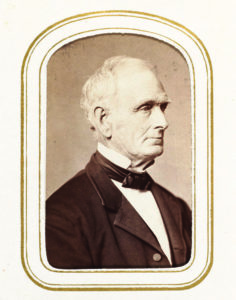

Henry David Thoreau, enjoying his fourth and last visit to Cape Cod, wrote in his journal dated June 21, 1857 that he had “called on Mr. Atwood, the Representative of the town and one of the commissioners appointed by the legislature to superintend the experiments in the artificial breeding of fishes.” This was the esteemed Capt. Nathaniel Ellis Atwood, who, by dint of an insatiable curiosity and keen powers of observation, overcame humble beginnings as a fisherman’s son to acquire expertise in the natural sciences, his discoveries earning him recognition from scientists.

The first of nine children, Nathaniel was born in Provincetown in 1807 to John Atwood and Polly Butler. John, born in 1784, was the son of Samuel Atwood, one of eight documented Revolutionary War patriots (including cousin Stephen Atwood) whose graves in the Winthrop Street Cemetery have been marked by the Daughters of the American Revolution.

When Nathaniel was 11, John moved the family across the harbor to Long Point to be closer to the fishing grounds. He built the first dwelling there and the point’s only wharf, whose pilings still protrude from the sand. Joined by other families, including those of Eldredge Smith and Prince Freeman, the flourishing community engaged in seine fishing and salt making.

At its peak in the late 1840s, Long Point was its own school district and had a population of 200, which steadily decreased in the 1850s. By the outbreak of the Civil War in 1861, only a few structures remained. Many of the dwellings were floated across the harbor on scows and can now be identified by their blue and white enamel markers. Nearly four decades after his father had become Long Point’s first resident, Nathaniel Atwood was one of its last, removing to town in 1856. His “floater” settled at 5 Nickerson St. in Provincetown’s West End.

At age 13, having shore-fished with his father for two years, Nathaniel went to sea as a cook on a vessel bound for Labrador. By 21, he was master of his own vessel, and, in 1829, he married his Long Point neighbor, Maria Smith, daughter of Eldredge and Experience Smith. Five children were born to the couple before Maria’s death from dysentery on Aug. 1, 1849. Their son John, born in 1837, died of the same ailment two days before Maria, as did Maria’s mother, Experience, on Aug. 8 and her father, Eldredge, on Aug. 19.

A cholera epidemic had swept across Boston during the summer of 1849, and it appears that dysentery and cholera — both spread by contaminated food and water — also raged on the Cape. The following October, Nathaniel married Louisa Russell Blake, the mother of five-year-old James Henry Blake. Nathaniel and Louisa had five children, two of whom, twins Charles and Lizzie, died in infancy.

Capt. Atwood was a master of the whaling, mackerel, dogfish, halibut, and cod fisheries and of coastal trade until, at age 60, he “coiled up his lines and quitted going vesseling,” turning his attention full-time to the manufacture of medicinal cod liver oil. His civic service included two terms as representative to the legislature (1857-1858), a term as state senator (1869-1871), bank trustee, three years as a school committee member, and his appointment by the governor to study the propagation of fish as a potentially lucrative industry.

By the early 1840s, Atwood’s knowledge of the fishery attracted the attention of the scientific community, particularly physician and naturalist David Humphreys Storer (1804-1891), whose field studies culminated in the 1867 publication of A History of the Fishes of Massachusetts. In his introduction, Storer wrote that “during the last six or eight years, no individual has rendered me such essential assistance as Captain Nathaniel E. Atwood of Provincetown. For nearly thirty years a practical fisherman, thoroughly acquainted with the habits of most of our fishes, and willing and ready to do all in his power to advance my wishes, he has placed me under obligations which I cannot express.” Storer added that Atwood was “the best practical ichthyologist in our State.”

Atwood became a popular lecturer on the topic of fish, sprinkling his talks with colorful homespun anecdotes. Among his colleagues was the Swiss-born naturalist and Harvard professor Louis Agassiz, who visited Atwood on Long Point and for whom Atwood later procured a right whale skeleton for Harvard’s Museum of Comparative Zoology. Thoreau, during his stay at Walden Pond, had collected specimens for Agassiz; one wonders if these intersecting lives were a topic when Atwood met Thoreau. Young James Henry Blake, no doubt inspired by his stepfather’s contributions to natural science, began studying with Agassiz in 1864. As a budding zoological artist, Blake illustrated specimens from Agassiz’s research and chronicled the pursuit and capture of the right whale whose skeleton is still on display at Harvard.

At the height of Capt. Atwood’s fame, his son, Nathaniel Jr., won his own acclaim. After embarking on a whaling voyage in March 1867 under the younger Atwood’s command, the Provincetown schooner Cetacean sighted the waterlogged British brig Lone Star, which had floundered for 35 days en route from Liverpool, Nova Scotia to Demerara (Guyana). Seven other vessels had passed, unable to render assistance. Nine days later, the nine crewmen of the Lone Star disembarked safely at Barbados, with Capt. Atwood refusing any compensation for the rescue. A vote was taken in the House of Commons awarding Nathaniel Jr. a mounted, leather-sheathed telescope for his humanity and kindness to the master and crew of the disabled ship.

In 1886, upon the death of Nathaniel Ellis Atwood, whose life spanned Provincetown’s golden era, James Gifford paid tribute to him as a man of a “serene, cheerful temper, unassuming in manner, charitable to faults, public spirited and benevolent.” His whole career, noted Gifford, was characterized by “unselfishness, gentleness and integrity that was unswerving. The death of no man in Provincetown, in this generation at least, produced more general or sincere regret. His character and memory are a legacy to the people of this town.”