“These are the Highlands of Cape Cod, the most dangerous point on the Cape,” wrote Shebnah Rich in his landmark Truro history. “No place, perhaps, has witnessed more shipwrecks, and nowhere does a northeast gale agonize with more terrific fury than against these clay cliffs.”

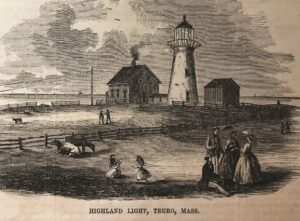

That is why, in 1797, less than 10 years after the U.S. Lighthouse Establishment was created, the first lighthouse on Cape Cod — the Highland Light — was built on the uplands the Nausets had named Tashmuit, “a place of springs.”

The land, including a grist mill, was owned by Isaac Small (1754-1816), one of Truro’s earliest proprietors. He received $100 from the federal government for 10 acres and another $10 for an easement across his adjoining property. Though the lighthouse site was not the highest elevation in Truro, it was said the sale was negotiated with the aim of appointing Small the light’s first keeper. The job was his until 1812.

Upon Small’s death, his land was divided between his sons. His second son, James Small (1787-1874), continued to farm and operate the grist mill.

In the 1830s, Edward Hitchcock, a professor of natural history at Amherst College and later its president, visited the Cape while preparing a geology of Massachusetts, published in 1841. “The most striking example which I have met with,” he wrote, “showing how productive the most barren soil may become, was pointed out to me by James Small Esq. of Truro on Cape Cod. In passing down the Cape, long before one reaches his farm, most of the country appears excessively and hopelessly barren. His farm, however, is based upon blue clay, and forms a fruitful oasis amid the sandy waste.”

By 1835, Small had built a farmhouse near the lighthouse and, in 1843, following in his father’s footsteps, he was appointed keeper of the light. For the next 16 years, except for the years from 1850 to 1853, James served either as head keeper or first assistant.

With his first wife, Patty Dyer (1786-1834), James had six children. He then married Jerusha Dyer (1804-1867), the widow of Atkins Hughes, with whom she had three children before Hughes was lost at sea in 1828. Two sons were born to James and Jerusha: Morton, who died in infancy, and Isaac Morton “Mort” Small, born in 1845.

Squire James Small, his obituary noted, was “justly esteemed as a man of marked intelligence and ability.” He served in the Mass. Legislature and on a commission for the protection and preservation of Cape Cod. His residence was one “where strangers and friends were heartily welcomed.”

Among those he welcomed was Henry David Thoreau, who lodged with James Small in his “solitary little ocean house” at Highland Light during at least three of the visits between 1849 and 1857. Entertained by Small and fascinated by the environs, Thoreau dedicated a chapter of his Cape Cod to his Highland visits.

As he and Keeper Small ascended a winding open iron stairway to “light up,” it was not lost on Thoreau that at that moment “many a sailor on the deep witnessed the lighting of the Highland Light.” Later, as he was drifting off to sleep, Thoreau contemplated “how many sleepless eyes from far out on the Ocean stream — mariners of all nations spinning their yarns through the various watches of the night — were directed toward my couch.”

Thoreau was prescient in recognizing “that the time must come when this coast will be a place of resort for those New-Englanders who really wish to visit the sea-side.” One wonders if he shared his intuition with James Small, for as tourists began trickling down Cape to Truro, Small made his Highland Farm available for lodging.

After James’s death in 1874, Mort added rooms to the Highland Farm, the first phase of an ambitious expansion that promised summer guests “pure air,” “excellent table,” “good surf bathing,” and “one of the finest views in New England.”

Sojourners came to the Highland bluffs for health, rest, and the “magnificent marine panorama” from the “edge of an eminence,” as writer Edward Augustus Kendall referred to the Highlands in his 1809 travelogue.

Isaac Morton Small made another use of his promontory view. From dawn to dusk, manning the marine telegraph station, Mort trained his brass telescope on the horizon, tracking the passage of ships, watching with a keen eye for any in peril, and forwarding his reports to the Merchant’s Exchange in Boston. It was a role he held for 70 years until his death at 88.

While his second wife, Lillian, known as “Aunt Lil,” tended to the comfort of guests lodging in the cottages and at the new Highland House Hotel built in 1907, Mort regaled them with tales of rescues and wrecks and memories of Henry David Thoreau.

Later, Small gave an interview in which he reminisced about Thoreau’s visits. Small, then a lad of 10, had walked the beach with Thoreau, marveling at all he knew about the ocean. There wasn’t anything, remembered Small, that Thoreau didn’t seem interested in, and when Mort’s father, James, asked Thoreau why he asked so many questions, Thoreau replied that he intended, someday, to write a book about Cape Cod.