The holiday season is upon us and, for many, this is a time when grief hits hard.

This year, as we continue to isolate from one another because of the pandemic, there are new layers of loss. But if this is an opportunity to grieve more fully, that’s something experts say we’ve needed to do for a long time.

“The tragedy of Covid has brought us new grief, and it has also opened old grief for many,” said Clair Willis, a clinical social worker who has worked with people in bereavement for over 20 years. “As a result, the word ‘grief’ and the complicated emotions we feel when we are grieving are becoming more acceptable.”

Still, the expectation of holiday cheer can make it difficult for people to seek out — or give — comfort, said Bill Gately, a licensed mental health counselor with a specialization in loss and bereavement.

“People whose sadness increases during the holiday season often step into the background,” Gately said, “because they don’t want to hurt anyone else’s festive mood.”

Gately has observed that this can come at a high price. He has worked with people who were healthy when a spouse died but declined afterwards. “They would lose their enthusiasm, their desire to live,” he said.

Yet, Gately said, in his work with survivors, “when we asked them how they were doing, they’d say, ‘I’m doing fine. It’s lonely, but I’m getting there.’ And that’s the answer we really want to hear. It takes us off the hook from having to listen and from not knowing what to say.”

Gately, who owns Provincetown’s Gately McHoul Funeral Home, has witnessed first-hand people’s discomfort with grief. He notes that, when we encounter someone who is mourning a loss, our instinct is to try to find something positive to say.

“That may be ‘He is in a better place now’ or, when someone dies after a long illness, ‘She is no longer suffering,’ ” Gately said. “And when you’ve lost your mother at 98, a friend might console you with ‘You’re lucky to have had her for a long time’ — all of which may be true, but by trying to create happier thoughts for people, we are not allowing them to be where they are at.

“The best support we can give a person in grief is just to listen,” Gately said.

It can also help to talk about the person who is being missed, said Kim Mead-Walters, co-founder of Sharing Kindness, a Cape Cod nonprofit focused on suicide prevention and grief support. “If you are looking to support a friend who is grieving, talk about their loved one — say their name,” Mead-Walters said, adding that, by naming lost loved ones, we are showing our awareness of their significance.

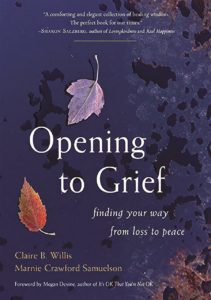

“Some of grief’s feelings, such as sadness, confusion, anger, or anxiety, are deeply uncomfortable,” said Marnie Crawford Samuelson, who is Willis’s co-author of a new book, Opening to Grief: Finding Your Way From Loss to Peace (Dharma Spring, 2020). But healing, she said, comes from allowing yourself to make room for all of your feelings — “It’s because we love deeply that we grieve.”

“When we reframe grief as love, the challenge becomes not how to get through the holidays, but how to express our love in a different way,” Willis said. “We have to find new ways to bring the love we feel along with us as we live with our loss, because if we suppress our sorrow, we are also suppressing our joy.”

Opening to Grief suggests ways to embrace grief and make it into a meaningful experience: connecting with nature, writing letters to your lost loved one, or keeping a gratitude journal.

Grieving authentically, Gately said, is the only way to honor your deeply personal experience. “The stages of grief by Kubler-Ross are the worst thing we’ve taught people,” he said. “Many come to me struggling because they feel that they are not grieving in the right way. Everybody grieves differently. Everybody needs something different.”

Dawn Walsh agrees. Walsh, who lives in Provincetown, is a death doula. She accompanies the terminally ill through the process of dying and supports those left behind as they mourn. She encourages people to think about grief as an ongoing relationship with a loved one.

“When you have experienced a significant loss, you’re going to have various feelings about that for the rest of your life,” she said. “There is no closure that you have to get to.”

Walsh encourages people to create rituals and share stories about the person they have lost. Adapting cherished holiday traditions so that the loved one remains included, she added, “can become a way to honor that person.”

Mead-Walters found this to be true for her own family. “The Christmas holidays had always been my favorite,” she said. “That changed when my son Jeremy died. I was filled with dread, until we made a new family tradition.”

Family members take the money they would have used to buy a gift for Jeremy and, instead, make a donation in his memory. Then they put information about their donations in a box with Jeremy’s name on it under the tree.

“On Christmas morning, we open the box and share our memories of Jeremy, and why we chose to donate to each specific charity,” she said. “This keeps Jeremy present, and, while I miss him, I no longer dread Christmas morning without him.”

That experience of grief transformed is what Willis hopes might come for people who are feeling more pain this year. “If we can allow grief to open our hearts deeply,” she said, “we can join with one another in both our suffering and our joy.”