A bronze tablet attached to a boulder in Eastham’s Cove Burial Ground is one of the few tangible reminders of the Ralph Smith (or Smythe) family, who arrived in Eastham from New Hingham, where Ralph was a founding settler. Robert Charles Anderson, the foremost authority on the arrival of nearly 20,000 primarily English immigrants between 1620 and 1640, notes that Ralph Smith, born about 1616, likely came over as a servant from old Hingham, settling first at Charlestown, then at Hingham by 1637, and finally at Eastham by 1653, where he took the oath of fidelity in 1657. Though Cove’s earliest graves are unmarked, it seems certain that numerous members of the Smith family are buried in the historic cemetery.

Ralph’s marriage is shrouded in conjecture. Family folklore offers that he was married first to Elizabeth (or maybe Rebecca) Hobart of Hingham. He had seven children, the first dying in infancy. After being widowed, Ralph is said to have married Grace (possibly Lewis), the widow of Thomas Hatch of Barnstable, family historians speculate. Anderson notes, however, that Hatch’s wife had died by 1662 and that Grace is Smith’s only wife in the records, making her the likely mother of his children.

Until 1763, Eastham, originally known as Nauset, included the neighboring area that is now Wellfleet. Anyone who has enjoyed Wellfleet’s Great Island peninsula trail has, no doubt, stopped to ponder the remains of the tavern there. Smith family lore and local tradition claim it was owned by Samuel Smith (1641-1696), the eldest of Ralph’s surviving children, and a successful Eastham merchant.

The sea was then the mainstay of Wellfleet’s economy, and its open and deep harbor, indented with shallow creeks, was ideal for the herding of whales, mostly blackfish, also known as pilot whales, chasing feed in coastal waters. Driven ashore (the town seal depicts a beached blackfish), whales were brought to Great Island for “trying out.” While taverns were generally situated on well-traveled byways, the remote location of Smith’s tavern — with no overland access — suggests that it served whalers arriving by boat.

In spring 1970, archeologists from the National Park Service and Plimoth Plantation confirmed foundations on the site had supported rooms and cellars. Thousands of artifacts, including ceramics, pipe stems, and eating and drinking utensils, indicated that the site had been a tavern that operated — based on ceramics dating — between 1690 and 1750. Upon Samuel’s death in 1696, and with the premature death of 24-year-old Samuel Jr. in 1692, the tavern was said to have passed to the senior Samuel’s brother Daniel and, thereafter, to Capt. Samuel III (1691-1768), the enterprising “inn holder” during its heyday.

The tavern was a microcosm of the man’s world of Puritan New England. While men transacted business and conducted the affairs of the town, married women like the elder Samuel’s wife, Mary Hopkins, a daughter of Mayflower passenger Giles Hopkins (also buried at Cove with his sister, Constance), and Grace Smith were excluded from owning property and from formal participation in public life. They were not, however, without influence. Through managing the home and raising God-fearing children, they were tasked with nurturing and preserving the family and community.

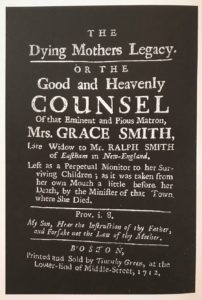

It is rare to read reminiscences of a Puritan woman, but in 1710, as the 96-year-old Grace lay dying, her minister, the Rev. Samuel Treat, made a customary visit to her bedside. As family lore tells it, Grace, who had been widowed since 1685, asked Treat to record her last words and Biblical teachings that they might be passed down to her surviving children. Treat took copious notes of his visit and later chose Biblical verse to complement her gentle and merciful voice, a voice that would have been in stark contrast to the fire and brimstone heard from the pulpit. In 1712, Treat had Grace’s “counsel” published by Timothy Green, an early Boston printer and bookseller.

Said to be the only recognized religious writing by a Puritan woman in colonial America, The Dying Mothers Legacy; or The Good and Heavenly Counsel of That Eminent and Pious Matron, Mrs. Grace Smith included 20 maxims and two poems, the first of which opens with the line My children dear, whom I did bear, suggesting that Grace was, in fact, the mother of Ralph’s children. Additionally, as was the custom of the time, the name Grace reappears in the records in 1676 as a daughter of Samuel and Mary, and again in 1725 as a daughter of Samuel III and Abigail Freeman, thus honoring the matron.

More than 300 years after delivering her soliloquy to Mr. Treat, Grace’s counsel — stay humble, find contentment, keep your promises, live for today, judge not, gather riches of which the world cannot rob you, and to those who are given much, much is expected — is a timeless creed to live by.

Editor’s note: Amy McGuiggan’s story about the Rev. Samuel Treat was published on March 11, 2021.