Until summer returns, the art galleries in Provincetown are mostly quiet, though surely planning for next season’s traditional Friday evening strolls. That’s when everyone takes to the streets, zigging and zagging from gallery to gallery to experience the creative expression of established and emerging artists. And did we mention the wine and cheese at every stop?

The depths of winter need not, however, be a season of creative starvation. The Provincetown Art Association and Museum and the Fine Arts Work Center are open year-round, as is Provincetown Town Hall, on whose walls hang masterpieces from the early art colony, the sight of which may take some of the sting out of paying one’s property tax bill.

For those in search of a different kind of stroll, Provincetown’s historic cemeteries are a kind of en plein air art gallery. One could argue that all cemetery “art,” from stark colonial iconography to sumptuous Victorian design, is worthy of appreciation as an expression of human skill and imagination. But in our graveyards one finds personalized tributes to the disparate folk who shaped Provincetown and chose it as their final resting place.

Along Alden Street, bisecting the Catholic and Alden cemeteries, the first access road on the left as one travels from Shank Painter Road brings art lovers to the grave of caricaturist Henry Major, whose stone is adorned with a William Boogar bronze. Boogar, a celebrated sculptor and beloved member of the early art colony whose work can be seen at the head of MacMillan Wharf and in Truro’s Snow Cemetery, used one of his stylized, signature seagull sculptures for the bronze, adding wave and scallop shell flourishes. It is inscribed, “He has taught all men a respect for life.”

Born in Hungary, Henry Major arrived in America in 1923 and became well known for his caricatures of entertainers. He created a popular stock character, the Gay (in the dated sense) Philosopher, whose image, said to have been a self-portrait, was used on promotional items like matchbooks, calendars, and playing cards. The Gay Philosopher dispensed nuggets such as “Empty carts always rattle the loudest,” “Middle age is when our tripping becomes less light and more fantastic,” and “You can’t be a howling success simply by howling.” Said to have been soft-spoken with a twinkle in his eye, Major arrived in Provincetown sometime in the early 1930s and, though he was a married man, had a long-term relationship with psychoanalyst Clara Thompson, at whose home he died in September 1948 and in whose cemetery plot he is buried.

Like Truro’s Snow Cemetery, Provincetown has its own “artists’ corner” in the Alden Cemetery (Section A), where luminaries including Norman Mailer, Stanley Kunitz, Ross Moffett, Jack Tworkov, and Robert Motherwell repose side by side.

Motherwell maintained a summer home and studio in Provincetown beginning in the mid-1950s. He was the youngest of a group of New York Abstract Expressionists that included Jackson Pollock, Mark Rothko, and Jack Tworkov, though unlike his colleagues he also explored collage and printmaking. Motherwell’s memorable series Beside the Sea (1962) was inspired by Provincetown’s seductive light and pounding sea spray. His grave, marked by a large stone, bears a bronze inscribed with his signature.

Cross the invisible boundary into the Alden Old Section and find the marble sculpture on the grave of Nanno de Groot, one of the most distinctive works of art in the cemetery. Born in the Netherlands in 1913, de Groot spent years in the maritime and shipping business before dedicating himself to art. Self-taught, he moved to New York after World War II and was affiliated with Abstract Expressionism. Married in 1948 to poet and painter Elise Asher, de Groot arrived in Provincetown in 1956. By 1958, he and Asher had divorced (she later married Stanley Kunitz), whereupon he married artist Pat (Richardson) de Groot. He died just five years later. Pat designed and sculpted his headstone, a Zen-like dancing figure with arms encircled overhead. When she died in 2018, she was buried beside him.

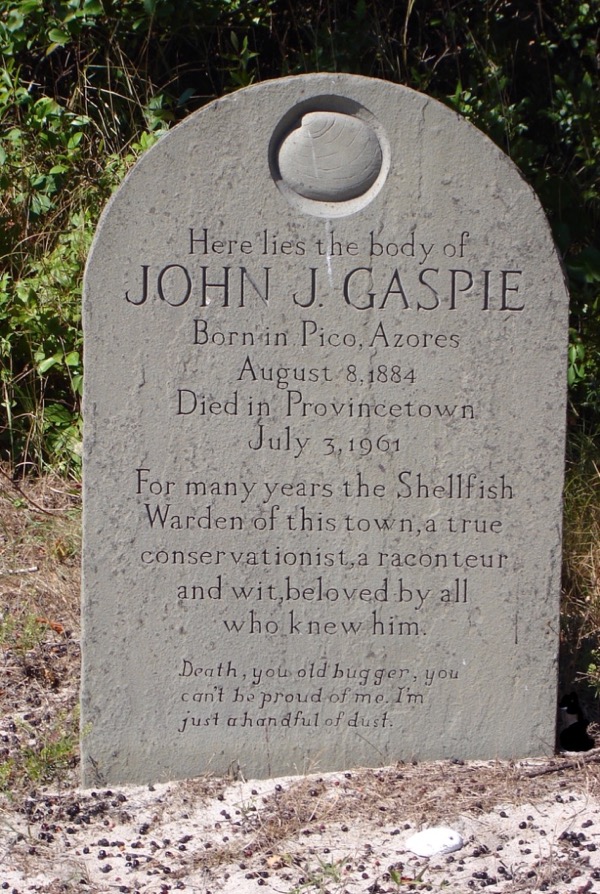

A stroll up the hill from the de Groot plot leads to the grave of Provincetown’s longtime shellfish warden, John J. Gaspie. Born in Pico, Azores, in 1884, he came here as a young man. His legendary harvesting skills (chef Howard Mitcham described Gaspie and himself as nocturnal clam bootleggers) earned him the nickname “Clamdigger.” Later he became, as Mitcham anointed him, Lord Protector of the Quahaugs. When he died in 1961, family and friends honored him with a headstone on which a quahaug is elegantly sculpted in bas-relief. The stone’s inscription, recognizing Gaspie as “a true conservationist, a raconteur and wit, beloved by all who knew him,” and its accompanying tombstone humor, is a work of art in its own right.

Mitcham, whose 1975 Provincetown Seafood Cookbook was dedicated to Gaspie, wrote, “If you scratch a quahaug out of the sand on Provincetown’s clam flats you can probably rest assured that the ghost of John J. Gaspie will be watching you from the great beyond. If a still small voice says to you, ‘That quahaug’s too little, put him back!’ you’d better do so pronto.” Where visitors to other graves mark their pilgrimages with small stones, John J. Gaspie is remembered with clamshells.

Across Cemetery Road, which divides the Alden sections from Hamilton and Gifford, a life-size dog rests, protectively and attentively, with paws outstretched, on the grave of G.B. Smith. Master Mariner Gamaliel Bowley Smith, the son of England-born Mark Smith and Truro-born Ruth Cobb Brown, was the captain of the passenger steamer George Shattuck that plied the waters between Provincetown and Boston twice weekly beginning in 1863. Owned by Joshua and Gideon Bowley, the vessel docked at the end of Court Street, at Bowley’s Wharf, renamed Steamboat Wharf.

Mystery surrounds G.B. Smith’s grave, dated 1874. No one who is buried in the plot died that year, though with the arrival of the railroad in 1873, steamship service was discontinued the following year, 1874. By 1880, Smith and his wife, Sarah, were living in Boston where they both died months apart in 1888. Could the 1874 date correspond to the last voyage of the Shattuck and Capt. Smith’s departure from his hometown? His will, which mentions the upkeep of his grave, makes no mention of the dog. Was it a faithful companion?

Once we are drawn in by a headstone’s aesthetics, it becomes a portal to knowing more about those people no longer among us. Ars longa, vita brevis.