On his first excursion to Cape Cod in October 1849, Henry David Thoreau stopped in Cohasset to view the gut-wrenching aftermath of the wreck of the brig St. John, carrying destitute refugees from Galway to what should have been a new life in America. Caught in a storm approaching Boston, the St. John sought refuge in Scituate, only to be dashed on the Grampus Ledge. Of the more than 160 people on board, only an estimated 20 survived.

Resuming his journey, Thoreau reached the Great Beach, where the only humans along the lonely stretch were wreckers, who made a living — or at least a sideline — off shipwreck salvage, “looking for driftwood and fragments of wrecked vessels.” From one of those wreckers, he learned about another shipwreck, that of the full-rigged Franklin, lost at Newcomb Hollow on March 1.

Sailing from Deal, England under the command of Capt. Charles Smith, the Franklin was a Boston vessel owned by John W. Crafts and James W. Wilson. Carrying passengers and cargo, the Franklin appeared to have ventured too close to the bars off Wellfleet on that fateful Thursday morning, and though the winds were moderate, the weather fair, and the anchorage good, she slipped her chains and was driven ashore, breaking into pieces. Among those who witnessed the tragedy was John Young Newcomb, the “Wellfleet Oysterman” of Thoreau’s Cape Cod. Historian Edward Rowe Snow writes that 33 souls were aboard the Franklin, 11 of whom — including the captain and first mate — perished when their lifeboat lurched in the heavy surf and pitched them into the breakers. Those who stayed with the Franklin were rescued. The ship’s valuable cargo, including wool, linseed oil, nutmegs, and a coarse, heavy linen known as tow cloth, was strewn along the shore. At the time of Thoreau’s October visit, the sea was still heaving up treasure for the Wellfleet wreckers.

Were it not for a valise, hauled in from the surf by Isaiah H. Hatch, the Franklin may have been relegated to history as yet another vessel gone to a watery grave and not the focus of a sensational conspiracy case that played out in a Boston court.

Capt. Isaiah Holbrook Hatch was born in 1798 to George Hatch and Drusilla Parker of Truro. In 1820, he married Eliza Smith Young of Wellfleet, the daughter of Benjamin Young and Elizabeth Arey. By all accounts, Hatch, who had owned the vessel Aurora and spent 30 years as a seaman, was a respectable citizen and a devout member of the Congregational Church, where he owned a pew. At the time of the Franklin wreck, he was retired from the sea, farming and making the most of whatever the tides cast up.

Having retrieved the water-logged valise, Hatch carried it home, where he dried and read the letters contained within. He quickly realized that the valise belonged to Capt. Smith, and that the letters, signed with the initials J.W.C. and J.W.W. — John W. Crafts and James W. Wilson — revealed a plan to deliberately scuttle the Franklin to collect insurance money. Days later, Hatch contacted Truro-born Capt. Ebenezer Davis, a retired mariner who knew the coast intimately. Then living in Boston and working as a marine inspector, he arrived in Wellfleet as the underwriters’ investigator. The valise was delivered to Davis, who delivered it to prosecutors.

In mid-April, the trial for conspiracy commenced. Despite testimony by numerous witnesses, including Isaiah H. Hatch, and the damning “wrecking letters” being admitted into evidence, the proceedings came down to a he said-he said between Wilson and Crafts. Wilson, who pleaded not guilty to two charges and guilty to one — while claiming to have been a patsy for the mastermind Crafts — became a government witness. Crafts denied all charges, asserting that Wilson alone had written the letters and that he was a perjurer and a swindler. After a 30-day trial and one day of deliberation, Crafts was acquitted on all counts. Wilson also did not serve any time.

Civil proceedings were initiated to collect the Franklin’s insurance, said to have been twice what the vessel and cargo were worth. Despite daily newspaper coverage of the trial, virtually nothing was said about the lives lost.

Included in the salvage from the Franklin was nursery stock bought in England and Scotland by a South Boston man named Bell, who hoped to establish the varieties in New England. Thoreau references the pear and plum trees that he saw growing in the garden of Isaiah Hatch, specimens from the Franklin, and notes that Hatch’s turnip seed also came from the wreck. Might that seed have been the source of the famous Eastham turnip, believed by some to be related to the Scottish turnip?

Isaiah H. Hatch lived a long life tinged with heartbreak. Five daughters and one son were born to Isaiah and Eliza, who outlived all their daughters. Two of them, Elisa and Minerva, died within days of each other in 1865 of typhoid fever. The son, Isaiah Adams Hatch (1832-1894), who was exactly four feet tall, became a well-known traveling merchant who enjoyed the hospitality of friends from Truro to Hyannis. Known as “The Colonel” and “The Little Man,” his sorrowful story of having lost his mother and five sisters was told in broadsides, printed in 1879 and 1889, which he sold for five cents along with other goods.

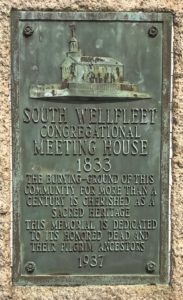

Isaiah, Eliza, Isaiah Jr., and Minerva Hatch rest together in a family plot in the South Wellfleet Cemetery on Route 6. First laid out in the 1770s, the cemetery was the site of the Congregational Meeting House (Second Congregational Society), built in 1833. No longer active by 1917, the building was sold in the 1930s and moved to Wellfleet village, becoming the Town Hall until it was destroyed by fire in 1960.

Editor’s note: “The Little Man” broadsides can be viewed online at Brown University’s John Hay Library Harris Collection of American Poetry and Plays — Broadsides.