Towns have myriad ways of honoring their war dead. Grand monuments, parks, and plazas are built for contemplation and reflection. Street corners named in a soldier’s honor are adorned with wreaths and flags. In Provincetown, one reminder of the toll war takes stands in the distance, at Long Point, near the lighthouse.

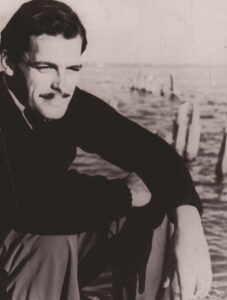

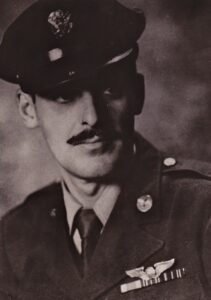

It honors a fallen soldier the town has never forgotten, Charles Darby, an artist with matinee-idol looks and a soft Southern accent. Raised in Maryland, Darby washed ashore at Provincetown in the early 1930s. Invigorated by the town’s élan, Darby studied with E. Ambrose Webster, whose avant-garde style seemed to suit his whimsical and leisurely approach to life. He exhibited at the Provincetown Art Association and became a beloved member of the fraternity known as the Beachcombers, who still gather in an old fishermen’s shed at the foot of Bangs Street.

Charles Darby surely would have grown old in Provincetown, but in 1942 the Army Air Force called him away from his Eden. He was assigned as a radio operator with the 77th Squadron, 435th Troop Carrier Group and took his basic training in Sioux Falls, S.Dak., a world away from Provincetown. And yet, to his delight, one day he spotted a print of a painting by his friend and fellow Beachcomber John Whorf.

In a letter to the Provincetown Advocate in October 1942, Darby described walking into the USO there “and darned if there wasn’t a picture by John Whorf hanging on the wall,” he wrote. “Made me sort of homesick for a minute. I went out and found some sand and poured it into my shoes and hung around a fish store for a while until I felt better.

“Anyway,” he continued, “appreciation for Provincetown harbor increases in the square of how far you get away from it and you can’t get much farther away from water than South Dakota. A subscription to the Provincetown Advocate is worth the price if only to look at the picture on the front,” he wrote, referring to the panoramic engraving of the town on its flag. “I enclose two bucks,” he concluded.

In November 1943, Darby was sent to England. He participated in the Normandy invasion in June 1944 and airlifted supplies to the advancing Allied armies. On Sept. 19, 1944, his plane, towing a glider, was shot down over Holland. The glider was successfully released, after which the crew bailed out safely. Darby and another crew member rendezvoused with other glider pilots from the squadron and caught a flight back to England.

Just days before that mission, Darby had written the Beachcombers that he had been working most of the time, thinking about Provincetown. “You don’t know what I’d give to be back there sometimes, fall afternoon, chili cooking on the stove, and a fine new bottle of whiskey standing by, perhaps a pale ray of late light shining through it,” he wrote.

A month later, on Oct. 17, returning from a mission to the continent and with visibility poor, Darby’s plane crashed into a hillside at Fulking, Sussex. All four crew members were killed instantly. Investigators determined that if the plane had been flying just 150 feet higher it would have cleared the crest of the hill.

Darby’s bereaved father poured out his “sorrying over the dear fellow” in poignant letters to the Beachcombers, telling of his son’s affection for Provincetown, a place that had the greatest fascination for him: “He loved the quaintness of the place, the bright sunlight and ocean and most of all the sand downs with the wild sand roses of which he talked to me incessantly, but it was the friends of which he never tired of telling me about.” Mr. Darby asked if a plaque might be fastened to a stone and set overlooking the ocean in the lonesome sand dunes, a memorial to an unsung soldier. “I only thought it would in some small way tie more closely Charles to his beloved Provincetown,” his father wrote.

Recorded in the minutes of the Beachcombers’ Nov. 18, 1944 meeting is the suggestion that a spot be selected upon which to erect a monument “to an unsung soldier who loved the dunes.” At the next meeting it was moved that a cross be made for Darby.

At six bells, on a clear afternoon in October 1946, a cross built of old railroad ties, with a bronze plaque fashioned by sculptor Bill Boogar, was dedicated by the Beachcombers on the lawn of the Provincetown Art Association. Sometime in the late 1950s or early 1960s the cross was removed to Long Point and set next to the lighthouse into a sand hill, liberal with roses, fulfilling Mr. Darby’s wish for his son.

The cross, silhouetted against the sky, has weathered gales, blistering heat, and numbing cold. It beckons visitors to Long Point to amble up the dune to have a look, most assuming it to be a memorial to those in peril on the sea. An enamel plaque, replacing the original bronze, tells the story: Charles Darby, Gallant Soldier, Killed in Action, October 17, 1944.

On Nov. 9, 1944, the Advocate printed a moving tribute to Darby, who is buried in England’s Cambridge American Cemetery. The paper’s managing editor and publisher, Paul Lambert, a gifted writer, expressed the sorrow and resolve of the community when he wrote: “We who remain will never be able to extend ourselves in the directions to accomplish the things which those young men the war is taking would have done. Their gifts and their promise have gone from this and coming generations. But we know — or should know by this time — that our determination to put a final stop to this ravage of the human race can no longer be the empty words of patriotic speeches. It must be done. It must be done.”