WELLFLEET — If you search for Abbe Seldin in the archives of the New York Times, you’ll find four articles.

The first, by Leslie Oelsner, appeared on Feb. 1, 1972, when Seldin was a 15-year-old sophomore at Teaneck High School in New Jersey, just five miles from the bridge to Manhattan. “Teaneck Girl Sues to Join High School Tennis Team” was the headline.

Seldin, with help from the American Civil Liberties Union, had filed suit in U.S. District Court to be allowed to try out for the boys team because there was no girls team. This was five months before Congress passed Title IX, the federal law that prohibits sex discrimination in education programs, including school sports. Seldin’s A.C.L.U. volunteer lawyers were two young Rutgers University Law School professors, Annamay Sheppard and Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

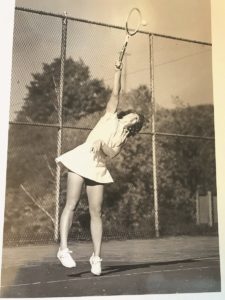

“I was a normal high school kid, playing tennis on my own in tournaments around the New York area,” said Seldin, now 64, last week at her home in Wellfleet. Her father, Arthur Seldin, had inspired her love of tennis. “He was a really good player,” she said. “When he came back from World War II, he won all the tournaments around metro New York. He played number one for N.Y.U., captain of the team for three years. Dad was great.”

Abbe was not especially political at the time. She just wanted to play tennis and be part of a team. She was ranked 22nd among 15- and 16-year-olds by the Eastern Lawn Tennis Association.

Gender discrimination in sports was a hot issue. The state officials governing interscholastic sports at the time rejected co-ed tennis because of the “substantial practical, psychological and physical reasons for separating girls and boys on the high school level in competitive sports and in tennis in particular.” The following year saw the celebrated “Battle of the Sexes,” in which Billie Jean King defeated Bobby Riggs, a former world number-one player, who had bragged that he could beat any woman on the court. Ninety million people watched the match on TV.

King was Abbe Seldin’s favorite player.

“Martina and I are the same age,” Seldin said, referring to tennis star Martina Navratilova. “But I really liked Billie Jean. I didn’t care much for Margaret Court Smith. I remember the original nine in the Virginia Slims. It’s 50 years since women started the W.T.A. and had their own tour.”

Seldin and Ginsburg never actually met, but they had many long phone conversations. In her court brief for Seldin’s case, Ginsburg argued that, in a sport like tennis, gender is “as irrelevant a factor as is race, religion, national origin, political beliefs or hair color.” The lawyers maintained that discrimination on the basis of sex violated the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of equal rights, an argument that Ginsburg would later champion successfully in a series of landmark Supreme Court cases.

The second time Seldin appeared in the Times was on April 22, 1973, while her case was still pending. An article about the parents of young tennis stars playing in a tournament on the Upper East Side, by Charles Friedman, reported that “Mrs. Shirley Seldin, another Jerseyan, said she gets ‘choked up’ and ‘my heart misses a few beats’ when her daughter, Abbe, plays.”

“Mother didn’t play,” said Abbe last week, “but she knew everything about tennis and could analyze it.” She also fully supported her daughter’s desire to join the boys team at Teaneck High, as did the school’s tennis coach, Arthur Christensen.

Two months after that mention, Abbe was in the Times again, in Parton Keese’s “People in Sports” column on June 28, 1973.

Keese reported that Judge Leonard Garth, who was presiding over the case, had offered to referee a match between Abbe, who was now 16, and three top male players on the school team. Garth was an avid tennis player. “I’ll do anything to dispose of this case,” he told the Times. “I’ll take her on myself if I have to.”

Before that could happen, the case was settled out of court in Seldin’s favor. She tried out for the team and made it. But by then, the supportive Coach Christensen had left, and the football coach was put in charge of tennis.

“He ran it like a football team,” Seldin said. “Basically, he had a really bad attitude towards me. We started practices and he had us do football drills. You had to climb stairs using your arms and somebody would hold your legs, to build up your upper body strength. I made it to the top of the stairs and then the guy dropped me. I fell down the stairs on my chest and front and had the wind knocked out of me. And I just left. I went home to my mom and I said, ‘It’s not for me. We gave it our best shot.’ And my parents said that was absolutely fine.”

She went back to working with private coaches and playing at the Stadium Tennis Club in Harlem, then went on to play tennis at Syracuse University. She is not bitter about what happened in 1973.

“The important thing to remember is this was the cusp, the beginning of Title IX, which was huge,” Seldin said. “I was able to benefit the very first year, when I went to Syracuse. I went to the chancellor of the university and the director of women’s sports and said there needs to be athletic scholarships for women.” She was one of the first women at Syracuse to get one.

Seldin still plays tennis two or three times a week, at Oliver’s Clay Courts in Wellfleet and at Willy’s in Eastham.

“I’m very proud to say I have two brand-new titanium knees and they’re excellent,” she said. “I’m just running like a kid. To be able to run again, to move side to side — it’s a miracle.”

Her fourth appearance in the Times was last week, on Sept. 28, after Justice Ginsburg’s death, in a story by Andrew Keh. That piece, and another about her in USA Today, related her painful experience on the stairs at Teaneck High.

“When all this came out recently in those articles, I posted it on Facebook for my graduating class,” Abbe said. “All these football players and tennis players I hadn’t heard from for years wrote back about how horrible that coach was and how many of them had quit the team because of him. All the guys remember him. He abused the football players horribly. It brought me a sense of validity. I was no chicken.”

Edward Miller is a member of the Teaneck High School Class of 1966.