EASTHAM — Wellfleet is world-famous for oysters. Neighboring Eastham is not. But there are folks in town who are trying to change that.

One is 31-year-old Jared Collins, whose family has been here for five generations. Jared has three small shellfish grants in Town Cove, including the first grant in the town of Eastham, dating to 1928. For his father and grandfather, oystering was a hobby, but Jared now makes a living from it. Collins Cove Oyster Farm has one employee, 300,000 to 400,000 oysters in the water, and plans to expand.

“Oysters are a global market, and they’re good for the environment,” said Collins, who was elected to the Eastham Board of Selectmen in May. “It’s a great business to be in. You get to be out on the water in the sun all day.”

Cape Cod growers produced 57 percent of the state’s total of farmed oysters in 2018, according to the Div. of Marine Fisheries (DMF). Wellfleet was the top producer on the Cape, with 10.74 million oysters, valued at $5.75 million. Barnstable was a close second, with 10.69 million. Eastham and Orleans (which are counted together by the DMF) came in fourth, behind Dennis, with 1.84 million oysters, valued at $1.04 million.

But the Eastham-Orleans aquaculture sector is growing fast. Between 2014 and 2018 the oyster harvest in those two towns increased by 300 percent. Wellfleet’s oyster production, already robust, increased by 73 percent over the same five-year period.

A waiting list for grants

There are now 26 aquaculture licenses in Eastham, with a waiting list of over 40 applicants, according to Eastham Shellfish Constable Nicole Paine. Five years ago, there were only 17 licenses and no waiting list, she said. A recent meeting of the newly formed Nauset Commercial Shell Fishermen’s Association, drawing from Eastham and Orleans, attracted over 20 people.

Growing oysters is no picnic. In summer, the bugs are pesky. Throughout the year, hazards require constant vigilance: predatory snails, sponges, red tide, ice, flooding. The floating “envelopes” of growing oysters must be regularly cleaned of muck and seaweed, and many growers have to drag heavy baskets of oysters in handcarts over wet sand flats for long distances.

For Scott Sebastian, the challenges outweighed the rewards, and he got out of the business last year after farming a grant off First Encounter Beach in Cape Cod Bay with his brother and a partner for a decade.

“One year all the seed died,” Sebastian said. “The hatchery replaced it, but we had no income that year. And it was hard to market Eastham oysters. They do not have the Wellfleet oyster legacy.”

In the summer season, when demand is high, the market for Eastham oysters was better, said Sebastian. But after Labor Day, it got much harder.

Middens of shells discarded by Native Americans are sure signs of the abundance of shellfish in this area before the arrival of Europeans 400 to 500 years ago. Billingsgate — an erstwhile island in Cape Cod Bay between Wellfleet and Eastham that now pokes above water only at low tide — was named by colonial-era settlers after London’s famed Billingsgate Fish Market. From around the time of the Civil War until World War II a company called Sealshipt Oysters dominated the oyster business in Wellfleet. As recently as 1947, Sealshipt employed 125 people in Wellfleet and 600 in Boston. But eventually oysters and other marine life were ravaged by overfishing, disease, habitat change, and other factors.

In The Famous Beds of Wellfleet: A Shellfishing History author D. B. Wright offers this excerpt from the town’s annual report for 1958: “The commercial shellfishing industry is a negligible factor except during scallop season.” In 1962 there was “no sign of any oyster spat on the flats of Wellfleet.” In the late 1960s, though, the town began to promote shellfishing again in an organized way, and now the annual Oyster Fest in October draws about 20,000 visitors, who consume hundreds of thousands of oysters in a single weekend.

Restoring the oyster to the Outer Cape

Fifty years ago there were virtually no oysters at all. Wellfleet and Eastham today have both farmed and “wild” oysters, but the oysters that are here now are all the product of human activity. The effort to restore oysters in Eastham is more recent, and it is succeeding.

Henry Lind retired 10 years ago after a long career as Eastham’s shellfish officer. “I was hired to figure out why Eastham’s efforts to bring oysters back to town had not resulted in natural populations in Nauset Marsh,” Lind wrote in an email from his sailboat, en route back to Cape Cod from Florida. “This was despite Wellfleet having plenty. We were funded in 1999 to construct an aquaculture training facility and hatchery, introducing and encouraging private aquaculture and municipal propagation. By the time I retired, a resident population of oysters had been re-established in Nauset Estuary.”

