When Philip Smith Rich died in Provincetown in 1879, he took details of surviving a harrowing shipwreck to his grave. Writer Herman Jennings, in his classic Provincetown Or, Odds and Ends from the Tip End (1890), supposed that the last survivor of the Ardent disaster would tell his story in full, but it was not to be. “Mr. Rich passed away without relating it.”

But so extraordinary in the annals of marine disasters was the catastrophe of the whaling brig Ardent, that much of the story is known to us today from newspapers that reported details of the calamity.

The son of David and Abigail Rich, Philip was 18 years old when became one of 14 crew members, most hailing from Provincetown, who sailed from Boston to the Western Islands — as the Azores were then known — on March 19, 1823.

Bound home on Sept. 13, with an anticipated arrival date in mid-November and laden with sperm oil after a successful voyage, the Ardent was three hundred miles southeast of Nova Scotia when it sailed into a raging tempest on Sept. 28. A violent gust knocked the vessel on its beam end, separating it from its whaleboats and washing three crew members overboard to their “silent sleep.”

One of the three lost was Jonah Gross, whose father, Alexander Gross, had had his own harrowing experiences as a prisoner during the Revolutionary War. The eleven surviving crewmembers clung to the quarterdeck, the only area of the foundering vessel that was not underwater.

Using a sail as an awning, crewmembers sheltered from the weather and secured several barrels of food — beef, pork, bread, and molasses had washed out of the hold, though the bread and molasses were spoiled by salt water and oil. Meager rations as well as several quarts of rainwater collected in the sail provided temporary sustenance.

The Ardent displayed a distress flag, according to contemporary reports, but the wreck went undiscovered by at least three passing vessels. By early October, the ship’s delirious crewmembers had begun to succumb to starvation, dehydration, and exposure, falling away into the black abyss. Two perished on Oct. 6, and another three days later. One died on Oct. 13, and two more on Oct. 17, the day after all their food had run out.

Eight days later, on Oct. 24, nearly one month after encountering the gale and with the weather having finally moderated, the Ardent was spotted by the British packet Lord Sidmouth, then on a voyage from New York to Falmouth, England. The ship was one of Britain’s famous “Falmouth packets,” privately owned vessels contracted by the post office to carry mail to the far corners of the British Empire.

Lloyd’s List, which provided weekly shipping news beginning as early as 1734, records that the Lord Sidmouth sailed from New York on Oct. 4, departing Halifax on Oct. 20 en route to Falmouth, England.

Upon discovering the Ardent, Commander Charles Pipon dispatched a boat to the waterlogged wreck and hoisted off the five debilitated survivors — Captain Samuel Soper; his cousin, mate Hix (sometimes “Hicks”) Smalley; and seamen Thomas Hudson, Cyrenius Small (sometimes “Smalley”), and Philip S. Rich. Though provided with treatment by the ship’s surgeon, Mr. Gibson, and furnished with clothes and all necessities, the suffering and exhaustion proved too much for Hix Smalley, who died onboard the Lord Sidmouth several days after the rescue.

There is no local documentation of the details of these mariners’ excruciating month on their wreck — it all happened early enough in Provincetown’s timeline that there was no Barnstable Patriot nor Provincetown Advocate to report them.

On Nov. 18, the Lord Sidmouth arrived in Falmouth and for the next month the survivors remained in England where they received treatment, rest, and a purse of money for their needs. Captain Samuel Soper later publicly thanked everyone who had cared for the desperate mariners.

After a 53-day voyage from Liverpool aboard the packet ship Lucilla, Captain Soper returned to Boston in mid-February 1824, having missed the November birth of his son, Samuel Thomas Soper.

(In 1853, as captain of the whaling schooner S.R. Soper, the younger Samuel would experience his own dramatic survival story. And in 1861, another son, Capt. Robert C. Soper, was cruising the waters off the mouth of the Mississippi River when the Confederate privateer Calhoun seized his vessel, Mermaid, and its cargo of oil. Taken prisoner to New Orleans, Soper and his crew eventually traveled by rail back to Massachusetts.)

Two of the other three surviving Ardent crewmembers, Thomas Hudson and Philip Rich, sailed for New York aboard the Manhattan on Dec. 17. Cyrenius Small remained longer in England for treatment of his wounds.

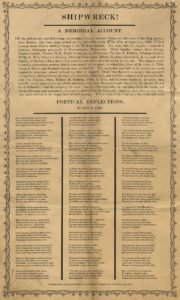

The sorrowful story of the Ardent inspired New Hampshire-born Seth T. Hurd (1800-1875) to pen a memorial account. Hurd, a traveling lecturer on English grammar, published the 1847 self-improvement manual, A Grammatical Corrector. He also founded the Brownsville Clipper, a weekly Pennsylvania newspaper that continued to publish until 1907.

Hurd’s “Shipwreck!” was printed as a broadside, likely in 1873 on the 50th anniversary of the wreck. A copy is among the Massachusetts State Library’s Special Collections. It recounts the story of the wreck and rescue, after which Hurd’s poem begins:

Some angel guide me while I write

The sorrows of that dismal night;

Where tempests rage, where billows roar,

And surges lash the distant shore.

Behold my friends! With pensive view,

The scene of Soper and his crew;

With candor view, with sorrow see

The truth of this catastrophe.