Twenty years after the Revolutionary War had crippled Cape Cod’s economy, as prosperity was slowly returning, another hardship befell its residents.

The U.S. was neutral in the Napoleonic Wars, but American shipping was targeted, ensnaring the young nation in the ages-old struggle between England and France. In 1807, Congress passed the Embargo Act, prohibiting trade to all foreign nations. Though embargoes were eventually lifted on American shipping except for cargoes bound for Great Britain and France, tensions with Great Britain had been inflamed. And when a formal declaration of war with Great Britain was made in June 1812, the Royal Navy promptly established a blockade along the Atlantic coast.

The Cape, with its exposed position, was at the mercy of the enemy. British warships, making use of the capacious harbor at Provincetown as their rendezvous, dispatched smaller barges to harbors and creeks to harass Cape Cod fishermen, keeping them under strict surveillance and depriving them of their livelihoods. But for a courageous few who risked life and property to run the blockade — these runners were usually merchant vessels that used stealth and speed to fetch and deliver essential cargo or mail — communication with Boston and even with other Cape Cod towns was all but cut off.

In 1912, on the hundredth anniversary of the war, a slim volume, 1812: A Tale of Cape Cod, was published by Charles W. Swift of Yarmouth Port. The book, by Michael Fitzgerald, was historical fiction described as a “stirring tale of Cape Cod during the War of 1812,” to be welcomed by “every American whose patriotic pride is stirred by the recital of heroic deeds performed by the men who so valiantly struggled against fearful odds in the days when the nation was young and comparatively weak.”

Fitzgerald, a native of Ireland, had arrived in the U.S. in 1897, settled on Cape Cod, and worked for many years for the French Cable Company. He was, no doubt, inspired to pen his tale after reading accounts of the events of the war in histories by the Rev. Enoch Pratt (1844) and Frederick Freeman (1869). Pratt, who served as minister of the Eastham Congregational Church for several years beginning in 1842, no doubt had heard stories of 1812 and had known many who endured the war’s privations.

Fitzgerald’s tale features two real-life master mariners, Matthew “Hoppy” Mayo, who was 35 when the war began, and Winslow Lewis Knowles, who was 26. It has a supporting ensemble of distinguished Eastham citizens, among them the Rev. Philander Shaw, Obed Knowles, Timothy Cole, Harding Knowles, Samuel Freeman, and Heman Smith, as well as blacksmith and poet Peter Walker and innkeeper Thomas Crosby. Many of these now rest in marked graves in Eastham’s cemeteries, and one can imagine them gathered at Crosby’s Tavern on Bridge Road, then the heart of the community, discussing their plight.

Despite the threat of capture, in September 1814 Captains Mayo and Knowles set sail for Boston from Eastham in a whaleboat laden with rye, an important local export. Having skillfully evaded the enemy, the mariners arrived safely, sold their crop, purchased necessities for the community, and began their sail back to Eastham in a larger borrowed vessel. Seeing a schooner at anchor and believing it to be a fishing boat — and thinking little more of it — the seasoned sailors fell victim to a trap.

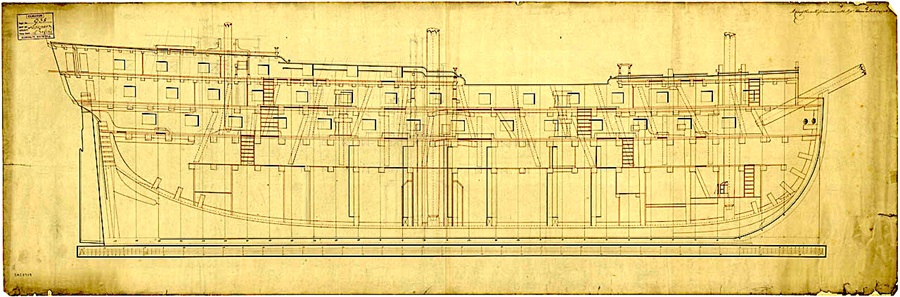

Taken captive, they were conveyed to the HMS Spencer, a full-rigged 74-gun 180-foot frigate commanded by Capt. Richard Raggett. Known by locals here as the “Terror of the Bay,” the Spencer patrolled the coast, seizing Cape Cod vessels and crews and terrorizing towns with threats to bombard vital saltworks if ransom was not paid.

On board the Spencer, Mayo and Knowles offered to ransom themselves for $300 to save their vessel and goods. While Capt. Knowles returned to Boston to raise the ransom money, Capt. Mayo was placed on a schooner with 23 crew to serve as their pilot for a survey of the coast and its dangerous shoals. Caught in a storm, Mayo devised a scheme to run the schooner onto the shoals. Deliberately anchoring in ground that would not hold, the schooner broke free. Mayo advised that they “run for it,” making for an inlet only to find themselves in an ebbing tide and soon high and dry on the Eastham flats. “Hoppy” Mayo had outwitted his captors.

Townspeople who had assembled at the beach marched the crew to Crosby’s Tavern where, it was said, they were “hospitably entertained.”

When Capt. Mayo gave a full accounting of his adventure, the town fathers praised his gallantry, but the story also raised concerns that Capt. Raggett would likely demand punishment for the Royal Navy’s humiliation. The townspeople released the prisoners, in hopes that would placate the commander.

Instead, from the Spencer there arrived a demand for $1,200 to secure the safety of homes and saltworks. The ransom was paid — Brewster had also paid a ransom, though Orleans and Barnstable had refused — and the townspeople of Eastham, whose nerves had been rattled by fear and intimidation, were reassured of their protection for the remainder of the war. Eastham returned to peaceful times, only to be visited a few months later by another enemy, typhus, that claimed more than 70 residents in 1816.

As for Capt. Winslow Lewis Knowles and Capt. Matthew “Hoppy” Mayo, the historic record is silent on the outcome of Knowles’s trip to Boston to secure ransom money, but Pratt writes that he later engaged in business with considerable success. The commemorative program prepared for Eastham’s tercentenary in 1951 notes that he made several trips around the Horn to the Pacific, sailing to San Francisco with cargo for the burgeoning gold rush town. By 1850 he had moved to Brewster, where he died in 1870.

“Hoppy” Mayo, along with several other Eastham mariners, engaged in privateering during the war. That is, they were commissioned by the government to carry out maritime warfare using their own private vessels, a dangerous but profitable enterprise for sea captains. According to Pratt, he captured a number of prizes over a five-month period.

Capt. Mayo was remembered in the town’s tercentenary program as having perished with his crew, without a trace, on a coastal voyage from Norfolk, Va. in 1832.