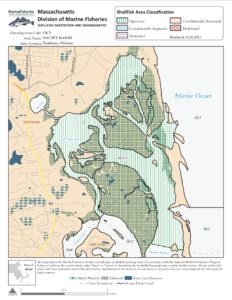

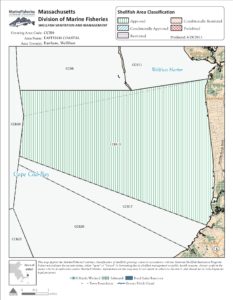

The estuary, one of the two main areas for shellfishing here, comprises Nauset Marsh, which is within the boundaries of the Cape Cod National Seashore; Town Cove, which is mainly in the town of Orleans; and a few linked saltwater kettle ponds. The other main shellfishing area in Eastham is the littoral zone in Cape Cod Bay, where the town reached an agreement with the Nature Conservancy in 2009 to allow shellfish grants.

Wellfleet Harbor is more enclosed and protected than the growing areas in Eastham, and that may have something to do with why oysters thrive better in Wellfleet. Oysters like to attach to the bottom, and the spat — or larvae — needs to stay in a confined area.

“You need a critical mass of spawning adults,” said Lind. In Eastham, “practically all the water in Nauset Estuary turns over twice a day” due to tidal flushing, he added. The bayside waters in Eastham are also more exposed to Cape Cod Bay.

Modern oyster farming depends on young oysters grown in hatcheries, known as upwellers. When the oysters are big enough, they are moved to the growers’ grants, where they are contained in floating baskets, called envelopes, to mature, a process that takes about three years. The “wild” oysters of today are basically strays from aquaculture.

A growing role for aquaculture

The re-establishment of shellfish has environmental benefits, mainly because they are filter feeders that remove nitrogen from seawater. Nitrogen runoff from fertilizers, septic systems, and highways is the main pollutant contaminating salt waterways in this area, and shellfish may be part of the solution.

In the big picture, global fishing stocks are severely depleted, so aquaculture will play an increasingly important role in the world food supply in the coming century. And shellfish are a big part of aquaculture production.

“Shellfish aquaculture is booming, and most of it is oysters,” said Sandy Macfarlane, a former shellfish biologist and conservation administrator for the town of Orleans who is now an industry consultant. “Demand is high, and the supply chain is growing. Oysters are a big, big deal.” Oysters are now being cultivated all up the East Coast of the U.S., she said.

According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, from 1984 to 2013 world shellfish production increased nearly fourfold, from 3.8 million tons to 14.1 million tons, and the proportion of that total originating from aquaculture shot up from 50.6 percent to 90.2 percent.

Fisheries of the United States 2017, a publication of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, estimated that oysters have eclipsed salmon as an aquaculture crop in the U.S. (36.6 million pounds vs. 35.7 million pounds).

Demand for oysters continues to grow, and Eastham growers are bullish on bivalves. Al Cestaro is another oysterman who, like Collins, is an Eastham selectman. A U.S. Army veteran, Cestaro has worked a one-acre oyster grant in Cape Cod Bay with his brother for the past three years.

“When you get oysters from Eastham, you know you’re getting something good,” Cestaro said. What makes them so good, he said, is “all the things that make our lives as fishermen miserable: all the health inspections and quality inspections.”

Scott Sebastian, who gave up his grant last year, wishes that he could have stayed in, and said, in addition to the difficulty of marketing Eastham oysters, the problem was too little support from the town. Sebastian was a member of the town’s shellfish and waterways advisory committee, whose charge, in part, was “to work to preserve and enhance shellfish populations and habitat resources in order to maintain and improve a sustainable fishery and aquaculture industry.”

But the advisory committee was dissolved by the board of selectmen on March 6, 2019 and replaced by a working group that reports to the town’s conservation department. The reorganization was proposed by Selectman Cestaro, but Sebastian said the committee members were not told it was being disbanded. Select Board Chair Aimee Eckman told the Independent the advisory committee had a limited mandate to revise regulations and that it had fulfilled that mandate. At the March 6 selectmen’s meeting, several town officials said the shellfish advisory committee’s discussions had been problematic and that they hoped a restructuring would smooth its functioning.

Editor’s note: Due to a fact-checking error, an earlier version of this article misstated the number of members of the Wellfleet Shellfishermen’s Association. There are now more than 100 members, according to Ginny Parker, the group’s director.

Also, due to an editing error, a statement by Scott Sebastian about Eastham oysters being marketed as Wellfleets was reported inaccurately. He was referring to restaurants, not growers, he now says. “Restaurants do market their oysters as Wellfleet oysters,” Sebastian wrote, “because of the size of the market for the name. ‘Wellfleet oysters’ is the most recognized brand, and that is what tourists expect. It is very difficult and dangerous for a grower to mislabel their oysters.The grower must label, log, and tag all bags sold to a distributor. He or she also logs this information with the state. Both the distributor and restaurant keep records of the origin of these oysters in case of illness. If one was to get sick, the tags are referenced and go back to the grower so that the town or state can investigate whether disease is present in the water, or if the oysters were mishandled during harvest, transportation, etc. In my nine years of oyster fishing I have not witnessed any illegal activity of this nature from any grower that I was in contact with.”