TRURO — Ada Worthington, whom everyone called Tiny, created a national fashion trend during the Great Depression from the beauty she saw in a piece of fishing net she picked up on Cold Storage Beach in North Truro.

“She was not like anyone else,” says her daughter, Diana Worthington, who lives down the street from where Tiny started Cape Cod Fish Net Industries in 1933.

Tiny, who, according to Seth Rolbein, in a story posted in 2019 on the Cape Cod Fishermen’s Alliance website, stood “six feet tall in her size 10 army boots,” was born in Buenos Aires in 1899.

The overview of Ada and her husband John’s family’s papers (1897-1988) at Harvard’s Schlesinger Library says she was educated in England and worked in the ambulance corps there during World War I. But in New York, she dabbled in theater alongside a career in nursing.

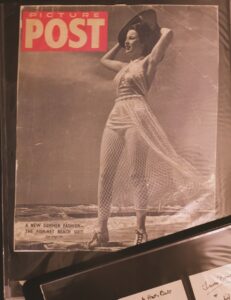

A certain confidence about entertaining an audience and putting on a show served her well when she decided to take her fishnet fashions to the Big Apple to make cold calls on some of the biggest department stores there. She soon had her products in Lord & Taylor, Bergdorf Goodman, and John Fredericks. By the late 1930s, Tiny’s fishnet fashions — from dresses to dolls and everything imaginable, it seems, except stockings — defined a hot trend.

Later, when the fashion world moved on, Tiny invented new possibilities for fishing nets, spinning them into practical items as diverse as curtains, shopping bags, slipcovers, and even industrial fan covers. But none of this would have been possible without a robust fishing industry off Cold Storage Beach in the early 20th century.

At the time, trap boat fishing was popular in the shallow inshore waters along the bayside beaches of the Outer Cape. Also known as weir fishing, this method utilized large cotton nets that were spread between hickory poles sticking up in the water. Schools of fish were led through a series of nets toward a central bowl where they were trapped and then captured by fishermen approaching by boat.

“Every year, fishermen tarred their nets on the beach,” says Diana. The nets were passed through hot coal-tar, which coated the fibers to protect and stiffen the nets. One day Tiny was on the beach when the fishermen were tarring, and she grabbed a piece of net and took it home. Her first fishnet creation, says Diana, was a curtain valance.

Tiny had other ideas for the nets but would have to ask fishermen what they thought first. “She didn’t want to be messing around with their nets if they didn’t like it,” Diana says. She invited a few of the fishermen to her home to see her curtains, which they deemed just fine.

Tiny turned her project into a cottage industry. She started out working from a ramshackle loft by the beach and would haul her nets down to the water’s edge and dye them in copper vats over a fire, according to Diana’s daughter, Dawn White. Eventually, she moved her operation to a place at the end of Pond Road, a former schoolhouse that is now Robert Cardinal’s studio.

“As her designs took shape, her clothing and accessories were pieced and sewn together by as many as a dozen wives of local fishermen in North Truro,” says White. Her burgeoning success was important to many during the lean years of the Depression.

Advertisements from the era feature the Bracelet Basket Bag (“Gay and smart for town or country sportswear”), the Eisenhower Jacket (“A glamorous separate for daytime or evening wear that will last a lifetime. Ideal for travel”) and the Turtle Necked Shirt (“In fine minnow net”). Often, Tiny’s products had multiple uses. Bag o’ Tricks was a favorite: a reusable bag that could also serve as a belt or scarf. Frugality and resourcefulness were central to these Depression-era products.

By the late 1930s, Tiny had fully hit her stride. The fashion press loved her products and her story. “Fishnet is so busy catching the girls’ fancy that mere fish may get the go-by any day now. It’s a fashion and the rage,” wrote Ruth Carson in Collier’s. Celebrities got ensnared in the trend, too. The Duchess of Kent, Bea Lillie, and Bette Davis all wore Tiny’s designs.

By the 1950s, the designs had been copied and fashion had moved on. Yet Tiny maintained her shop in Truro, creating new designs until she closed it in 1970. By that time, too, weir fishing was in steep decline on Cape Cod and sourcing cotton nets had become challenging.

Tiny had arrived in Truro with a husband, John Worthington, who had his own adventurous career. He had enlisted in the Marines during World War I, worked in oilfields in Mexico, learned to fly and competed in air races, and was a salesman for the Merrimac Chemical Company. Diana says that her father played an important behind-the-scenes role in Tiny’s success.

John had grown up in Dedham but visited Truro every year. He was fascinated by weir fishing, joining men on their trap boats for summer work from a young age. “He’d walk down the train tracks and go out to the traps in the bay with the men at four in the morning,” says Diana.

John and Tiny were married in 1926, and in 1932 they bought a house on Depot Road just before the full effects of the Great Depression were beginning to be felt locally, Diana says.

By then, fishermen didn’t have money to buy nets for their traps, Diana says. Motivated to help the men he had met years before on the trap boats, John helped revive North Truro’s cold storage operation, which had gone belly up.

At his Pond Village Cold Storage Corp., Worthington used knowledge gleaned from working on oil rigs to develop a system whereby a pulley and rails could haul fish from boats directly to the shore. He built a three-story building where the fish were frozen and stored before being loaded onto trains that ran on tracks alongside the beach.

Eventually, fish nets filled the beach again, and that’s when they caught the imagination of John’s enterprising wife. “He opened the door for Tiny,” says Diana.

Tiny bolted through it. “She saw the beauty of the net and its usefulness beyond fishing,” says White. “Her ability to imagine the usefulness for this one material was almost infinite.”