Fishing is mostly a solitary pursuit. Apart from those momentary accolades heard when you arrive home with a nice striper, in fishing there are rarely commentators watching from the sidelines.

But it does have its memory-making interpersonal moments. Many of them involve family. Recently, I watched as two of my under-10 grandkids cast their lures patiently for 90 minutes in a cold, blustery rain. Despite their lack of success at catching anything, I knew this was big: they were taking a first step towards becoming true fisherpeople.

That moment reminded me of one that happened over 20 years ago. I was in Truro to spend some time with my old friends Ray and Lee Elman and their precocious seven-year-old son, Evan, a smart, funny kid who loved to belt out songs and show off the latest dance steps. He was at ease on the beach, where even though he was the smallest kid among his many pals he always seemed to be the leader.

It was a late August day at Ballston Beach. A day without the daunting brilliance of June and July’s skies, with the sun maturing into more mellow, golden tones. The heat was still there, but the frantic, more desperate feeling of early summer had dissipated. By then, fish had been caught, waves conquered, friends made.

Sometime in the early afternoon, the tide having turned to incoming about an hour before, I grabbed my rod and took a stroll to check out what might be happening beyond a long point of beach jutting eastward out to sea.

When I got to the sandy point, I saw it was acting like a breakwater. Tucked just inside its arm was a large school of stripers and bluefish feeding on a frenzied pod of tinker mackerel. They were moving fast, so I headed back to Ballston to keep in front of the blitz for as long as possible.

As expected, the fish followed me back, surrounded now by a raucous cloud of birds diving to pluck tinker meals from the sea. The six-inch mackerels were darting close enough to shore that scores of them were landing on the beach, where Evan and his pals frantically tried to “save” them by returning them to the sea — and back into the maws of marauding bluefish.

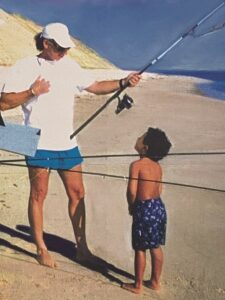

Wanting to keep the kids from wading into the middle of a bluefish blitz, I cast into it, hooked a big bluefish, and handed Evan my rod. It was way too big for him, but, undaunted, he figured out how to put the butt of the rod between his legs and work the reel between them. When we finally dragged the fish onto the beach, his buddies broke into a loud cheer.

“Another one, another one,” Evan sang, while his friends called out, “Can I try? Can I try, too?” Evan cast his pals a quick look. “Sure!” he agreed. So, I made another shallow cast and, not bothering to wait for the strike, handed the rod to one of Ev’s friends saying, “Reel!”

The feeding frenzy, now involving children as well as birds and fish, continued until every boy and girl had reeled in a fish, each conquest eliciting the same happy cheers.

As the fishing began to wind down, one of Evan’s friends looked at me, then looked at Evan. “Who is that man?” he asked.

I looked at Evan, wondering how he would answer that tricky question. Evan’s arms were bent, palms facing up, his shoulders shrugging forwards in that universal I-have-no-idea posture. “He’s … he’s … he’s … my ancestor!” he blurted out, loudly enough for everyone on the beach to hear.

At his bar mitzvah a few years later, I related this story to his family and friends, adding how honored I’d been to receive what remains to this day the highest compliment ever bestowed upon me.