Duncan Johnson grew up near a dump in Rockport — “a makeshift playground,” he says — where he’d scavenge for treasures. After graduating from the Pratt Institute in 1987, where he “lived and breathed” photography, he moved to Williamsburg, Brooklyn. There he’d hunt for the discarded things other people left behind: scraps of construction material and old furniture. He loved “the randomness of it,” he says. “It all had a story.”

Johnson’s lifelong fascination with scraps and refuse is reflected in his artwork. In Brooklyn, he made sculptures from the objects he found; more recently, he has been constructing two-dimensional images from discarded wood and magazines.

A retrospective of Johnson’s work will be on display at the Jeff Soderbergh Gallery in Wellfleet starting Sept. 13. The works span 35 years and were made in a range of sizes. Despite their gritty origins, these are refined, intricate artworks.

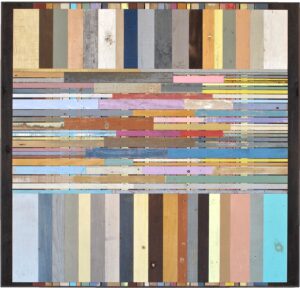

Flow Thru is one of the larger works in the show at 45 by 45 inches. Parallel streams of pastel-colored rectangles run beside and across each other, like intersecting highways of wood. Johnson uses tiny nails and glue to hold the pieces together.

Bravo, much smaller at 16 by 16 inches, is similarly complicated: rectangles, thin and delicate-looking, cross each other in perfectly perpendicular lines. In the foreground, appearing to float above the orderly chaos, is a square of wood — also made of rectangular planks.

Johnson calls himself an artist. “But a lot of times when I’m working,” he says, “it feels much more like engineering.” Part of the narrative of his retrospective, he says, is “an interest in mixing things together and seeing what’s possible.”

In some of Johnson’s works, the wood appears to move or to be positioned in impossible arrangements. Shift, in which diagonal strips create the illusion of a square, is difficult to look at straight on. In Do It Yourself, black-and-white images transferred from newspapers coat the wood so thoroughly that they seem to distort the material; they confuse the eye. Swarm, another eye-catcher, is made from the scales of pine cones.

Johnson’s studio is in a former paper mill in Bellows Falls, Vt. It’s bright with light from the old windows, but other than that, “it’s pretty basic,” says Johnson. The heart of it is a table saw and a small power miter saw. An electric sander, acquired not too long ago, allows him to sand wood to a specific depth — often very thin. He’s invested in sophisticated routers and “all kinds of crazy hand tools,” he says, but those tools mostly go unused. “I like it simple,” he says.

Many of his two-dimensional works have their origins in “a small mountain of wood” he found at a Vermont dump in 2009. Inspired by the wealth of free material, he began to “work on the wall” with reclaimed wood. He cut the wood into rectangles and squares and constructed two-dimensional planes of color and texture, like geometric optical illusions. At the time, he says, “I deliberately called them paintings.” These days, he says, the distinction between painting and sculpture seems less important.

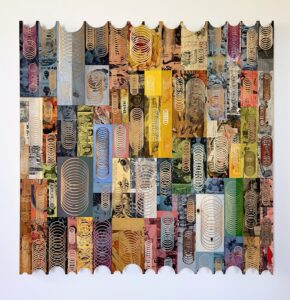

In his studio, he also has piles of images from old magazines. Many of his pieces feature those images, transferred onto the wood. Spring Collection, measuring 38 by 38 inches, is covered with transferred images of faces, bodies, insects, and furniture. The images are camouflaged into the surface, tucked into the woodwork and stained yellow, pink, and blue. Johnson used a drill press to carve circles into the surface, layered like springs. The title might refer to the catalog-esque gathering of people and items into one cacophonous image. Or it might refer to those circles scattered across the piece — all vertical, always meticulously organized despite their seeming confusion.

Johnson is drawn to pieces that are “intricate and deep,” he says. He hangs his work on the walls around him “to soak it in.” There are certain factors he understands will make a piece successful: a certain “magic ratio” of material, color, and size and a slightly effortless feeling, “like they just happened,” he says.

Of course, there’s nothing effortless about the making of these artworks. Each one is created through a labor-intensive process driven by Johnson’s ingenuity and aesthetic vision. Combined in the exact right way, he says, a piece of artwork “clicks.”

“It’s like a good movie,” he says. “You can have great actors and a good script, but if the directing isn’t right, or if the music is bad, it can ruin it. Get everything in just the right balance, and it just works.”

Retrospective

The event: The artwork of Duncan Johnson

The time: Sept. 13 to 27; opening reception, Saturday, Sept. 13, 3 to 7 p.m.

The place: Jeff Soderbergh Gallery, 11B West Main St., Wellfleet

The cost: Free