PROVINCETOWN — On Aug. 5, 1910, after three years of construction, Provincetown’s Pilgrim Monument, commemorating the first landing place of the Mayflower Pilgrims, was dedicated by President William Howard Taft atop High Pole Hill. Almost three years earlier, on Aug. 20, 1907, in an elaborate Masonic ceremony, the cornerstone of the monument had been laid by President Theodore Roosevelt, who arrived in Provincetown aboard the aptly named presidential yacht, Mayflower.

It was a source of great pride that, during the three years of construction, no workers involved in the project had been injured or killed. There was, however, one casualty, a freak accident that marred the celebratory atmosphere on dedication day.

The Pilgrim Monument had been years in the planning. It was first conceived in 1892, when the Cape Cod Pilgrim Memorial Association was formed for the purpose of erecting “some suitable structure upon Provincetown’s Town Hill.” Architect Willard Thomas Sears based his design on the Torre del Mangia in Siena, Italy. It was made of granite from Stonington, Maine, blocks of which were brought to Provincetown by barge and unloaded at the waterfront. From there they were transported across Commercial and Bradford streets to the base of High Pole Hill.

Were a Provincetown resident from 1907 to reappear in 2020, the deep scar now visible on the Bradford Street side of the hill — the future site of an inclined elevator providing access to the Monument — would look eerily familiar.

In 1907, a similar swath was cut for a railway to haul the granite up the hill in heavy steel motorized cars. By early August 1907, the foundation work that began in June had been completed, and in mid-June 1908 the tower began to rise atop the dune.

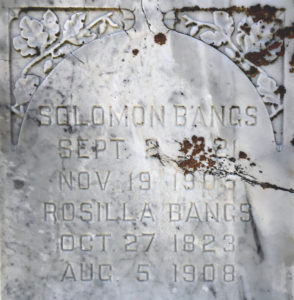

The story goes that during a thunderstorm on Aug. 5, 1908, one of the motorized cars, left empty on a level area atop the hill, was set in motion by a lightning strike that loosened its tether. Though a report in the Boston Herald disputed the lightning story, it did not change the tragic outcome. The runaway car gained velocity, and its momentum carried it through a protective timber barrier at the bottom of the hill and into the path of Rosilla (Rich) Bangs, the 84-year-old widow of Solomon Bangs, killing her instantly.

The Herald reported that a passerby who saw the car hurtling down the rails tried to warn Mrs. Bangs, to no avail. After hitting her, the car continued its rampage, crossing the street and crashing through the fence at Enos N. Young’s home at 129 Bradford St. before coming to rest in a neighbor’s yard. Rosilla’s death certificate noted the cause as a “concussion of the brain and multiple injuries accidentally received by breaking of cable and descent of the supply car for the monument on Town Hill.” Ironically, the town clerk who filed the certificate was none other than Enos N. Young. Just a year earlier, Rosilla had shaken the hand of President Roosevelt at the laying of the cornerstone.

The marriage of Rosilla Rich to Solomon Bangs Jr. continued a long tradition uniting the Rich family of Truro and the Bangs family of Provincetown. Both families have roots in Eastham, Richard Rich arriving by 1665 and Edward Bangs, who arrived in Plymouth in 1623 aboard the ship Anne, having been one of Eastham’s pioneers in 1645. In Provincetown, the family name is now immortalized on Bangs Street, once a narrow winding lane where the family owned considerable tracts.

In 1848 Solomon Jr., a sailmaker and wholesale fish dealer, built his wharf in Provincetown’s East End, and by 1852 he was a pioneer of inshore weir fishing — also known as trap fishing — following a traditional method long used by Native Americans. In the early 1890s, when Solomon’s eyesight began to fail, threatening his livelihood, the entrepreneurial Rosilla had an idea. Then a woman of 70, she contacted the Boston company from whom Solomon bought his sail cloth and arranged to have tents made for a summer seaside colony she established near the Truro line on a parcel of Bangs ancestral land once owned by Capt. Jonathan Bangs (1640-1728), an original proprietor of Truro. Bangsville (now Mayflower Heights) was immediately successful and profitable.

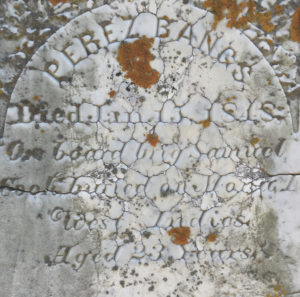

In the Provincetown cemetery, a marble obelisk marks the Bangs family plot, where three generations rest. Inscribed on the obelisk is an epitaph to Perez Bangs (1825-1848), the younger brother of Solomon Bangs Jr., whose death at the age of 23 is yet another reminder of the price paid by so many who followed the sea.

Young Perez, a crewman on the whaling brig Samuel Cook, died at sea in January 1848 and was buried on an island in the Mona Passage between Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. In February, when word of Perez’s death reached Provincetown, his father, Solomon Bangs Sr., chartered — at great expense — the schooner Palestine, owned by Captain Henry Whorf, to recover his son and return him to Provincetown.

Newspapers described the schooner’s voyage as a moving example of a father’s determination to bring his dead son home; one dispatch was poignantly titled “Parental Affection.” But by mid-April the Palestine had returned to Provincetown without Perez, the crew unable to find the spot where he had been buried on the uninhabited island. Sadly, the Bangs family monument also shows that Solomon Jr. outlived his son Perez, born just months before the elder Perez was lost at sea.

Editor’s note: Capt. Henry Whorf (1813-1852) was author Amy Whorf McGuiggan’s third great-grandfather. He died of yellow fever in Haiti.