It was in some ways not an unusual invitation, from one yoga teacher to another: “I have a really special client that I’d like you to meet,” my colleague wrote. “I will be moving off Cape soon, and it is important that I find someone adept to take over for me.” But there was more to it than the usual singing of praises. “This isn’t a normal yoga job. She is 89, like a grandmother to me, and is the most important person I’ve met in my yoga career.”

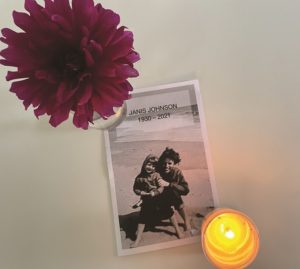

The next week, I met Janis Johnson.

Most of the things you learn when you’re training to become a yoga teacher prepare you for a career in studio settings. Sequencing, adjustments, the movement of an able body, Sanskrit, waivers, ethics. That training does little to prepare you for bodies unlike your own. You work with each other’s bodies, so that everything you learn is inherently biased towards a younger, athletic, more able crowd. There were only five people in my initial teacher training above the age of 30. Even now, after thousands of hours of courses, I have heard a teacher speak only once on yoga and death.

I remember that moment. It was at an advanced teacher training, where Rod Stryker was speaking about what it means to continue a yoga practice over a lifetime. A woman in the crowd who said she was in her late 70s asked, “What should I be doing in my practice at my age and beyond?”

It was clear they’d known each other for a long time — his eyes brimmed with tears as he greeted her fondly and responded, “There is not any one thing you should or should not be doing in your yoga practice, except to simply keep practicing. Practice in any way that you can. Ultimately, we prepare for accepting death.”

Each Wednesday morning, when I arrived at Janis’s house, we would check in: What hurt? Which doctor was she seeing that afternoon? We pored over documents from Spaulding Rehab, talked about her physical therapy regimen, and, most important, what did she want to do?

We had to adjust to the changing nature of her body. She was as healthy as you could wish to be at 89: bright, sharp, wittier than I, and more kind than most. She still had days when pain was too intense to do much but just be instructed in breathing for the entire hour. Or days when the neuropathy in her feet didn’t allow her to walk — when, after she’d been lying down, she wasn’t sure where they were in space. There were other days when we practiced standing balance poses.

After each session, she would close her eyes, take a deep breath, and sigh contentedly. There were many mornings when tears would fill her eyes and she thanked me for “teaching her to breathe and rest.” She was good at finding deep peace in her 10 or 15 minutes of savasana, the final resting posture of a yoga practice.

When we began, I attributed her grace to her personality. We had frank conversations about her body, death, and what comes next. She laughed raucously one day after she said, “I hope I can feel my feet when I get there.”

It wasn’t until her final year of life, when the pandemic hit, that I truly understood what her practices had done for her.

As the rest of us spiraled and panicked, Janis was a lighthouse in the storm. She had a discipline unlike anyone I’ve ever known. Day by day, she kept up with her meditation and breathing practices. An alarm on her new phone went off every 30 minutes to remind her to take five deep breaths. She decided promptly that she needed to know only what was pertinent to her — local and regional news and the lives of those around her.

Janis kept a firm lid on anxiety by acting only on what she could control and letting go of all else. She acted without doubt. She accepted that there was much to let go of. She employed tools of yoga practice that still evaded me.

A few days before she died, we had a session together over FaceTime. We had adapted to necessity and had weekly video chats alongside our yoga sessions. We laughed about our upcoming birthdays and how cupcakes would make it easier to share birthday sweets during a pandemic.

It was that next week, on her 91st birthday, surrounded by cards filled with powerful declarations of love and adoration, that she lay down for savasana for the last time.

In this final moment of acceptance, she surprised us all. I, like many others in her support circle, had somehow believed that I would have this weekly appointment with Janis for the rest of my life. That she said, “Thank you, I love you” after every session not because she, the ultimate yogi, accepted it might be her last, but because she was a loving person. It turned out both were true.