Zipporah Potter Atkins was the first Black woman to own a home in Boston. She was born in 1645 to enslaved parents and purchased her house in 1670. LaRissa Rogers, a 2023-2024 visual arts fellow at the Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, has made a two-thirds-scale replica of Atkins’s house, installed on the Rose Kennedy Greenway in Boston through the end of October.

Rogers’s work honors Atkins and her legacy while drawing attention to troubling aspects of African-American history, including the transatlantic slave trade and the more recent displacement of homeowners to build the John F. Fitzgerald Expressway.

Rogers speaks of “spaces of possibility” regarding Atkins’s house. That a 17th-century Black woman in America might own a home seems implausible. But at the time of Atkins’s birth, the law in the Massachusetts Bay Colony declared that children born to slaves were free.

“There was some kind of loophole in the land ownership laws of the day that allowed her to get that land,” says Rogers. Atkins had to know how to read the deed and sign her name. Moreover, she was married twice but remained the sole deed-holder.

The design, materials, and site of Rogers’s public sculpture, titled Going to Ground, echo with poetic and historical significance.

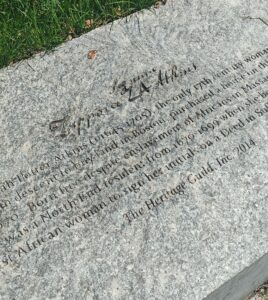

The details of Atkins’s story are recorded in the sculpture’s foundation. Its dimensions, 25 by 29 feet, correspond to Atkins’s age when she purchased the house (25), and the number of years she owned it (29).

Constructed of modular steel, the sculpture is an open structure in the shape of a modest two-story house. Based on renderings from historical records of Atkins’s home, it features rectangular four-pane windows, a solid door, and a chimney.

The roof has a criss-cross pattern through which light and rain pass. In providing only partial relief from the elements, the roof suggests the precarity of home ownership for many. Rogers also intends the design to suggest scars left by lacerations from a whip and the wounds of slavery. The sculpture acts as a sundial: as the sun moves it projects shadows of the scarification on the ground below.

Going to Ground is located at the site of Atkins’s actual home, on a greenway that was once a major highway. To build highways there (once in the 1950s and again in the 1980s), people were displaced from the land, including immigrants and a disproportionate percentage of Black Bostonians. When the “Big Dig” rerouted Interstate 93 underground, the Rose Kennedy Greenway replaced the old John F. Fitzgerald Expressway on the site.

Rogers’s structure stands in the center of the greenway surrounded by a lawn, condominiums, and office buildings. People pass though on walkways, while others sit at the park’s tables, having lunch or reading. Contemporary Boston has been built up around this space and its history. Going to Ground seems to radiate both strength and humbleness, standing in defiance of the larger buildings around it.

The work’s title, a reference to Vanessa Agard-Jones’s call to action by “collectively going to ground,” alludes to the realities of the past and the current housing crisis. It implies the opposite of movement and is a declaration of place as a space of one’s own.

Rogers embraces the tension of these simultaneous readings, which she likens to competing narratives. There are references to the past and the present and also to violence and hope.

“I didn’t want the work to feel like a Band-Aid or highlight one narrative without showing the multiplicity and the totality of reality,” she says.

Rogers went to the ground herself to create the foundation of her sculpture. She used oyster shells collected during her time at the Fine Arts Work Center to create a limestone mixture called tabby, a precursor to concrete.

“I wanted to incorporate that because there’s such a tie to tabby in the enslaved communities, especially on the East Coast,” says Rogers. She was also thinking about a relationship to land not tied to the commodification of labor. “There’s a rich history of freedmen’s towns and Black beaches,” she says. “I wanted to bring in these places of play and joy.”

The foundation is also made of earthen blocks that include soil contributed by members of the Boston community. Rogers hosted an “open call for soil,” asking people to submit soil samples from personally meaningful places, “a communal gesture in open-hearted labor and Black placemaking.” She received more than 100 submissions.

The archival research that brought Atkins’s story to light was conducted by Vivian Johnson, a retired Boston University professor. Rogers first learned about Johnson and Atkins through Audrey Lopez, director and curator of public art at the Greenway Conservancy, whom she met in 2021 in Los Angeles. Soon after that, Rogers started work on Going to Ground, which was officially unveiled in August 2024.

Rogers’s time at FAWC was an important step in helping her realize this project. She was in Boston almost every other week and was able to do site visits and field research. FAWC also gave her time. “Provincetown required me to have a different relationship to myself,” says Rogers. “I experienced a slowness I wasn’t given before. It allowed me to think and be present in a different way. This project required that of me. I didn’t know it at the time, but that’s essentially what the project itself is asking. It’s asking these questions about attention and slowness and repair and effort.”

Going to Ground will be dismantled after Oct. 31. It was intended from the start to be temporary. Rogers and Lopez are working on getting it re-situated and hope it will stay in Massachusetts.

Atkins’s transcendence of limitations is “a beacon of hope,” says Rogers. “That’s how I’m thinking about things now. What is required of us to transcend, to show up and build a community that is not dehumanizing but brings us together? What is required for us to actually hold space together?”

Place of Possibility

The event: LaRissa Rogers’s Going to Ground

The time: On view through Oct. 31

The place: The Rose Kennedy Greenway, Cross St. and Hanover St., Boston

The cost: Free