In Wellfleet’s Duck Creek Cemetery, three remarkably well-preserved colonial headstones with classic iconography are a tangible reminder of the John Greenough family. The stones, like too many in Cape Cod’s cemeteries, speak of the sadness of young lives lost, but they offer no hint of the drama that engulfed the Greenough family and the Outer Cape in 1774.

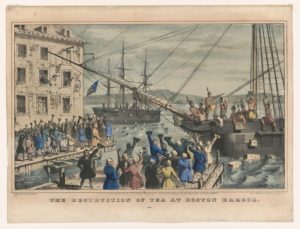

On the stormy morning of Dec. 11, 1773, when the brigantine William, bound from London to Boston, ran ashore near Race Point, one might have forgiven the townspeople for thinking it a routine event, that the William was yet another victim of the treacherous Peaked Hill bars that had claimed countless vessels and lives over the years. Routine, that is, until its cargo was identified. In addition to carrying streetlights for Boston, the William — one of a convoy of seven ships destined for Atlantic ports — was laden with British East India Company (EIC) tea from China. Of the four vessels due to arrive in Boston, the Beaver, Dartmouth, and Eleanor had managed to outmaneuver the storm, anchoring in the harbor where, on Dec. 16, their cargo of 342 chests of tea touched off a political protest that came to be known as the Boston Tea Party.

After the destruction of the tea — the protest ignited by oppressive taxes and the subsequent decision by colonists to boycott tea, over which EIC had a monopoly — all that remained of the shipment bound for Boston were the 58 chests aboard the William, amounting to 12,000 pounds of tea.

Residents of the Outer Cape, with their long, cherished tradition of salvaging cargo from wrecked vessels for personal use or profit, participated in rescuing the tea, not fully understanding how unpopular the rescue would be. At the heart of the erupting anger and unrest was the question of whether the “detestable” tea, on which the tax had not yet been paid, could, in good conscience, be consumed or resold or must be boycotted. Was it the tea itself that was odious, or was it the tax on the tea? After all, tea-loving colonists, including Cape Codders, regularly purchased their favorite beverage smuggled in from Holland, on which no duty was paid.

The central figure in the controversy was a Wellfleet resident named John Greenough, whose father, the prominent Boston merchant Deacon Thomas Greenough, was a member of the Committees of Correspondence, groups appointed to provide colonial leadership in response to British policy. At the behest of the Loyalist Clarke family, distant cousins and owners of the William, John Greenough organized the salvage of the cargo and rescue of crew members at Provincetown, engaging locals to assist with the recovery and paying them with tea from a damaged chest. For his efforts, Greenough kept two chests of tea, a portion of which he sold to Willard Knowles (1711-1786), Eastham’s militia colonel, and Provincetown Selectman Stephen Atwood (1733-1802), both of whom, like Greenough, supported the cause of American liberty.

Cape Codders were sharply divided about the unexpected windfall of untaxed tea. Those who eschewed EIC tea regardless of its tax status targeted the men. Atwood’s home was raided and his tea burned. Residents who purchased the tea and laborers who had aided the salvage efforts were also harassed.

Other townspeople, however, were more than happy to purchase tea as word of its availability spread, arguing that no duty had been paid to enrich government coffers. Knowles, who was maligned by some as an enemy and untrustworthy, was protected from the anti-tea mob by his prominence in the community. Greenough, accused of selling out his country, defiantly tried to defend himself, and as the tumult of 1774 waned, managed to reconcile with both family and neighbors by apologizing for his involvement with the “cursed” tea.

Born in 1742, John Greenough had earned his B.A. from Yale in 1759 and his M.A. in 1762. In 1763, he was awarded a courtesy degree, known as an ad eundem, from Harvard. In 1766, he married Mehitable Dillingham (1747-1798) of Harwich and soon thereafter arrived in Wellfleet, where he opened a grammar school for Greek and Latin instruction that continued until the fateful events of 1774. He was also a successful merchant and was appointed justice of the peace. Seven children were born to the Greenoughs in Wellfleet, three of whom — an infant daughter who lived for only a day; a son, John, who died at 19; and a daughter, Abigail “Nabby,” who died at 13 — are buried at Duck Creek. Another daughter, Sarah, drowned when she was 20 after falling from a vessel bound from Boston to Wellfleet.

After returning to the good graces of his neighbors, John Greenough again took an active role in the affairs of the town, serving in the General Court and appointed in 1778 by the Board of War to secure the “appurtenances” of the British man-o-war Somerset, wrecked in nearly the same place as the William had been five years earlier. By September 1780, Greenough had moved his family to Boston, where he bought a house and land in the North End.

John Greenough did not live to see the patriot cause fully realized. He died in July 1781, just weeks after the death of two-year-old Mehitable and the birth of his eighth child. John’s widow, Mehitable, returned to Wellfleet, where she is listed as the head of household on the 1790 census. Tragically, her son John and daughters Nabby and Sarah had all died within six months of one another, between December 1788 and June 1789. In 1798, just two days after the death of another teenage daughter, Mehitable Greenough died, broken-hearted perhaps by her compounded losses. Of her eight children, only two sons, David and William, survived her.