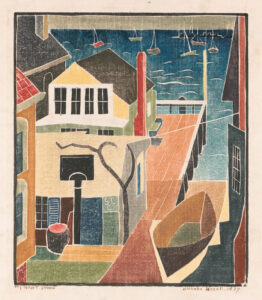

“The gaiety and brilliancy of the flowers surrounding the studio of Blanche Lazzell attract and hold our attention whether we glimpse it from the waterside or through its narrow approach down an unnamed alley. Gay as these surroundings are they find a rival in the fascinating interior of this former fish house, now one of the more attractive spots in Provincetown. It is here that more than a thousand visitors have this summer seen Miss Lazzell’s work: an exhibition of wood block prints, which would draw attention anywhere and in this town with its variety of production stands distinctive by reason of its honest strength and genuine character.”

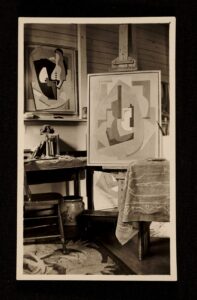

So reported the Provincetown Advocate in 1940. For much of the artist Blanche Lazzell’s life, Provincetown was her happy place, and, tucked within it, an even happier spot, her bayside studio garden of boldly colored annuals. There, in a former storage shack that had housed fishing supplies, she was her most creative and productive. She began painting, printmaking, hooking rugs, and decorating porcelain pieces as soon as she arrived in town in 1915 to study with Charles Hawthorne.

“The sea is wonderful to paint,” she wrote to her sister in that first year. “But don’t think or let anyone think I am here on a pleasure trip. I am getting pleasure out of very hard work. I am getting very encouraging criticisms. Mr. Hawthorne says, ‘go right on painting that way.’ ”

Despite her somewhat conservative nature and upper-middle-class upbringing in the coal country of West Virginia where she was born in 1878, Lazzell was very independent for the time, and as an early cubist, drawn to the new and novel in art. She studied with Fernand Léger and others at the Académie Moderne in Paris, making new American friends there who enticed her to settle afterwards in the new Cape Cod art colony.

Frequent letters to her sisters reveal a woman who relished a sense of freedom she found on the Outer Cape. The other, near constant topic in her letters was her studio flower garden, especially her petunias, which she doted on as if they were beloved pets. “It is a beautiful day,” she reported to her sister in 1932. “We had a hard rain and storm last Friday. It melted every petunia blossom, but they are out again now…. It spoiled the marigolds. I still have snapdragons. The garden has been heavenly this summer. The petunias seem to be so human.”

Lazzell was from a family of means but she had to live frugally on a small stipend most of her life. So, hers was a garden of economy: salvaged wooden containers, barrels, and lard tubs, all swathed in string fishing nets that hid her homespun construction techniques while providing maritime-themed trellising for morning glories and vining petunias, which she reported to her sister reached six feet tall.

In 1927, she wrote to her niece, Frances Reed, “I am now waiting for Mr. Atkins the plumber to come to fix a water line & faucet in the garden — going to have it piped around the chimney. And when I get my next check, I’ll order a soft hose. My elbows are not strong enough to carry water another summer. I think that excuse is enough to have that convenience, don’t you?”

To promote the sale of her artwork, Lazzell held classes and intimate teas at her studio where she served sponge cake, cream cheese and pimento sandwiches, and saltines with homemade beach plum jelly. “I have had four teas since the first of Sept.,” Lazzell wrote in a 1932 letter. “You see my teas cost very little. My flower seeds more than paid for them.”

She enjoyed harvested her seeds for sale as a side gig, especially her petunias with their almost cubist stripes, rays, veins, and splotches. “People everywhere are after my petunia seeds,” she wrote. “I am selling them for 35 cents a package” — around $7 today. Hers were worth it, she explained: “Of course the package is not big but mine are bigger than the ones from the regular florists. And my seeds are more rare for they are my own culture.”

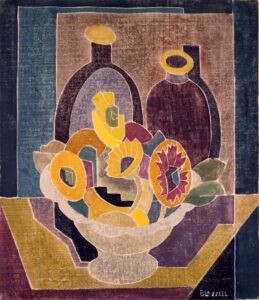

Alongside these practical preoccupations, there was something almost mystical about the garden for Lazzell. “You feel, or what Mr. Hofmann says, ‘you experience’ the flowers, then your subconscious mind does the arrangement,” she wrote to her sister. “We must know and experience, feel to the depths of our soul, the flower, then we have this inner power to do things with it…That is art.”

She knew of her value, and perhaps even her future importance as one of the earliest American abstract artists, especially as a woman. When needing to pay a tax bill in 1932, Lazelle urged her sister to sell some of her prints back in West Virginia. “This is a fine investment for anyone who has the money to spare. For these prints will be worth more than a hundred dollars before you know it and especially when I no longer make them,” she wrote. “And they are admired by the leading modern painters in this country and abroad.”

“She’s definitely at the top of the pyramid now,” says Jim Bakker of Bakker Gallery in Provincetown. “It seems to me that she has eclipsed many of the male Provincetown artists who were more famous than she was during her lifetime, especially at auctions today. When you look at the other people working in the white-line printing style, she had a big influence over many people who came after her.”

Always as independent as she could possibly be, Blanche Lazzell lived in Provincetown until her death at the age of 77 in 1956. In her later years, the garden declined, and her beloved wharf studio at 351C Commercial Street, which tragically escaped the attention of local preservationists, was demolished during a renovation by the new owners in 2002. “People in town at the time felt like its destruction somehow slipped through and shouldn’t have happened,” Bakker remembers.

Lazzell lived in Provincetown on her own terms. Even if it wasn’t always easy, it was worth it — a sentiment many residents today would echo. “The thing is to live as simply as possible and do our own work,” she wrote to her sister in 1932 at the age of 54. “That is what I have done all along & that is what hurts my knees. It felt so good when I came back to town. Two yachts are out there with tall sails. The water is always so beautiful, and my work goes on. I have my painting & I am well. That much to be thankful for. Love to all, Blanche.”