock Spray Nursery. He worked there for 13 years before taking over the production, adding greenhouses and growing a range of crops, most notably salad greens, from which his business derived its name, Dave’s Greens.

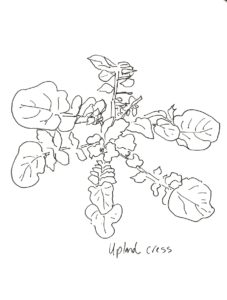

“I’m known for my salad greens and my tomatoes,” says DeWitt, whose salad mix contains up to 27 different varieties. “It’s not a lettuce salad mix,” he says, “it’s an everything else salad mix.” It includes brassicas, Asian greens, herbs, and edible flowers.

He sells his produce locally at restaurants, farmers markets, through a CSA, and at the end of his driveway on Holsbery Road in Truro. In late February, he was working with Arin Hirst, one of his small crew, patching up the greenhouses to prepare them for this year’s crops.

Q: How do you use greenhouses in your production?

I start planting seeds on March first. I used to start in February, but then I need a lot more heat, and a lot more fuel. Getting things to germinate and getting the little seeds started and the cuttings going requires heat. I keep it probably at 50° F for the tomatoes and everything. It could get up to 90° F in the greenhouse in March if the sun is out and the doors are all shut.

After planting the seeds, it will take two weeks for the greens to grow. Then we’ll plant them in grow bags — these are large fabric containers, useful because they’re portable — in another greenhouse, usually unheated. Two or three weeks after that we’ll be harvesting. The greens are about a 30- to 40-day crop. Then we do succession plantings throughout the whole season. We just keep reseeding, harvesting, planting.

Q: When does your harvest end?

Our last big harvest was two weeks after Thanksgiving. Sometimes I keep things going for my winter harvest, but I don’t keep my greenhouses heated all winter. This year I didn’t keep the greenhouses going. We have so much cleanup work and physical work to do around here that we decided to forego harvesting for winter markets.

Q: If you wanted to keep things growing in the winter, what would you do?

I would make sure all the doors are closed and all the greenhouses are tight to the weather. If I do that, I can grow salad greens all winter long — they will grow at freezing or slightly under. Once you get below 27° or 28° F, especially if it’s windy, the weather will kill them.

There are a lot of ways to grow greens all winter here on the Cape without heat. Spinach and arugula are probably the two easiest to succeed with, but you can also grow many Asian greens in winter in small greenhouses, cold frames, or under floating row covers. There are a lot of different techniques, but it’s all about timing. The main thing is, you have to be ready to go in September. That’s why I teach a class on winter gardening at the Truro Public Library in August.

Q: What is the timing, say, for winter arugula or spinach?

Start with seeds the second week of August. You need to be able to plant out seedlings during the first two weeks of September, so they have enough warmth and heat to get a strong root system. If you don’t have a strong root system going into the winter, when you harvest something it won’t regrow. If you get a strong root system developed, you can come back every 5 or 10 days and harvest more — cut and come again.

Then, when it’s really cold, you can make what’s called a caterpillar tunnel. It’s just metal wires formed into hoops that enclose the beds in a half circle. You can cover that with plastic or floating row covers to extend your season. It’s actually harder to grow salad greens in the summer: they go to flower if you’re not doing succession planting and keeping a harvest schedule. The beauty of the winter is you can harvest whenever you feel like it — the greens will just sit there.

Q: What’s your advice on using grow bags?

If you’re going to have biologically active soil, you need your containers to be 50 gallons or larger in size. When it comes to container gardening, that’s where people tend to fail. If you’re just using potting soil and fertilizer, it’s a way of growing, but if you’re relying on the bacteria and the fungi to make the nutrients available for the plant, like in nature, then you need a certain amount of biomass to be able to support life. That’s the idea behind Korean natural farming.

Q: What is Korean natural farming?

It’s a way of bringing indigenous microorganisms into the soil to get the soil back to balance, the way it’s supposed to be. Cho Han-Kyu, known as Master Cho, is the person who created this type of farming. A student of his, Chris Trump, who has a macadamia farm in Hawaii, is my teacher. I took a class with him four years ago and turned this farm over to Korean natural farming after I first met him. He will do an intensive five-day course here in April.

We capture microorganisms, grow them out, and then add them to our soil. You need to taste and smell things, so you really need to be taught how to do it — there’s a lot of fermenting going on.

If you have biologically active soil, or living soil, then you don’t have to worry about managing pH for the nutrients plants need to get freed up from the minerals that are in the soil. That’s the goal of Korean natural farming.

I don’t have to fertilize anymore. I’m saving thousands of dollars because the indigenous microbes are doing the work. Pest and disease pressures are getting fewer and fewer. In the greenhouse, the vibrancy of the plants was noticeable year one. In the field it takes a little more time. It takes a good five to eight years to get your soil back in balance.