January is the hinge of the garden year. With the garlic long planted and my tools cleaned and sharpened, I look forward to the winter hush as a time of respite from garden work. But it’s also a time to imagine possibilities and hatch plans.

On short, dreary days I like to walk through the garden to get a clearer view of its evolving structure. Without the distraction of vegetables, flowers, and foliage it’s easier to imagine what might come next.

Indoors, I turn to the collection of catalogs on the coffee table. “Do you need all of those?” Christopher asks, pointing to my growing library.

“Why yes, I do.”

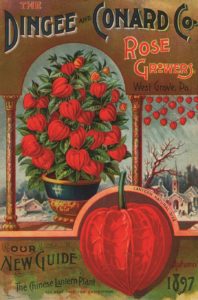

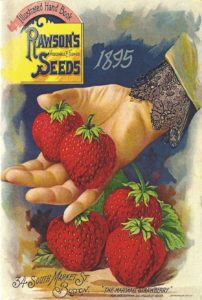

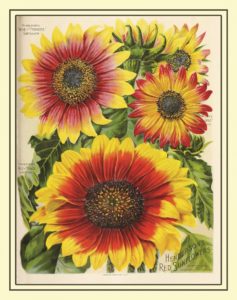

This annual pile of possibilities used to induce mild panic and impulsive seed ordering in me. But it no longer does. During the pandemic, I took the time to actually read the catalogs and realized that plant porn — those seductive photographs of green beans and lettuces that promise so much and lead to end-of-season seed surplus — was not all they had to offer.

Seed catalogs have since become my portal to a universe of websites, blogs, and podcasts full of gardening information that have made me realize what a beginner I am.

A Garden Plan

Someone at the Gardener’s Path website (gardenerspath.com) suggested I draw up a detailed, at-scale kitchen garden plan and that I create a calendar for succession plantings over the entire growing season. Armed with those, I resist ordering every pretty variety on display and instead try to predict more closely how many seeds I can actually use. Having a plan has made a real difference, not just in my seed-ordering habits but in my garden’s success.

The “Grower’s Library” on the Johnny’s Selected Seeds website (johnnyseeds.com) got me to calculate the specifics of my successive plantings — including the pivotal last frost date that told me when the cold season plants like lettuces, kale, leeks, radishes, and peas should go in. I plotted germination and harvest estimates to see which early seeds (like radishes) might grow fast enough to allow for two crops to grow before the next round of seeds (beets, carrots, and chard) were planted.

I learned that I should plant the three rows I had designated for lettuces a week apart to extend the harvest. And I no longer guess when to plant beans (they go in after the carrots and before the okra) or buy tomato starts (much later than I usually would). My fall plantings are not just an afterthought; they’re solidly part of the plan. My garden is more productive now.

Mission-Driven Seeds

As I read, I figured out that seed companies have different personalities and structures. I’m drawn to small, family, or employee-run companies. And I’m on the lookout for non-GMO (non-genetically modified), open-pollinated, and heirloom seeds. So, Christopher, I guess I don’t need every catalog after all.

Open-pollinated seeds are those that produce plants largely identical to their parents and are pollinated by the wind, bats, insects, and even rain. Seeds from open-pollinated plants may be harvested and planted in the next season. Heirlooms are open-pollinated seeds that have genetic lineages going back at least 50 years. They typically have unique flavors and other qualities not found in commercially grown varieties.

I’ve learned hybrids also have a place in the garden. These are seeds bred to resist certain diseases and pests or to produce specific characteristics — hello shorter carrots and faster-growing eggplants and less temperamental peppers. Because Truro is just not Tuscany.

Organic seeds appeal to me but seeds that are officially designated that way are costly. If you read your catalogs closely you will find some seed growers offer de facto organic seeds without the official government imprimatur.

Finally, as tempting as I find the exotic seeds in catalogs from the South (who doesn’t want to grow Moon and Stars Watermelons?) I mostly now stick to selecting from seed companies based in colder New England states.

Saving and Winnowing

Before I assemble my final list of purchases, I’ll make three money-saving moves. First, I’ll go down to the basement where I keep the tattered, folded-over packets of last year’s leftovers in a sealed glass jar. Since I’ve been planning more carefully, I don’t have nearly as many extras as I once did. But there are always a few, and they can be successfully stored in any cool, dark, dry place.

In my experience, onion, parsley, and spinach seeds are good for a second season. Bean, pea, and okra seeds work in year three. Same with carrots and turnips. I’ve grown peppers, chard, squash, cabbage, beets, tomatoes, eggplants, cucumbers, and lettuces from seeds bought four years ago. Just know that the older the seeds the lower the germination rate: plant extras.

I love the seed libraries at the Eastham and Truro public libraries. These give you access to seeds from local seed-saving gardeners, and often you’ll find they’re from varieties not available commercially. If you have a friend who gardens, consider a preseason exchange. My neighbor Stephen, whose garden off Depot Road puts mine to shame, often has more seeds than he can use.

A final winnowing of my selections is based on the fine print in the catalog descriptions. If there’s a pest or disease that’s been plaguing me, I know it’s time to test out a hybrid that is bred to be resistant. I also fact check myself: how much sun do my beds really get during the growing season? There’s no use growing tomatoes or cucumbers in the shade or spinach in boiling full sun where it’s sure to bolt.

Orders placed, sun still low at 4 p.m., I head to the sofa, straighten the catalogs on the coffee table. And, well, maybe one last peek won’t hurt.