As the Great Depression spread its pall, President Franklin Roosevelt implemented the New Deal, a series of programs aimed at restoring American prosperity. Among the initiatives were Works Progress Administration (WPA) projects intended to lift artists out of poverty. The WPA Federal Writers’ Project, established in 1935, put nearly 10,000 writers, editors, and researchers to work. Its most important achievement was the American Guide Series — detailed state histories offering cultural insights, suggestions for automobile tours, and a portfolio of photographs all intended to project a positive image of the country.

On Cape Cod, Josef Berger (1903-1971), writing under the pen name Jeremiah Digges, was one of the guide’s authors. He lived in Provincetown while he gathered folklore, legends, anecdotes, and beguiling reminiscences of the early days of Cape Cod for his Cape Cod Pilot, a Loquacious Guide, published in 1937.

Visiting all the towns on the Cape, Digges saved a special compliment for Eastham: “If I were a judge of a beauty contest and the fifteen towns of Cape Cod were marched before my eyes, I think I should give the prize to Eastham. Her hard old features are not regular; her complexion is lumped and full of scars from her everlasting duel with the sea, and there is no ‘pose’ in her smile, which comes grim and sparing through the wrinkles of centuries. But you will not have to look long to find ‘character’ in this old townface….”

Seven families migrating out from Plymouth in 1644 were the first Europeans to settle in Eastham. Among them was Thomas Prence, also spelled “Prince” (1600-1673), who was granted a special dispensation during his second term as Plymouth Colony governor to live outside of Plymouth.

On his farm near Fort Hill, a portion of which was owned generations later by the Doanes, another of Eastham’s founding families, Prence built a home that stood long enough to be photographed in the late 19th century. After it was razed, its door stone was saved and installed, in 1910, as a threshold at the Pilgrim Monument.

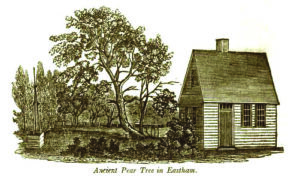

Prence also planted a pear tree brought from England. In December 1848, two hundred years after it was planted, newspapers were “sorry to be obliged to record the destruction of that venerable relic,” the tree having blown down during a gale.

By then it had become a famous old tree. A decade earlier, the Yarmouth Register reported that it was in a “sound and perfectly healthy state.” The fruit was excellent, though small. In 1839, historian John Warner Barber published an engraving of the ancient pear tree in his Massachusetts Historical Collections, noting that the tree was still in a vigorous state. In 1840, the Prence pear was mentioned in company with the famous pear tree planted by John Endicott in Danvers. In 1842, the Register again mentioned the Prence tree, saying that “it has constantly borne a large crop of excellent pears.”

Then came its apparent demise, an event that Thoreau referenced in describing an 1849 visit in his Cape Cod. But, oddly, that was followed by still more stories about the old tree — stories in which it seemed to still bear fruit.

In 1853, a travel correspondent remarked on the “venerable pear tree which, in point of age, is not unworthy to rank with the Endicott pear tree in Essex county.” He added that the Eastham tree was “not less than two centuries in age.” In July 1870, another correspondent passing through Eastham wrote that “Gov. Prince’s pear tree is pointed out as a relic of those ancient days.” In June 1877, it was reported that fall pears from a tree planted by Gov. Prence were exhibited at the Massachusetts Horticultural Society by Ezekiel Doane of Eastham.

According to a family genealogy, Capt. Doane, born in 1813, lived an adventurous life, going to sea on a fishing boat at 11, after which he worked in the coastal trade and delivered ammunition to American forces during the Mexican War. After the war, he returned to Eastham and purchased the Prence farm, though his landlubber days were short-lived. He sold the farm and returned to sea, heading west for gold in ’49. Two years later, he was back in Eastham. He repurchased the Prence farm and lived there until his death in 1890.

An item in the Hyannis Patriot in 1894 may hold a clue — in the use of the word “scion” — about the puzzling reappearance of the old pear tree. Could it be that the tree from which Ezekiel Doane harvested his fall pears was not the original Gov. Prence tree but, instead, a cutting?

Here is the passage in question: “One of the old landmarks of the town has lately been removed, the old pear tree — a scion from the renowned Gov. Prence pear tree that has stood for so many years on the Doane farm, by the roadside.” For more than 40 years, continued the story, the tree (presumably the tree that had been “destroyed” in 1848) had “gradually slanted to the eastward, but still seemed firmly rooted and bore fruit.” The story added that there was “one more old pear tree of the same kind standing on what used to be the Gov. Prence farm.”

When Jeremiah Digges visited Eastham in the 1930s, he found a flourishing pear tree, “a descendant of English stock and the work once removed of the Governor’s hand,” still on the Prence farm, then owned by Abelino Doane (1857-1941), the son of Ezekiel Doane.

In the post-war years, when happy days had returned, how many travelers, clutching their Cape Cod Pilot, hit the road hoping for a glimpse of the old pear tree? And might there still be, today, an offspring of the Prence tree rooted somewhere in Eastham?